By Marcia Rackow

As I studied the work of the renowned French Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, whom I care for, I was taken by the energy and motion in it, at one with its form and repose. And I was moved to see how deeply these opposites of energy and repose affected every aspect of her life. I saw that in the very technique of her paintings, she solves a question that has troubled people greatly, as it did me, and the artist herself: restlessness.

In his lecture Mind and Restlessness Eli Siegel described the restlessness I think Berthe Morisot felt, and which I thought I would be driven by all my life. Restlessness, he said is “motion with againstness” with “something compulsory about the motion.” He explained:

The restlessness that is the deepest is the feeling of not being at home in the world that you have been born into. Nearly everybody has that.

I learned from Aesthetic Realism that the great interference with our “being at home in the world” coming from ourselves is the desire for contempt. We cannot feel at home if we hope to see the world and people as beneath us, unworthy of us. When we go against our deepest purpose, to like the world, we have to be ill at ease or restless. And the way we can honestly like this world we are in is by seeing that it is made aesthetically; it is a oneness of opposites. “All beauty,” Mr. Siegel stated, “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

1. “There is extraordinary life and movement, but how is one to render it?” —Berthe Morisot

Berthe Morisot lived from 1841 to 1895. This is a portrait of her by Édouard Manet.

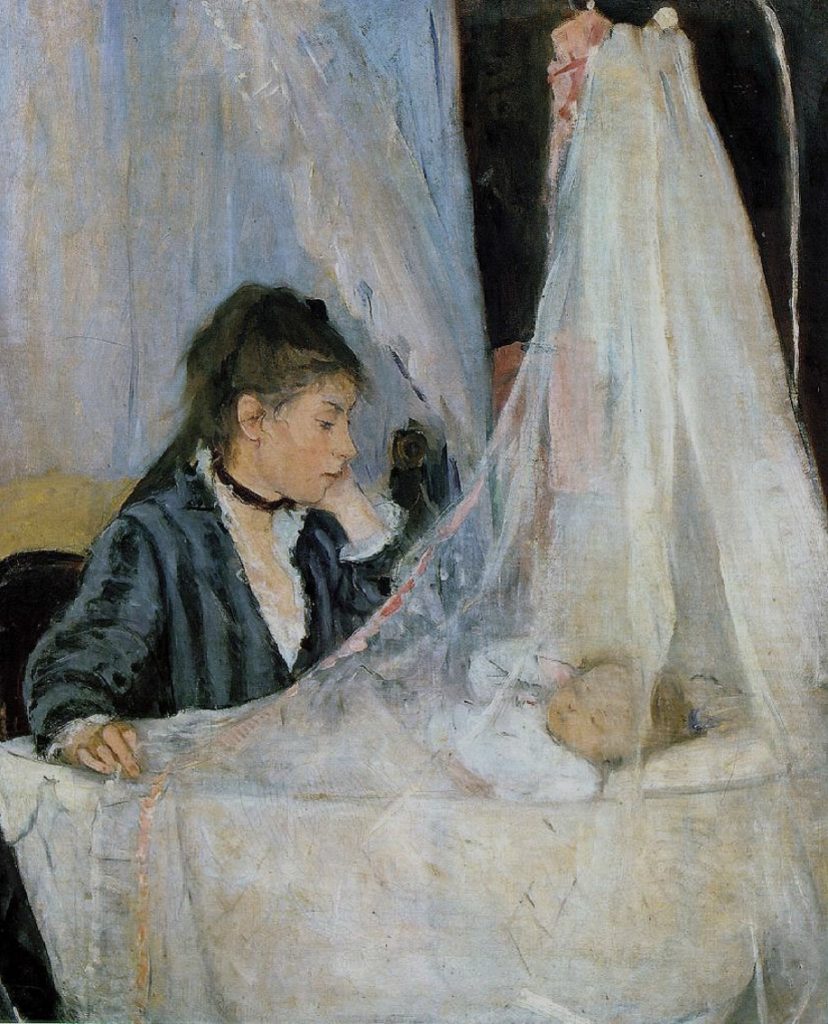

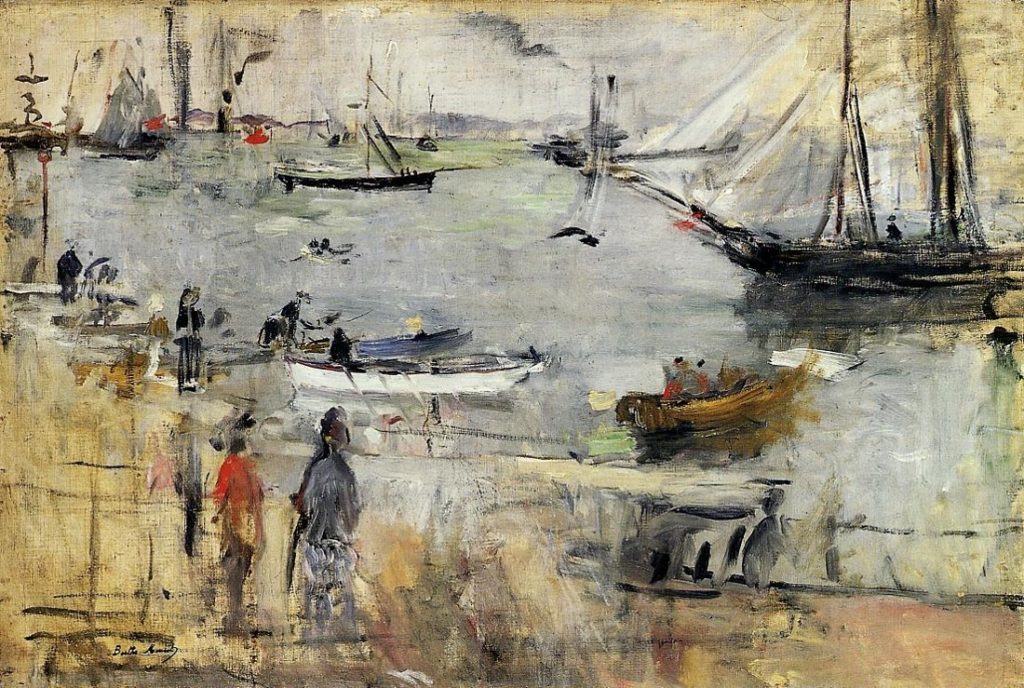

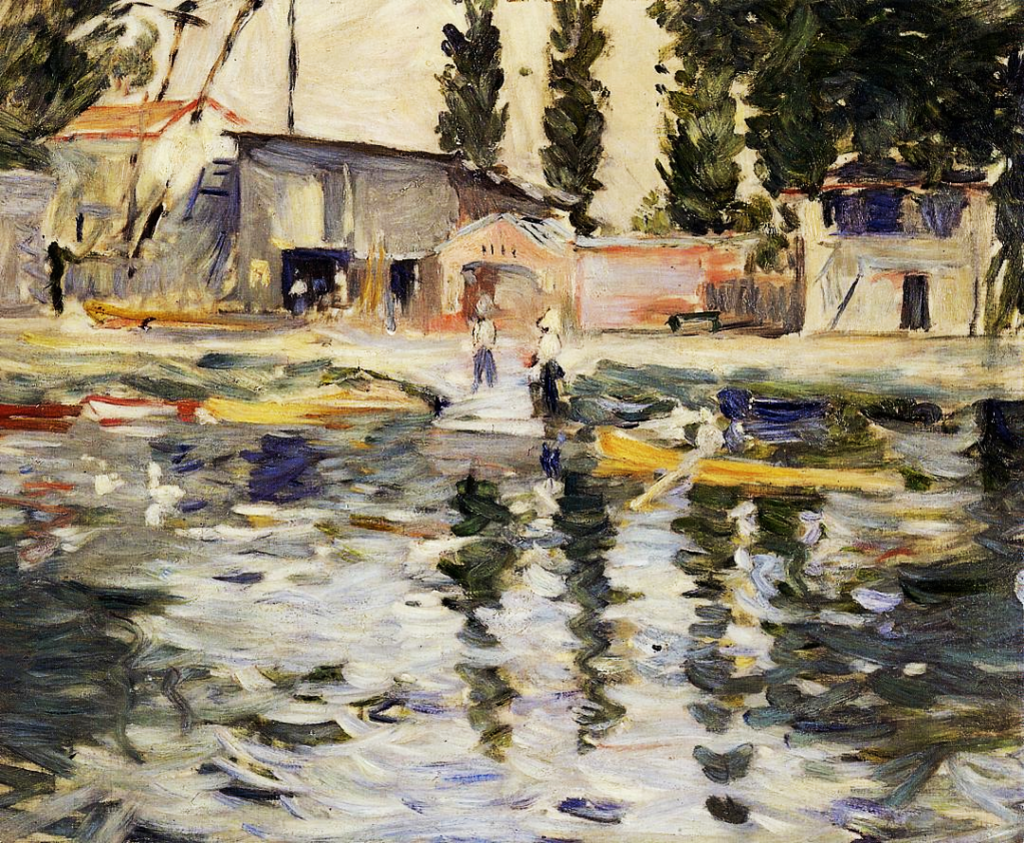

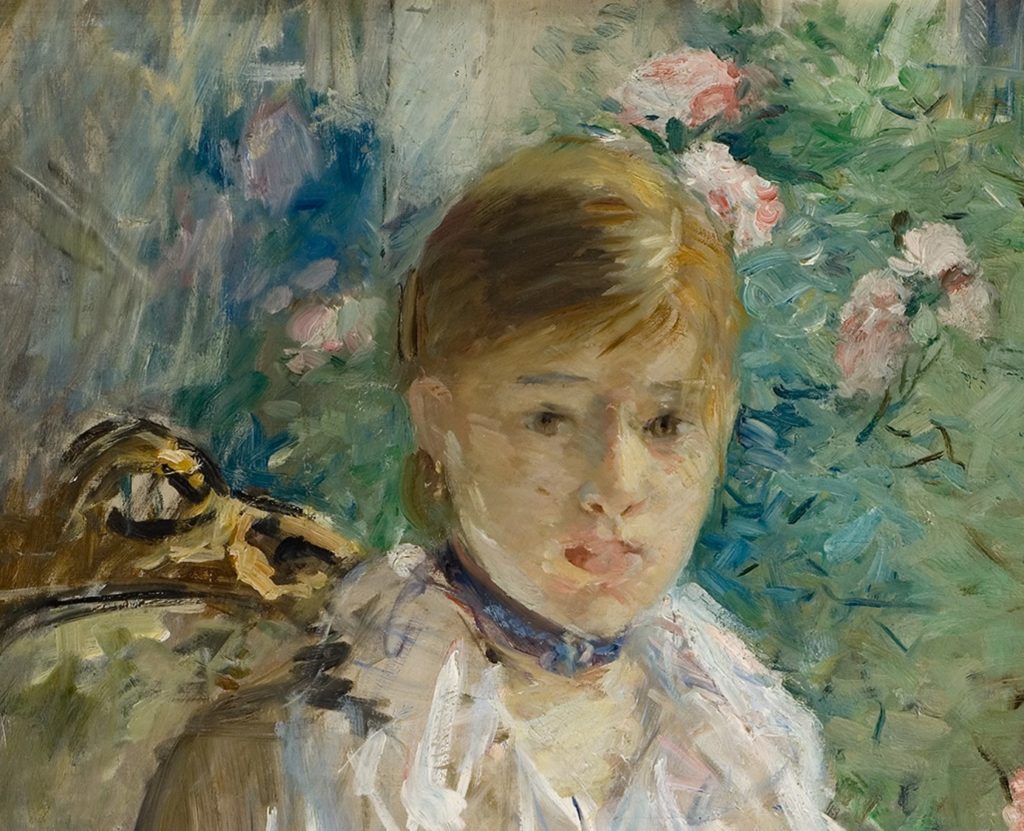

Like every woman, she wanted to be at home in the world, and it was through art that she most successfully met this deep hope. She was courageous in choosing a career as a painter at a time when women did not have careers outside of marriage, and painting was seen as a pleasant accomplishment for cultured young ladies. And she was even bolder in going after the new way of seeing in art that was Impressionism. When the Impressionists first exhibited in 1874, it caused an outrage in Paris. One critic described them as a “group of five or six lunatics, one of whom is a woman.” These are the four paintings Berthe Morisot showed in that landmark exhibition.

The Cradle is one of her best known and loved works. The critic Georges Rivière wrote more accurately,

Berthe Morisot has captured on her canvas the most fugitive notes, with a delicacy and skill and a technique which earn her a place in the forefront of the Impressionist[s].

Another critic, Arthur Baignières, later observed: “Mlle Morisot is such a dedicated Impressionist that she wishes to paint even the motion of inanimate things.”

The artist herself wrote of her love of motion:

People come and go on the jetty, and it is impossible to catch them. It is the same with the boats. There is extraordinary life and movement, but how is one to render it?

In a radio interview in 1963, published in the journal Definition, Eli Siegel described, as no other critic ever had, the essence, the joy, the purpose of the Impressionists, when he said:

The Impressionists saw reality as possibly dancing. Light and color are on a philosophic binge….The Impressionists took up the old philosophic problem of how we can see change and fixity, change and sameness, or motion and rest in an object….The Impressionists were awfully ethical.

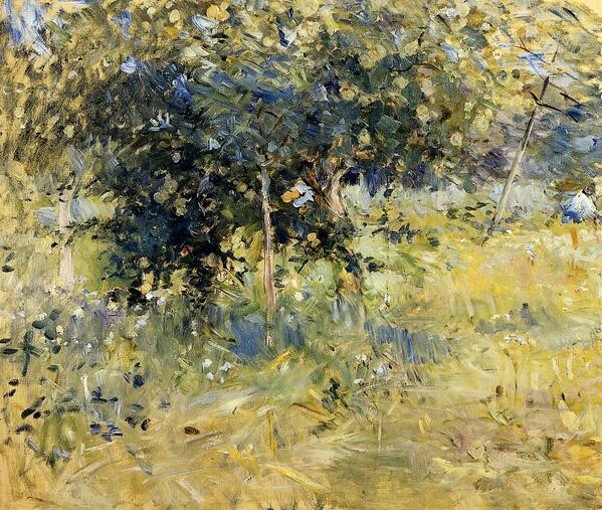

Berthe Morisot “saw reality as possibly dancing,” showed “light and color are on a philosophic binge,” as she painted her family

and friends in the familiar surroundings of her home and garden,

and in the places they visited.

In this painting Young Girl by the Window, of 1878, which I think is one of her most beautiful works, the reflections of light on the white ruffles of her dress are dazzling..

The young woman has an expression that is intense.  There are fixity and attention as she looks directly out at the painter, and at us, and yet we feel there’s something inward in her gaze, and also a feeling she is about to move, that her attention is about to shift elsewhere, as fleetingly as the light.

There are fixity and attention as she looks directly out at the painter, and at us, and yet we feel there’s something inward in her gaze, and also a feeling she is about to move, that her attention is about to shift elsewhere, as fleetingly as the light.

In her art at its best, Berthe Morisot put together rest and motion beautifully, daringly, in a way every person, including the artist herself, could learn from.

She was a very active woman. She painted all her life and worked hard with her colleagues organizing the eight Impressionist exhibitions from 1874 to 1888, trying to have their work known. Although she spent most of her time in Paris, only taking occasional trips to England and Italy to paint, she didn’t feel at home in the world. One of her biographers, Jean Dominque Rey, writes: “A woman with deep feelings, all her life she was restless and often sad, as we can infer from a few brief words in a letter or a notebook.”

We can see this in her courageous Self-Portrait of 1885.

Throughout her letters in her published Correspondence there is a current of discontent and dissatisfaction—what she called “my mania for lamentation.” “The deepest kind of restlessness,” Mr. Siegel explained,

is what we don’t know about. It’s what goes on without outward manifestation. If a person doesn’t like things sufficiently, that person that much is restless.

A keen observer, the poet, Paul Valéry, who was her nephew, wrote:

As for her personal character, it is well known that it was rare and reserved; distinction was of her essence; she could be unaffectedly and dangerously silent and create without knowing it a baffling distance between herself and all who approached her, unless they were among the first artists of her time.

I think that in those words “dangerously silent” Valery is implying there was superiority and snobbishness in that reserve and distance she kept from people. These are forms of contempt that made Berthe Morisot dissatisfied with herself, restless. Art is never snobbish or aloof. But artists can be. In a class Mr. Siegel asked me: “What has been the big mistake of all artists? I said, “To use art against life.” And he asked, “Do you feel you divided the world into two classes—persons aesthetically sensitive and those who are not?”

I had, and my unjust attitude to people also affected my work, making it often flat. And I think Berthe Morisot’s way of seeing people, also affected her work. Where it is least successful, as in this work,

there is an excess motion without sufficient point or fixity that creates something like a veil, a distance around people and objects.There was a fight in Mlle Morisot between wanting to observe the world and people accurately, be affected by them, paint what she saw, and feeling she was more herself being superior—”creating a baffling distance between herself and all who approached her.”

2. Why I Was So Restless

As a young girl, the only girl living in a house with my parents, brother, grandparents, and two uncles, I was made a great deal of. I used the praise I got, particularly from my father, who was a commercial artist, to feel I was a little princess, and I was disdainful of other people.

But, I saw no relation between my assumed superiority and self-satisfaction and the agitation I felt increasingly. I was a person constantly on the move, scattered; I felt like a nomad, frantically looking for a place I could call home. After college, I could not stay in one place for more than a year, and for the next ten years went back and forth from New York to Italy, with a year in between in San Francisco. Once, a friend drew a picture of what he saw as my life: it was a series of sparklers going up in the air and fizzling out.

In the lecture I’ve been quoting, Mr. Siegel said:

Many persons have tried to annul dissatisfaction with oneself by being in motion and going places. Restlessness is a phase of the feverishness of guilt.

I did feel a pervasive sense of guilt and was constantly apologizing to people, even for things I didn’t do—like having my toe stepped on, on the subway. Although I was troubled by this feeling, I had no idea what it came from.

However, with all my apologizing, as I lived in different places and made many acquaintances, I had a secret pride and even arrogance in feeling I could pick up and leave any time I pleased. I wasn’t going to get tied down to anyone or anything. Meanwhile, by the time I returned to New York once again, I knew another change of place wouldn’t change my life—something in me had to be different, but I didn’t know what it was, and all the psychology and philosophy books I read didn’t help. Finally, I met the knowledge and the comprehension of myself I was looking for!

In the first Aesthetic Realism class I attended, Mr. Siegel asked me, “Do you think your highpoint in life has been the evasion of liking something?” “Yes,” I said. And he asked: “Do you think it is a mode of true triumph?” “No, I don’t,” I answered.

I began to see that I had gone on the premise that it was—and that this was the very reason I was so unsure, and so “feverish” that I had to be constantly on the move. And I learned that my contempt was completely opposed to my purpose in painting. Mr. Siegel asked me: “As artist, do you think every time you are working at something your purpose is to make the world look better?” It was. Respect for what is outside of us, which is the purpose of art, has a person feel at ease in the world—composed and in motion at once. I was learning how to have this same purpose in my life. As I saw that the opposites that make for beauty in art, are in every person and thing around us, I began to see the world newly. I saw people, including my family, as interesting, worth knowing and felt at last I was in the right world, one I could honestly like.

That I feel at home in the world and can be useful in the work I cherish as an Aesthetic Realism consultant and art teacher, is a source of unbounded gratitude, as is the fact that I have true love in my life in my happy and ever-deepening marriage to Ken Kimmelman, filmmaker and consultant. I love and respect Eli Siegel and Aesthetic Realism for making these profound changes in my life possible!

3. “We can go away from the true thing in ourselves, but we will always be homesick for it.” —Eli Siegel

Berthe Morisot was born in Bourges, France and grew up in Paris. Though her family was of the comfortable bourgeoisie, they did encourage her study of art. When Berthe was 16 she and her two sisters were given painting lessons. But she soon became dissatisfied with the academic training they were receiving, and began to study with the noted landscape painter, Camille Corot, who became a regular visitor to their home. At this time, she also met the painter Édouard Manet. Though I cannot adequately comment here on her feeling for Manet, I think he is the man and artist she respected and cared for more than any other man she knew. And it seems he had a deep care and respect for her. She sat for many of his paintings and he encouraged her art. These are some of the beautiful paintings he did of her.

And it was at the home of Manet’s parents that she met some of the other leading artists and writers of her time: Baudelaire, Degas, Zola, Mallarmé.

But the young woman, who her brother Tiburce said, “devoted herself with feverish zest to her work,” who could be so eager to go out into the countryside, “pursuing one motif after another, ”

could also be bored and disdainful of everything. There was in Berthe Morisot, as in many woman, myself included, another hope, another motion—away from the world and disproportionately towards herself. In a letter to her mother, she complained:

The only thing I see again is rain coming down in torrents. I drag myself about aimlessly, and I say twenty times a day that I am tired of everything. That is how my life goes. I am ashamed of being so weak-minded but what can I do?

Mr. Siegel explained:

Restlessness is painful because any division of mind is painful. Restlessness is the dramatic sign of division of mind….We can go away from the true thing in ourselves, but we will always be homesick for it.

In a class Mr. Siegel gave form to and explained this “division of mind” that made for the hurtful relation of rest and motion in my life, and he showed it is a question of art. He said, “There are two opposites picturesquely described as swirl and tidiness.” And he asked, “Do you believe so far you’ve trusted yourself more with swirl than tidiness?” “Yes,” I said, and felt that in this question Mr. Siegel was describing something that affected me throughout my whole life. Though as artist I was interested in objects and tried to be exact as I painted them, in my everyday life I was careless. I had seen my fluttery manner as part of my artistic personality, my charm—but it wasn’t really charming at all. It was contempt. Mr. Siegel said:

The big problem of everyone is being tidy and wandering. Every painting, every dance, every photograph, every film has this deep question of self: Should the self stay put or be everywhere?

Mr. Siegel understood and explained this pervasive question of my life, and enabled me to change.

“Should the self stay put or be everywhere?” is a deep question that took a particular form in Berthe Morisot’s life, and it affected me to see how the opposites Mr. Siegel described as “swirl and tidiness” are almost a literal description of what we see in her work.

In this dazzling painting, Lady at Her Toilette, of 1880, a woman in white is seated before a mirror with her back to us, and around her there is a swirl of color.

Although this is an interior, there is a sense of light and space, sky and flowers in the cool, flickering blues and greens, and in the flashes of yellow and pink and mauve surrounding her.

Her back is beautiful. She is sitting upright, rather proudly, while her head is slightly bowed, and we feel something compact, tidy, in the strong vertical line of her body.

It is surprising that Berthe Morisot does not show the woman’s reflection in the mirror, and I think her choice is important.

Commenting on a situation in literature where a person’s face is not seen, Mr. Siegel wrote, “The desire for the sight of the face…becomes more and more like our desire for the unknown in us, which is ourselves, and yet seems everywhere.”

Commenting on a situation in literature where a person’s face is not seen, Mr. Siegel wrote, “The desire for the sight of the face…becomes more and more like our desire for the unknown in us, which is ourselves, and yet seems everywhere.”

I think the artist was trying to show the self as everywhere in the way she shows the objects reflected in the mirror, but not the woman’s face.

I think the artist was trying to show the self as everywhere in the way she shows the objects reflected in the mirror, but not the woman’s face.

The artist has carefully delineated certain forms—the edges of the woman’s arm, the curve of her neck, the black ribbon around it, the point of her chin, and the blue ribbon along her dress which make for a feeling of tidiness.

And then she has allowed the swift, energetic brushstrokes to blend into each other, blurring the edges of the forms,

showing matter is in space and light, and that space and light have color and substance. It is beautiful. The swirling colors of the background seem to coalesce into the forms of the woman—and the woman seems to go out, expand, become part of everything around her. She stays put and is everywhere at once.

4. Art and Marriage—& What a Woman Is Learning in Consultations

In 1874, the year of the first Impressionist exhibition, Berthe Morisot married Eugène Manet, the younger brother of Édouard. She was 33 at the time, and though she had had many admirers and suitors, she had not been eager to marry. Marriage, I have learned, is a study in the very same opposites which Mr. Siegel showed are at the center of Impressionism—change and fixity, motion and rest. Because she didn’t feel that she was more in motion, changed, freer, and at the same time more herself knowing a man deeply and being known by him, there was pain and restlessness in her marriage to Eugène Manet.

Yet as artist she did try to see–-to know who her husband was. These are paintings of Eugène—in the park with their daughter Julie

in the garden with Julie

and this more penetrating study of her husband done a year after their marriage, titled Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight.

Had she known that in the very structure and purpose of her work was the way of seeing her husband she needed, I think her life and marriage would have been happier.

This is what painter Olivia Raeburn was fortunate to be learning in consultations about the restlessness she felt. Mrs. Raeburn, a very independent woman, had an interesting career, travelled in Europe where she had various commissions for paintings, and said she hadn’t seen herself as getting married. Then she told us about first meeting her husband, Matthew, a physicist, much absorbed in his work: “He melted on the spot,” she said. “His eyes had a penetrating look of intelligence. Of course, he fell in love instantly.” But with this victorious reminiscence, she showed a wistfulness—the sense of some meaning not found. We asked her: “Was Matthew’s ‘melting on the spot’ a triumph for you?”

OR: I was amused.

C: Were you haughty? Weren’t you deeply affected? Women are interested in a man who praises them—the faults grow dim as the praise increases. Was your “amused” reaction called for?

Olivia Raeburn paused and said, “I wanted to be free.”

C: Did you have contempt for Matthew Raeburn? You have seen the restlessness in your marriage as Matthew’s fault. Do you think you had such scorn for him that it drove him into himself?

We knew Olivia Raeburn needed to see her husband in relation to the whole world, not only to herself, and we wanted her married life and her artistic life to blend well, to help each other. And so, in one consultation we looked at this painting Berthe Morisot had done of her husband. We asked. “What is the most noticeable thing in this painting in terms of composition?”

OR: Well, the strong horizontals and the strong verticals.

C: Who has the verticals?

OR: The man, the woman, the child and the curtain.

C: Right. Does that mean they are all related?

OR: Yes.

C: Now what about the horizontals?

OR: There is the window, the fence, and the window sill.

C: What else?

OR: His gaze?

C: Is there something else? We’ll give you a hint. It starts with “c” in French–“chapeau.”

OR: Oh, the hat

C: How does that continue the horizontal?

OR: It just does by virtue of being there.C: What is the noticeable thing about the edge of the window and his hat? This horizontal line on the man’s hat continues and also changes from the horizontal of the window edge. Do you think you missed seeing this relation between the man and the window because you have tried to keep the world and your husband separate in your mind?

OR: That’s quite possible. Yes,…then, in other words, what you are trying to tell me is that the relationship made here I have to make with my husband?

C: That’s it!

OR: Oh, that’s what I’d love to do, but how can I?

C: By changing your purpose—criticizing your contempt and going for respect. An artist has respect when he or she shows a person in relation to the world. The highest respect is to see the world in a person and a person in relation to the world. We want you to do that with your husband. We suggest you do a painting of Matthew Raeburn sitting near a window, and tell him that you would like to paint him as a means of having respect for him and curbing your desire for contempt. Can you do that?

OR: I’ll try.

This was a turning point for her. At her next consultation she brought in her painting of her husband, and it was one of the best things she had ever done; there were factuality and solidity in it. She told us she really tried to see what was there. Olivia Raeburn, who had seen her husband, her son, and the people and objects around her in a hazy way, was now beginning to see they are in the real world, and that it is a world she wants to be fair to and can really like.

She represents the tremendous success of the Aesthetic Realism education that can be in the lives of people everywhere.