By Carrie Wilson

Reprinted from the Journal of the Print World, Winter 2002

A new exhibition, “The Surprising & Abiding Opposites,” has just opened at the Terrain Gallery, 141 Greene Street in SoHo in Manhattan, with over 40 small and miniature prints, photographs, and paintings by 12 artists, as well as larger prints by Morley, Lichtenstein, Katz and others in the gallery’s permanent collection. The basis of the Terrain Gallery is Aesthetic Realism, the philosophic education founded in 1941 by the great American poet and critic Eli Siegel, and this principle: “In reality opposites are one; art shows this.”

As one of the gallery coordinators, I am proud to quote from our opening statement:

We feel it is crucial at this time for people to know what we are tremendously grateful to have learned: that the world in which terror and death can come swiftly from an airplane, or a piece of mail, is still the world from which all beauty arises. Reality itself is not against us. There is a structure to things that we can count on, respect, take honest pleasure in – the oneness of opposites. This is what all art shows.

At various points in the exhibition we have placed questions from Eli Siegel’s historic Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, and through them gallery visitors see how art takes reality’s opposites—repose and energy, freedom and order, oneness and manyness, sameness and difference—and shows their oneness in new and surprising ways. Art reveals the abiding form within the visual happenings of any moment, whether it is a lively, abstract silkscreen by Larry Zox; a painting of a bunch of radishes by Marcia Rackow; or a photograph by Arnold Perey of a farewell note to “New York’s Bravest” hanging on a chain link fence.

In a recent issue of the international periodical The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, “Terror and Liking the World,” editor Ellen Reiss, writing about our present situation and “the feelings in many Americans of depression, gloom…continuous anxiety,” says:

How our minds fare, how our lives fare, depends on whether we are honestly using ourselves to care for what’s not ourselves, the world….Trying to like the world is the most critical procedure of the human self. It is the desire to see things and people truly, and value them truly.

And art, we learned, is the great opponent of the contempt for reality which Eli Siegel explained not only hurts our minds but is the cause of all human injustice, including wars: “the lessening of what is different from oneself as a means of self-increase as one sees it.” There is a choice we have at every moment between the art way of seeing and contempt. Art is respect for the world.

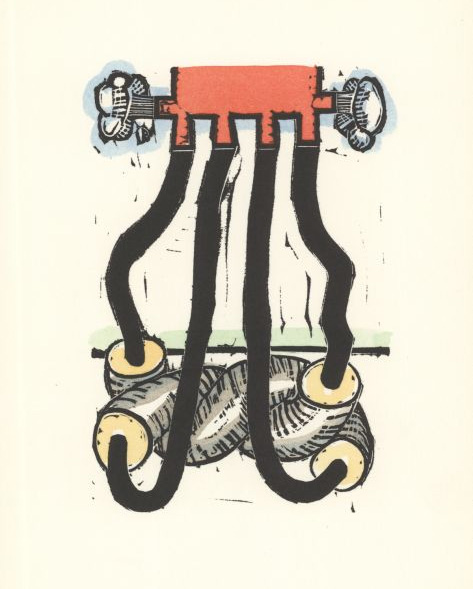

For instance, there are George Nama’s linocuts, beautifully enhanced with watercolor. Nama finds form within the disquieting. In “Air Monument,” a sort of machine with 4 black air hoses like the legs of some strange creature, jiggles in fixity as it lets off steam. Consider it now in the light of Mr. Siegel’s question about Grace and Seriousness:

Is there what is playful, valuably mischievous, unreined and sportive in a work of art?—and is there also what is serious, sincere, thoroughly meaningful, solidly valuable?—and do grace and sportiveness, seriousness and meaningfulness, interplay and meet everywhere in the lines, shapes, figures, relations, and final import of a painting?

In all three Nama works, he gets to a sense of expression and frustration simultaneously—in a valuable and sportive way.

Three works by poet and photographer Louis Dienes show the factual wonder in ordinary household objects—”Doorknobs,” “Cotton Tipped Applicator,” and “Safety Pins.” They arose from an Aesthetic Realism assignment: to write, every day, three sentences about an object, and this is one of Louis Dienes’s sentences:

Here we have safety pins in the box they came in, light glinting on their curving surfaces, pointing every which way, all closed.

Both photograph and words show containment and abandon composed in these objects, as we would like them to be in ourselves. And in the artist’s statement, Louis Dienes quotes from Mr. Siegel’s “Aesthetic Realism and Scientific Method”:

When I ask people to write about objects, it is because I feel that if they honestly try to make sense out of, say, a brush, or a button, or a coat, or a pair of spectacles, that much, by looking at a specific object, they will try to find order in the world. In finding order in the world, they will find it in themselves. That is the only way to find it in themselves.

Also on exhibit is an early silkscreen by Alex Katz, “Luna Park,” a large landscape with two slanting, black trees silhouetted against a lake of gray. Between the thick black leaves we see the round, white moon, and her vertical, curving reflection in the water. There is, in this nighttime scene, stark contrast and yet serenity—opposites we have had to make sense of, as a beautiful September morning had within it sudden, stark change.

“Each time anyone sees something as beautiful,” Mr. Siegel wrote in an issue of The Right Of, “he sees the structure of the world; and it is this structure of the world seen in an object that causes the beauty; is the beauty….Even when we are distressed or confused or humiliated, the world retains that structure present necessarily, inevitably, in everything that is beautiful.” Knowing this can have people stronger, wiser, at this time, and that is the purpose of “The Surprising & Abiding Opposites.”

The exhibition statement concludes: “We have learned from Aesthetic Realism that the lesson of ethics and aesthetics is this: When we give true meaning to what is not ourselves, our selves are larger. The safety of our world depends on people’s knowing this.”

The exhibition runs through February at 141 Greene Street, NYC; (212) 777-4490. The website is TerrainGallery.org.

Carrie Wilson is an Aesthetic Realism consultant and one of the coordinators of the Terrain Gallery.