By Dorothy Koppelman

I learned this from Eli Siegel in an Aesthetic Realism lesson, and it is written down in capital letters in my notes: THE BIGGEST SUCCESS—THAT WE LIKE THE WORLD THROUGH KNOWING IT.

I learned that the only way to like the world honestly is to see it as a oneness of opposites; and further, that seeing it this way is the means to honestly liking yourself. The more I study this Aesthetic Realism principle stated by Mr. Siegel, the more I am thrilled at its truth: “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.”

I shall be talking tonight about my life, what a woman learned in Aesthetic Realism consultations and about the famous 20th century American artist whose works, as one critic put it, “embody the supreme level of pictorial ambition.”

I. Two Ambitions—One True and One False

Jackson Pollock early wanted to be a painter, and as artist he welcomed challenges, set himself new problems. He wanted a non-smooth life, drove in his old Ford across the country, went into the deserts, over the hills, welcomed the seeming impediments of a three-dimensional world as a means of freedom; he wanted to put opposites together.

Jackson Pollock’s famous action paintings exemplify his true ambition—to like this world—and they are a thrilling sight of a man loving the way weight and lightness, thickness and airiness, impediment and release are one in reality, and showing them in tangible paint handled with a knowing technique.

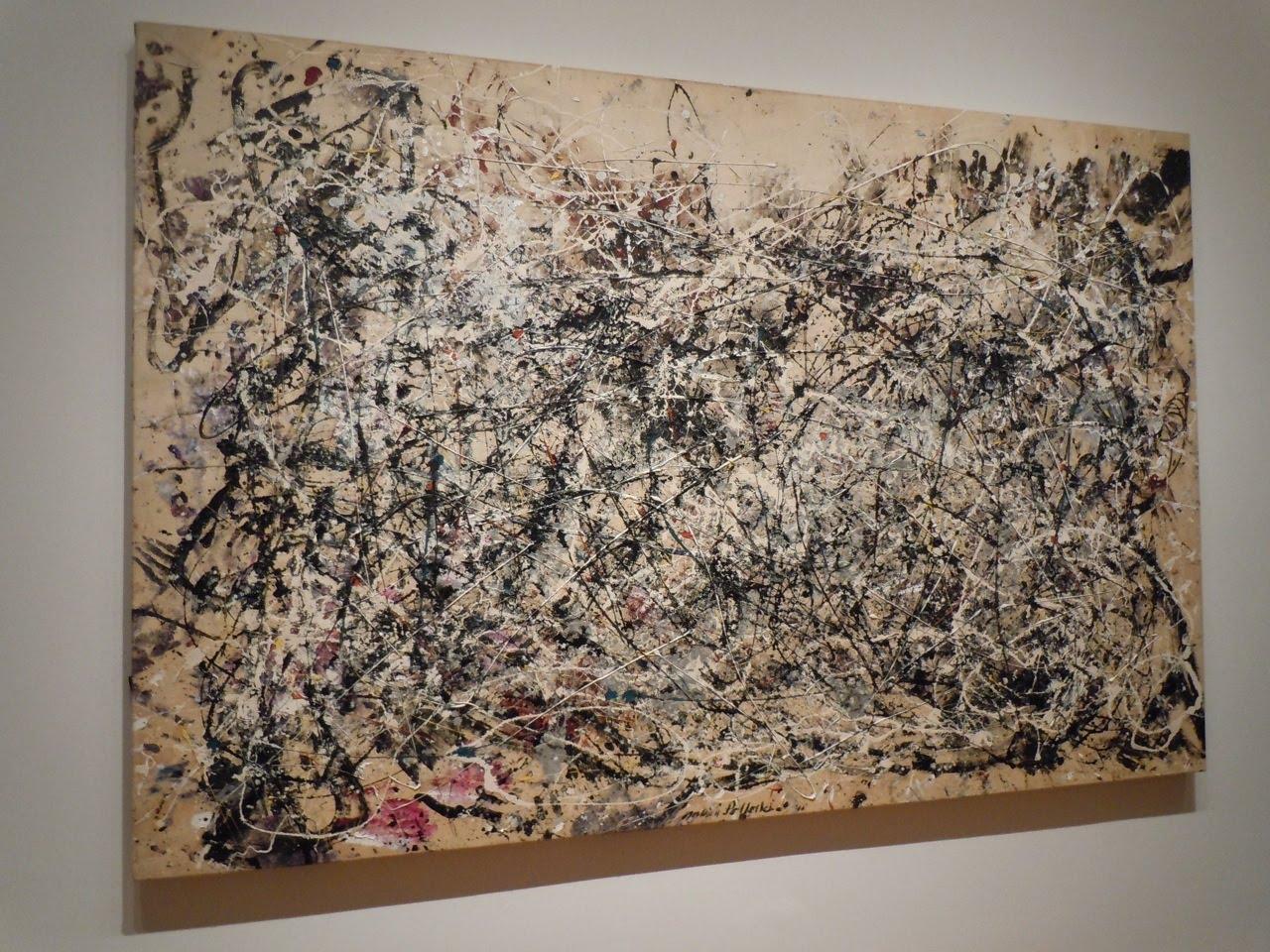

In Number 28, 1950 there is such a careless grace, a feeling of inevitability, a weaving in and out of those thick and thin black lines over a deep galaxy of silver and blue space.

What gives us such a lift are those solid, well placed, low and thick obstructions. But they don’t hold us down! There is a whirling, wild sense of freedom here, and at the same a most cunning arrangement of space as to line, thick as to thin, rise as to fall, abrupt angle and surprising dash. Here, impediment is a means of freedom, and the artist’s beautiful, central ambition is satisfied, and we are satisfied. We feel we can be ambitious to be free like that. It is a sign, as Eli Siegel has described, of the world itself making beautiful sense, and we like it.

But Pollock also went after contempt—he was surly as a child, and felt the way to be free was angrily to get rid of interferences, just annihilate things. How much did that swooping desire to get rid of a reality he saw as impeding him lead to his early drinking, which was to ruin his life?

This is a letter written as an 18 year old which shows both his true ambition, and how contempt was hurting him:

I shall be an Artist of some kind. If nothing else I shall always study the Arts. People have always bored me….I have been within my own shell and have not accomplished anything materially. In fact, to talk in a group I was so frightened I could not think logically….

II. Our True Ambition—to Put Opposites Together in Ourselves

In December of 1955, Mr. Siegel wrote the definitive essay, “Beauty—and Jackson Pollock, Too” which placed the artist in the tradition of painting, with a beautiful respect for the deepest ambition of a person. Mr. Siegel said about Pollock:

The unconscious, as artistic, goes after unrestraint, but unrestraint as accurate; and when unrestraint is accurate, the effect on mind is still that of beauty. And:—if his work is successful, there is in this work, power and calm, intensity and rightness, unrestraint and accuracy—and these, felt at once, make for beauty.

This is Autumn Rhythm with “intensity and rightness” —

And here is a detail:

In Number 1A, 1948, with its joyous “unrestraint and accuracy’ we see the ambition of ourselves given visual, beautiful form:

But the sad separation of opposites in Pollock can be seen in this description by a friend:

He had relatively few interests. He saw things as having no real connection with one another.

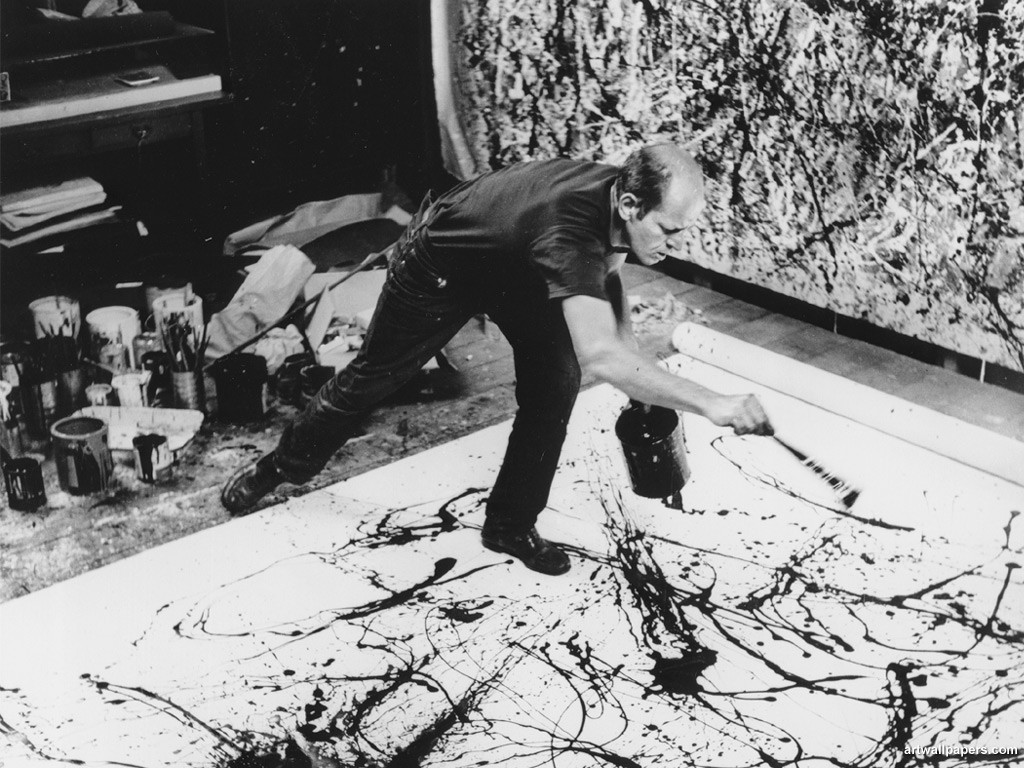

However, a fellow painter described the artist as he worked, “Pollock danced some of the most beautiful paintings in the world.” In this photograph we see that action which made for the name “action painting”:

♦ ♦ ♦

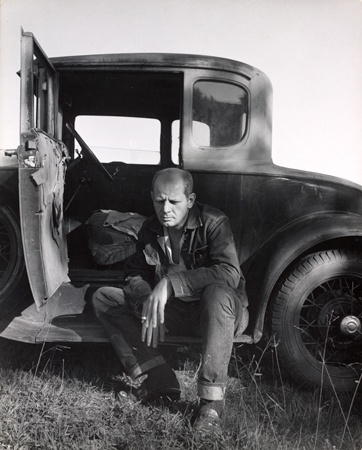

This is a 1955 photograph taken by his friend Hans Namuth of Pollock in the famous Pollock Ford. His brow is furrowed, his long fingers somewhat limp.

As he himself said, “The problem isn’t painting, its what to do when you aren’t painting.”

And Jackson Pollock too often used his important hands to hit people. Once, when a fellow artist hit him back, Pollock, smiled and said “Thank you, but not so hard, not so hard.” I think he was desperate to have someone honestly criticize him.

III. Aesthetic Realism Consultations; or, Her Ambition Was Understood

I am very grateful—and that gratitude increases each year of my marriage to my husband, Chaim Koppelman, fellow student of Aesthetic Realism, fellow artist, and fellow consultant. We learned from Eli Siegel in Aesthetic Realism lessons that the purpose of marriage was to use one another to like the whole world—and learning that made us closer, kinder. Now we are so glad to teach men and women what we know will meet their hopes: the only purpose adequate to the deepest ambition of the whole self is to like the world through knowing it.

In her first Aesthetic Realism consultation Jean Hartman said she knew she really shouldn’t complain. “My husband adores me,” she said, “his business is very successful; I have a beautiful home, three beautiful children.” She said in a bored way that she could buy anything she wanted, and her husband was planning a trip to Hong Kong to celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary. Meanwhile, she didn’t feel good, and recently she found that at home during the day, she sort of lost touch with things.

Consultants. We will ask you the beginning Aesthetic Realism question: What do you have most against yourself?

Jean Hartman. I’m frustrated. I used to be content, but now nothing seems to satisfy me. I used to be more interested in the world. I was an avid reader, but these days I can’t concentrate. One thing I do enjoy is shopping—but you can’t do that forever either.

Consultants. Why do you think you don’t see enough meaning in things now?

Jean Hartman. I don’t even try to. I’m tired. By 4:30 I’m ready to stretch out.

We told Mrs. Hartman that we thought she was exhausted because she was going against her deepest ambition—to know the world—and instead, went after owning things without respect for the world they come from. She was very much affected hearing this.

We asked her: “Do you think a person could lose touch with things as a way of telling herself that she has used them wrongly?”

Jean Hartman. I’ve often wondered about that—its like I can’t get away with something. Then, I have a big desire to retreat and then I feel bad.

Consultants. Do you think you are trying to tell yourself, “Don’t retreat! Your deepest desire is to like the world and to use everything, including your husband for that purpose.”

As Mrs. Hartman continued her study of what this means, her life changed dramatically. Max Hartman himself said of Aesthetic Realism Consultations, this is “what men are looking for” and “what the family needs most to study.” Jean Hartman was so proud of her husband, she told us “I never felt so important. My marriage is really a success story!”

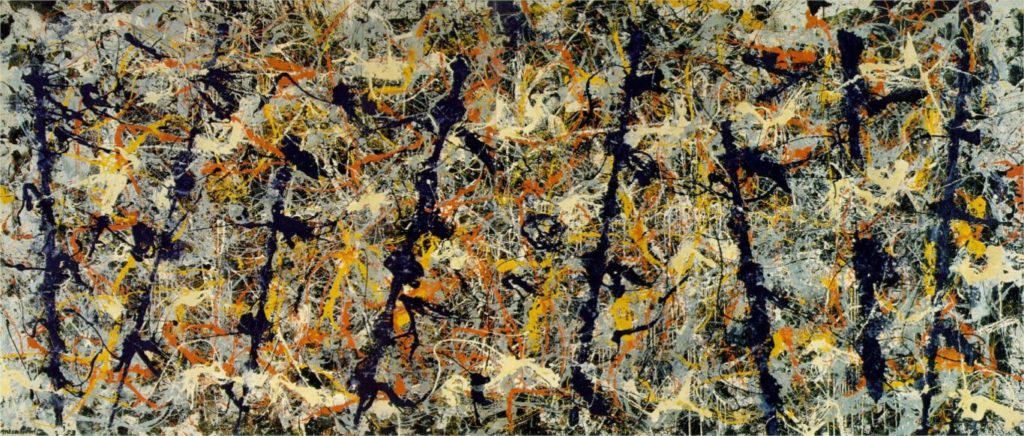

Aesthetic Realism shows that what Jean Hartman wanted, what Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock wanted, is like the technique of art itself. It is in Jackson Pollock’s beautiful painting Blue Poles.

Imagine it as almost as wide—as all his major works are—as this stage (15 feet 11 inches). This is a work of joyous criticism of false separation, because it includes, composes, enjoys so much! Those red loops and dancing swirls of paint, meeting, crossing over, bumping into the thicker white skeins are almost like two things—the motion of couples on a dance floor, and also far-off galaxies. Pollock used glass shards and aluminum paint—and there is a sharpness and luminosity at once. The Blue Poles, spaced rhythmically apart—are both firm and affected by the whirling in the spaces around them. We can see that in the ribbon-like extensions, like pennants in a windy space, a space that has depths beyond what we see.

We told Jean Hartman, “to respect the world from which all things come, which includes the things and people close to you, your husband, is to feel a thrill at existence itself.” The complexity of weaving here is a salute to reason and ecstasy as one thing. Aesthetic Realism explains what makes Jackson Pollock so popular: it is the dance of relation which is here, and which shows us our greatest ambition—to see the world as it truly is—a dynamic presence and oneness of opposites.

Aesthetic Realism is the means for satisfying that ambition all the time, sitting here, walking down the street, talking to another person, in whatever one meets—and I am very happy to be able to say this.