By Marcia Rackow

Originally presented as part of an Aesthetic Realism public seminar.

What makes Claude Monet’s work so beautiful, and why it has affected people all these years, is explained by this principle stated by Eli Siegel, founder of Aesthetic Realism: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

In a landmark radio interview, Eli Siegel described the great new thing Monet accomplished, when he said:

Monet made the vague, the uncertain, the trembling triumphant. We have a tendency to give edges and tidiness to reality when, it could be felt, reality says: “I am not that tidy, and I don’t have those glaring edges.”

Mr. Siegel continued: “So Monet wanted to see what happened at noon,

and what happened at twilight;

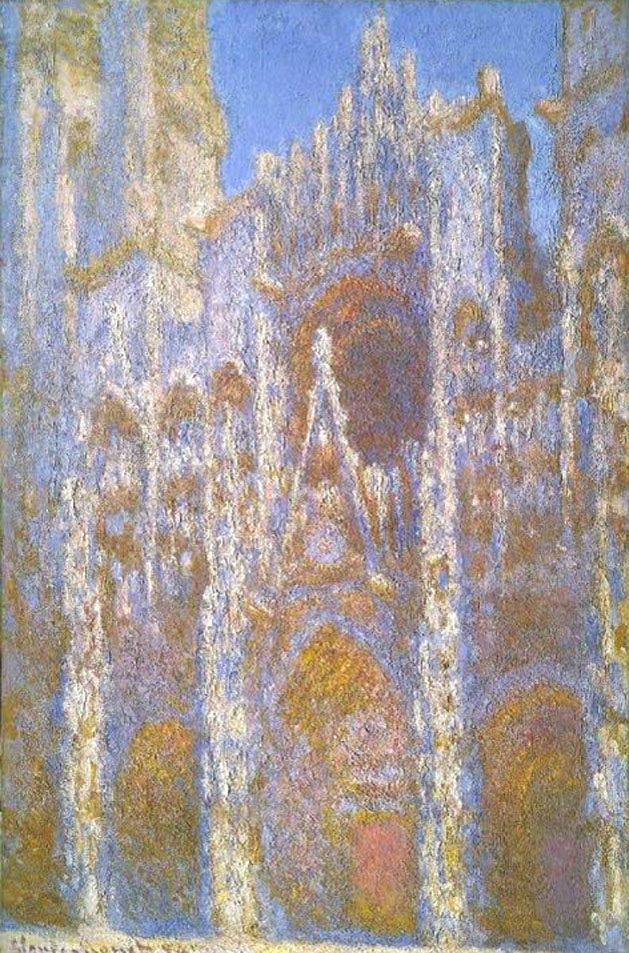

he wanted to see even stone as trembling,

and a cathedral dancing delicately,

and light persisting even as it changed.”

The vague and definite, the uncertain and tidy, the persistent and changing are tremendous opposites in every person’s life, and they certainly have been in mine. While I could be stubborn and fixed in my ideas, I was also very changeable and tentative, adapting myself, somewhat like a chameleon, to every situation.

Early in my study of Aesthetic Realism, my consultants observed, “You have a tendency to slip from one mood to another, a little like the fog. Do you think it’s important for you to be definite?” I had liked being elusive because I felt it made me free, more of an individual, and that I could hide in vagueness.

This was not what I felt when I was painting—concentrating on an object and trying to get it down on a canvas. At those times, I felt things looked vivid to me. Once, when I was doing a cityscape from my apartment window, I remember asking myself, “Why can’t I feel like this all the time?” Through Aesthetic Realism I learned that I had two different purposes that fought in me. As artist I was trying to respect the world, see how it was made. But in my everyday life I generally saw things as unworthy of my close attention and felt I was made of finer stuff. This contemptuous way of seeing interfered with my ability to have the feelings I hoped for, and also with my work as a painter. For example, in my drawings I had a very facile line, an ability to capture an image quickly, but these drawings didn’t show the depth or weight of the object. My consultants explained:

Clarity offends you; your style is vaporous. In your drawings you try to combat the vaporousness by the use of your clear line. But do you feel that your work might lack something because you prefer to hide?

MR: Yes, I’m beginning to see that!

And they asked:

Are you hoping very much to put together the vague and the crisp, the elusive and the definite, the wispy and the sharp in a way of which you can be proud?

When I saw that yes, in my drawings and paintings I was trying to answer one of the biggest questions of my life, I felt such wonder and relief!

The work of Claude Monet affects me—as it does people everywhere—because of the magnificent way he deals with these same opposites that were warring in me. Monet didn’t use the vague to hide, but to show the beauty of reality.

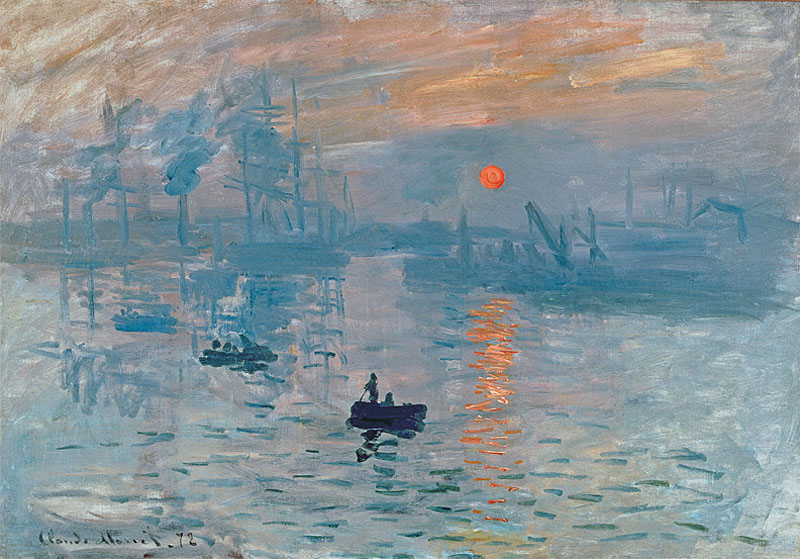

For instance, in this painting, “Impression: Sunrise” of 1872, which gave Impressionism its name, Monet, as Mr. Siegel said, “made…the uncertain, the trembling triumphant.”

In this early morning scene of Le Havre, pale blues, pinks, lavenders, and oranges sweep across the canvas as we see that definite orange sun rising out of a purplish mist, illuminating the breadth of the sky with its pale orange light.

Monet not only captured the rippling surface of the water, but also its luminous depths. Massive industrial smokestacks and rigging in pale blues and lavenders take on the lightness, the fluidity of water and smoke. In the foreground, he has placed the intense dark silhouette of a boat with two men in it—dramatically countering the intensity of the sun, but not overpowering its loveliness. Instead it gives weight, fixity to the picture.

Within all this mist, vagueness, uncertainty, there is a subtle geometric structure underlying the composition. The broad horizontal band of blues across the center of the painting anchors it and gives it a firm base. Then there are the vertical reflections of the sun, smokestacks, and masts going across the canvas, punctuating this misty scene and forming a delicate structure within the water and softly clouded sky. Monet made the “trembling triumphant,” yet we don’t feel we’ve lost our footing because of the way the definite and vague are beautifully made one.

I. A New Vision in Art

Claude Monet’s courage, his determination, his passion to see the world newly, honestly, was revolutionary—as he led the Impressionist movement. In 1895, his friend and biographer, the statesman George Clemenceau, wrote:

Monet’s prophetic eye scans the future and guides our visual evolution, rendering our perceptions of the universe more penetrating and subtle than before.

Monet said about himself that his ambition was to paint “directly from nature, seeking to convey my impressions of her most elusive effects.” And he worked in all kinds of weather—in sun, rain, snow, mist—changing canvases according to the changing effects of the light. He wanted to make the elusive stay put on a canvas while maintaining its wonder. [Click on images for larger size]

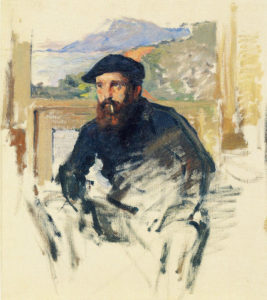

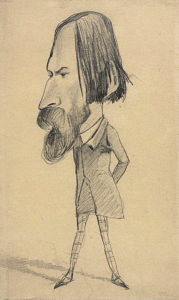

Born in Paris in 1840, Claude Monet grew up in the seaport of Le Havre. He loved drawing and was so accomplished at caricatures that by the time he was 16 he was selling them at a local frame shop. There he met the esteemed landscape painter Eugène Boudin, who, Monet said, opened his eyes “to nature, and I learned to love her passionately.”

He then went to Paris, where he became one of the avant-garde painters and writers of the day—Zola, Courbet, Manet, Renoir, Degas, Cézanne, Pissarro, among others.

At the Salon of 1866 this painting of his future wife, Camille, Woman in a Green Dress, received much acclaim.

But by 1870, when his paintings became brighter and freer, his work and that of his colleagues was vehemently rejected by the Salon. According to their stultifying rules, painting should be of lofty subjects, emphasizing form, line, clarity. Their rejection left the young painters with no way of exhibiting their work, and eventually led to the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.

What they showed on canvas went along with the latest discoveries in science, and new thought in philosophy, literature, and music. But the critics were outraged and brutal in their attacks. The head of the French Academy of Fine Arts called them “a gang of lunatics.” Meanwhile, Renoir said passionately, “Without him, without my dear Monet, who gave us all courage, we would have capitulated.”

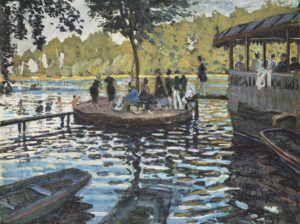

For the next 10 years Monet had to depend mainly on his friends and art dealer to support his wife and two young sons. Yet, in spite of this, he was driven to pursue his art with astounding energy and enthusiasm. He painted “modern life” in Paris—

—life in the country—

and traveled for months at a time to capture the unique light and atmospheric effects he found in the villages along the Seine—

(This is Edouard Manet’s picture of Monet and his wife on his painting boat)

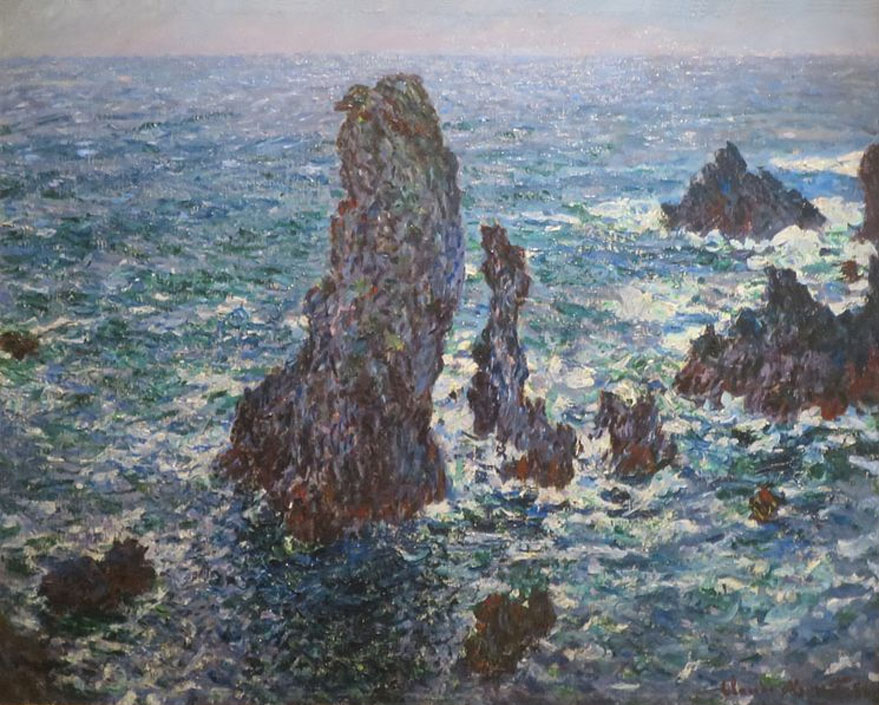

—and along the Normandy and Brittany coasts.

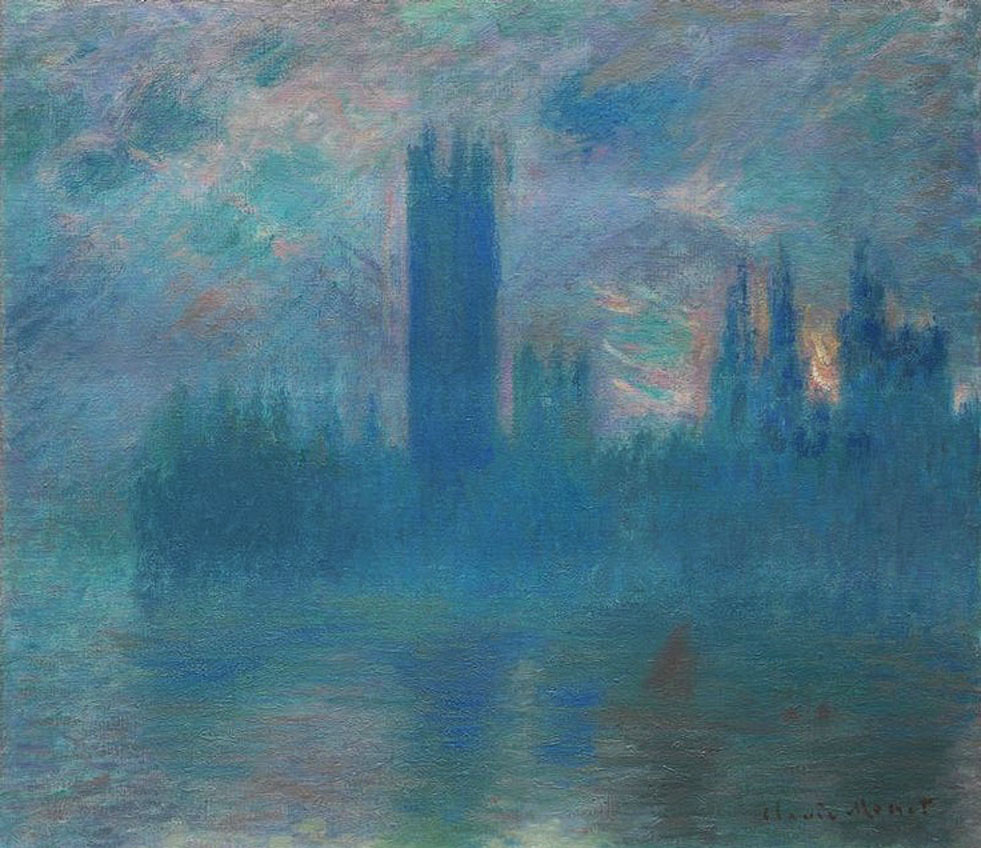

He also loved the London fog,

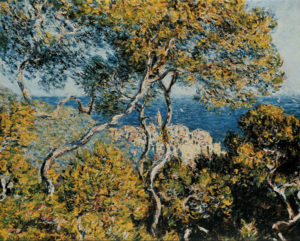

and the Mediterranean sun.

“I have seen him,” said the writer Guy de Maupassant, “capture a glistening shaft of light on a white cliff, and fix it in a rush of yellow tone which made the effect of its elusive dazzlement strangely blinding and unsettling.”

Though he suffered a terrible loss—the death of his young wife in 1879—he kept true to the new way of seeing and painting called Impressionism, and eventually his work began to sell.

Click here to continue to Part 2: “The Message of Art for Our Lives”