By David M. Bernstein

Reprinted from Caribbean Life, May 1997

I think Dorothea Lange’s 1932 White Angel Breadline is one of the great photographs in this world. Its power, its beauty, its message, can be understood, felt more valuably, deeply through this principle of Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy founded in 1941 by the American poet and educator Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

The way opposites are one in photography represents the way of seeing people that the world is desperate for now! Art, I learned, answers the question Eli Siegel asked, and answered, with the greatest kindness and exactness: “What does a person deserve by being alive?”

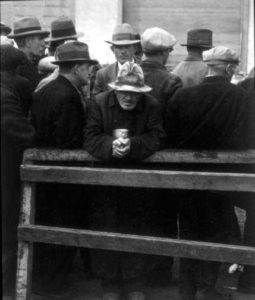

In the midst of the Depression, 14 million people were unemployed. Near Lange’s studio in San Francisco was a breadline set up by a wealthy woman known as the “White Angel.” Looking at this photograph we cannot help but compare 1932 with what is happening now throughout America. Dorothea Lange brings us closer to the feelings of millions of people. As an artist she gave beautiful form to her anger about what people were forced to endure.

In my study of Aesthetic Realism I have learned that every person deserves to be seen aesthetically, as a oneness of opposites; and we can learn how from this photograph. Eli Siegel’s question about Universe and Object from “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?” is at the heart of what makes “White Angel Breadline” so important. He asks:

“UNIVERSE AND OBJECT. Does every work of art have a certain precision about something, a certain concentrated exactness, a quality of particular existence?—and does every work of art, nevertheless, present in some fashion the meaning of the whole universe, something suggestive of wide existence, something that has an unbounded significance beyond the particular?”

The opposites are truly honored in this photograph. The situation is painful and cruel: these men are without work and without food. Yet, what they are deprived of by an unjust economic system, the artist restores to them: their existence has “an unbounded significance”, a meaning for all time. I believe Dorothea Lange had a great emotion, and her technique is as careful as her emotion is large. The solitary figure in the foreground is clasping his hands, almost as if he were praying, and by those hands is an empty cup. His back is to the other men, yet we feel intensely the particular existence of this man alone with his thoughts, as we are aware that he stands for all those behind him, and so many more. Dorothea Lange carefully isolated the man against a dark background with a warm light on his hands, the simple cup, and his hat. She said:

“Sometimes you have an inner sense that you have encompassed the thing generally. You know then that you are not taking anything away from anyone: their privacy, their dignity, their wholeness.”

Before I met Aesthetic Realism, whenever I saw a very poor person, I am sorry to say that rather than having compassion I was angry that I had to think about him at all. I was economically fortunate, and didn’t want to think about other people’s suffering. I used the fact that I was pained in other ways to feel I had a right to be unfeeling both to people I knew and those I didn’t know. The greatest kindness was shown to me in Aesthetic Realism lessons, where Eli Siegel taught me I had to want to know the feelings, including the pain, of other people in order to like myself. In a lesson in 1963, Mr. Siegel said to me:

Eli Siegel: You’ve got this feeling that you’re the only person who suffers. That’s part of the human “special.”

David Bernstein: I’ve felt that.

Eli Siegel: Is it true?

David Bernstein: It’s not true.

Eli Siegel: Are you glad it isn’t true?

David Bernstein: I’m glad.

And Mr. Siegel gave this example:

Eli Siegel: When you can understand your mother at her most lonely and sad day and also most angry day, you will have freedom for yourself. Because we cannot be free until we feel we’re fair to the suffering of others.

This lesson changed my life. And I have seen that what will make a person free is what will make America itself free.

Ms. Lange courageously saved an earlier view taken at a low angle minutes before, where the man seems lost and obscured. In her desire to really see what another person feels, she looked for a more precise way; and in a sense, a more humble way.

Positioning herself higher, and pointing the camera down— something wonderful happens that shows this man more truly and with dignity. He becomes the center of a great triangle. Everything radiates from his clasped hands. While we are looking down, the motion of the photograph is up and out. How different Lange’s purpose is from the purpose people ordinarily have in positioning themselves higher than other people. Lange looked down in order to look up.

The man’s hands are not folded in resignation. There is a feeling of “concentrated exactness” in his gesture which makes for energy and intensity, and there is hope in the composition itself. His hands, cup, and hat are in a progression which joins him to the people behind him in an expanding wave that carries us up and out at the upper right. The stillness in the crowd is given energy by the angles of the wooden rails, pushing out on both sides, while also supporting the man. The rails barricading the men radiate outward — firm beams of light in the dark relate them to the wide universe.

Within the large triangle formed by rails and men, there is an interplay of the triangles of the fedoras with the round shapes of the caps. Fedoras and caps represent opposites too: they are elegant and everyday; both are arrangements of straight lines and curves, and the effect is very pleasing. Still, we constantly return to the central figure. His hat, worn and battered, is also one of the brightest and most lively shapes.

I had the privilege of learning from Eli Siegel in an Aesthetic Realism lesson that the respect I hoped to give as a photographer was also what people, including my wife, deserved from me. He asked:

Eli Siegel: Can you say to Alice, “I’m sure, every fiber of me, every capillary, that having respect for you is just the thing for me”?

David Bernstein: No, I couldn’t.

And Eli Siegel showed that there is nothing respect doesn’t include:

Eli Siegel: It means a color, it means a feather, it means a pebble, it means a bit of dust, it means a lamp, it means a person, too. That is, to respect something is—from the artistic point of view—to see that thing as having the universe in it, and seeing it therefore as making oneself more in an accurate way.

Dorothea Lange shows that respecting every detail makes for great wonder. The folds and creases of their garments have us feel there are real bodies inside them, while we don’t know who these people are. This is very kind. It is a kindness, I have learned, that comes from a beautiful anger — an anger with the coldness and selfishness that make breadlines necessary at all.

The question “What does a person deserve by being a person?” is a national emergency now. Millions of people are homeless now, as in 1932. 1 have learned from Aesthetic Realism that the only way for there to be justice for all is when the economics of America is fair to the aesthetic structure of the world. Dorothea Lange’s photograph is a terrific criticism of the profit system, which is based on selfishness and contempt: the exploitation of people for profit without caring about their feelings or what they deserve. Every good photograph is against the injustice, the ugliness of the profit system, because its purpose is to see objects and people justly, as they are, and in relation to the whole world.

In his book Self and World, Eli Siegel describes so greatly what every nation must go after, and it is the very thing that makes for the beauty in Dorothea Lange’s photograph. He writes: “The purpose of economics or politics is to maintain the collective while intensifying the individual, to support gloriously the universal while heightening properly a specific person.”

Some Resources:

Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning, documentary film

“Women Come to the Front: WW II – Dorothea Lange”- Library of Congress

Dorothea Lange “Migrant Mother Photographs” – Library of Congress