Aesthetic Realism Shows How

Art Answers the Questions of Your Life

By Dorothy Koppelman and Carrie Wilson, USA

31st InSEA World Congress, 2002, Teachers College, Columbia University, NYC

We are honored to present the new way of seeing art and its relation to life that we learned from the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel. We see it as the most valuable, exciting, needed approach to art and art education there is. We love it, and we are very glad to tell you about it today.

The philosophy Aesthetic Realism was founded in 1941 by the great American poet, critic, and educator Eli Siegel. A central principle which we will illustrate is his landmark statement: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Mr. Siegel has provided here the criterion for beauty, which we have seen is universally true. And he has answered, too, the question: What has this beautiful thing to do with our puzzling, imperfect lives?

Since 1984, the Terrain Gallery of the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation here in New York City, has presented, free to the public, a weekly series of ten-minute talks based on this principle titled: Aesthetic Realism Shows How Art Answers the Questions of Your Life. These are some that have been: “What Can Art Teach Us about the Family?: Monet’s ‘Terrace at Sainte-Adresse'”; “Black and White, Separate and Together in Robert Frank’s ‘Trolley—New Orleans'”; “Can We Show Outwardly What We Feel Inside?: Matisse’s ‘Blue Window'”; “What Should We Look Up To?: Louise Nevelson’s ‘Sky Cathedral. ‘”

As coordinators of the Terrain Gallery and of this series of over 175 talks, we have selected passages from eight of them, dealing with diverse works—from 16th century Persia to 19th century France, from medieval Russia to 20th century America. We will be quoting from talks of our own and those of our colleagues, Aesthetic Realism Consultants Nancy Huntting and Bennett Cooperman, and Aesthetic Realism Associates Barbara Buehler, Anthony Romeo and David Salmon.

In 1955, Eli Siegel’s 15 questions, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? were published by the Terrain Gallery, and the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Each of the excerpts you will hear deals centrally with one pair of opposites—such as Logic and Emotion, Freedom and Order, Grace and Seriousness, Continuity and Discontinuity—and shows that the technical questions of art, aesthetic questions, have in them the solutions to the conflicts in our lives.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that the deepest desire of every person is to like the world honestly, and that, we have learned, is the purpose of art, and all education. The impediment to liking the world, Mr. Siegel explained, and the pervasive interference to education, is the desire for contempt in a person—the feeling that if other things are ugly, stupid, boring, beneath us, we are more glorious. We have seen that contempt is the cause of all human cruelty. And the great opposition to contempt is the beauty in the structure of reality itself. Art is a necessity because it shows that beauty. This is the basis of the Aesthetic Realism education taught at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation by Ellen Reiss, Chairman of Education, and by the faculty.

There is a rich curriculum of courses—in the visual arts, poetry, music, anthropology, classes in education for teachers, classes for children, and more—which have been taught at the Foundation for the past thirty years, as well as art exhibitions, dramatic and musical events, and consultations for individuals in which the questions of a person’s life are looked at as aesthetic situations. Aesthetic Realism is being used with unprecedented success by educators in public schools. It is completely democratic; it counters snobbism and elitism of any kind because the opposites are present in every form of art, and in all people.

The first example today is by Nancy Huntting, who is an Aesthetic Realism consultant to women. Ms. Huntting is of the Terrain Gallery committee, and is coordinator of the international periodical The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known. She has written on the lives of the 16th century English writer Aphra Behn, the 20th century journalist Martha Gellhorn, and on Bruegel’s painting Hunters in the Snow and the subject “How We Can Be Truly Composed.” Here she writes on the difference between the way people customarily see, and the art way of seeing, studying Paul Cézanne’s great painting Still Life with Onions:

Familiarity & Wonder in Cézanne’s Still Life with Onions

by Nancy Huntting

Like many people, I felt familiar objects were mundane, not worth my notice, and as many people secretly do, that I was the most wonderful thing. This painting by Paul Cézanne, which I love, criticizes that contemptuous way of seeing. Here we see vegetables and domestic objects, like those I have used and put away without much thought. Cézanne found a meaning in them people all over the world have been stirred by. In ‘The Organization of Self,’ a chapter of Self and World, Eli Siegel explains that people separate the wonderful from the matter-of-fact, and he writes:

When Cézanne paints a common fruit he does not add to that fruit qualities which the fruit does not possess; he sees the fruit accurately—with unrelenting accuracy; nevertheless, through his accuracy a something beyond the fruit, a wonder beyond the vegetable is presented. Familiarity and wonder must be, and have been present in all true aesthetics. [pp. 136-137]

I learned that the wonder Cézanne found is the fact Mr. Siegel explained—that the structure of the whole world is in every object, the oneness of opposites, which is our structure, too.

Each object in this painting, each onion, has its own particular shape, definite and contained—yet every object meets and joins the others; the colors change and continue; energetic, disorderly green and brown shoots come forth form the onions almost as if they were feeling out their relation to each other and the tablecloth and space. This is a ‘still life,’ yet it is like a waterfall, a cataract of shapes and colors spilling across the table and over its edge. Cézanne shows in ordinary objects the drama of rest and motion, utter individuality and what Eli Siegel has described as “indissoluble…relation.”

The upright bottle is a staunch sentinel over this unruly bunch of vegetables—yet closely examined, its outline wavers, blurs with the air. The rim of the glass literally vanishes into air, mysteriously, as it reveals, blends with and changes the onion behind it. This is so different from the contemptuous desire a person can have to manage and dismiss people and objects, and have them vanish. The glory of Cézanne is in his humble and persistent respect for things. He shows the wonder in these domestic objects; in them, matter and space become each other.

I never saw an onion the same way after studying how Cézanne saw them. Look at the foremost onion on the dish. He wants to give it its full existence, its full depth and weight. Through brushstrokes that look so spontaneous and rough, yet are so careful and delicate, Cézanne builds subtle layers from vivid red-orange, to gold and white. Its outline is indicated on the right, yet through the colors within we feel a continuation of that roundness of shape in every bit of surface, until on the left it seems there is no outline at all, just color as form. It is breathtaking. Meanwhile, it is more beautiful through its relation to all the other onions, the white dish and tablecloth, the dark knife, glass and bottle—and it brings out their beauty in return.

Logic and Emotion

We continue now with two talks on Logic and Emotion—opposites which fight in the lives of most people. We feel and we reason—how can these two go together? In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Eli Siegel asks:

Is there a logic to be found in every painting and in every work of art, a design pleasurably acceptable to the intelligence, details gathered unerringly, in a coherent, rounded arrangement? —and is there that which moves a person, stirs him in no confined way, pervades him with the serenity and discontent of reality, brings emotion to him and causes it to be in him?

These two papers show what we can learn from art about these opposites in relation to that ever-so-popular, and ever-so-confusing subject, Love. The first is by Aesthetic Realism associate Barbara Buehler, who is an Associate City Planner with the NYC Dept. of City Planning. Ms. Buehler received her BA in International Affairs from George Washington University, and has written and spoken importantly on the cause and the solution to the housing crisis in New York City, most recently at the Campus Outreach Opportunity League hosted by Harvard University. This is her discussion now of a page from The Shah-nameh—The Book of Kings, a Persian Manuscript of 1527:

Logic and Emotion in The Book of Kings, a Persian Manuscript

By Barbara Buehler

People have felt tormented by the feeling that in love, mind goes out the window. I did. I felt I was one person at my job, using my mind on statistics and development plans, and another person in the evenings when I went out with a man. Through my study of Aesthetic Realism I am learning that true love, like art, is a oneness of opposites—mind and body, thought and feeling, logic and emotion. As I studied this detail from a page of a Persian manuscript, I was very moved to see how logic and emotion are one in this portrayal of two lovers.

This painting shows that as we are affected by the body of another and there is passion, the order of the world persists. There is luxuriousness, even abandon in the dazzling colors and shapes of tapestries, rugs, mosaics, urns, bed, pillow, cover. Yet each object has its own distinct order and is part of what Mr. Siegel describes as ‘a design pleasurably acceptable to the intelligence.’ We feel the presence of mind in every detail of every design. With all the opulence, nothing is gushy or out of control.

A woman wants to feel, as she is close to a man and is swept by him, that she is more intelligent, and through him, her life is more coherent. Aesthetic Realism teaches that the purpose of love is to use another person to have more feeling about the world through knowing it, being more exact about it. How much this is like the purpose of this manuscript, as described by Stuart Cary Welch in A King’s Book of Kings, The Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp:

…to delight and…simultaneously to instruct….At once a history, political text, and religious treatise, it is a compendium of the body and mind, the intuition and intellect, of an entire culture.

A woman, and a man too, can leave out and flatten the richness of the world—everything but the person he or she is with—thinking this is love. But we deceive ourselves. I did. The using of a person to lessen reality is really contempt for that person and for the world. In this Persian manuscript, there is flatness, but for the purpose of richness—all things are part of a scintillating design, and the lovers are a part of this design. In the lower center, the two lovers lie thoughtfully and quietly on a brilliantly ornamented red and gold bed under a deep blue cover, decorated with golden swans and a border that rises and falls as bodies together can. We are very aware of the two bodies beneath the cover through the beautiful curve made by the body of the man. Yet all we see are their heads, a little of his pink-clad arm as it lies over her shoulder, and his hand caressing her chin. Their eyes are open, and thought is accented, as their white headdresses silhouette their heads against the black and gold pillow. Their heads are placed carefully together, softly touching and in the carefulness we sense great respectful feeling.

A tall green candle burning before a red rectangle seems to complete the curving blue horizontal form of the lovers. This burning candle and red panel certainly represent passion. Yet placed as they are in the center of the design, they make for the intense feeling of symmetry it has. And look at the two pairs of slippers so carefully placed at the lower right and left of the picture on either side of a bowl of glowing red pomegranates. Welch writes, ‘The lovers’ slippers are as neatly tucked into the arabesque as they themselves are in the bed in this exquisitely chaste representation of passion.’

Love, like art, I learned, can be opulent, dazzling, ever so sensual and have precision too. ‘One of the purposes of art,’ writes Eli Siegel in Self and World: ‘is to have the intellectual felt concretely, even sensually; and to see the sensual as having possible form.’

Today, as my husband, architect and Aesthetic Realism consultant Dale Laurin, and I talk to one another, hold each other, we are more deeply, keenly aware of the meaning and richness of the whole world. We know this feeling will grow for the rest of our lives.

We go now to a very different work of 19th century France, and look at how Pierre August Renoir put together the same opposites, Logic and Emotion, as Carrie Wilson speaks on “What Can Art Teach Us about Love?: Renoir’s ‘Luncheon of the Boating Party.'” Ms. Wilson began her study of Aesthetic Realism with Eli Siegel after graduating from Barnard, having studied both art history and singing. In addition to her activities as part of the Terrain Gallery Committee, Ms. Wilson is a professional actress and singer, and teaches the course “The Art of Singing: Technique and Feeling” at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation. In April she took part in a presentation of “The Poetry of Eli Siegel” at Baltimore’s esteemed Enoch Pratt Free Library. She has seen that the oneness of opposites is the cause of beauty in all the arts.

Ms. Wilson brings to her understanding of the subject of love a twenty-five year career as a consultant to women. Her articles and papers on the lives of Maria Callas, Mary Garden, Maria Malibran and others have shown dramatically the necessity of putting together opposites in every aspect of our lives. Ms. Wilson’s paper begins:

What Can Art Teach Us about Love?: Renoir’s

Luncheon of the Boating Party, by Carrie Wilson

Eli Siegel asked me in a class: ‘Do you believe the dazzling time that will dissolve your questions is what you’re looking for? A period of intensity will drown all the questions you have, isn’t that right?’ He was describing accurately how I, like many women, saw love. That is what I had gone by, as people often do. But it makes us unable to respect ourselves, and unfair to the other person, whom we are using to get away from the world and triumph over it.

Mr. Siegel explained what I was really hoping for when he asked, ‘Can intellect ratify ecstasy? Do you know how much it is possible?’ I didn’t, and I love Aesthetic Realism for teaching that when we really care for someone, that care has knowledge and sound reason as its basis.

That intellect can ratify ecstasy is one of the large things Aesthetic Realism shows art can teach us about love. Renoir’s The Luncheon of the Boating Party, of 1881, over four feet high and nearly seven feet wide, is dazzling, even ecstatic—with its warmth, its manyness, its shimmering light and dark, and fresh, glowing color. Yet, as we look we find there is a wonderful structure there, a structure both symmetrical and unsymmetrical, which, as Eli Siegel writes in his question about Logic and Emotion: ‘pervades’ us ‘with the serenity and discontent of reality.’ For example, the painting is divided vertically into four equal sections—that is symmetry. Included in the two left sections are only three people and one dog. And on the right are all the rest. That is asymmetry. However, there is interweaving—light is in the heavy sections on the right: in the table cloth, a white shirt, that lovely creamy white jacket, glimpses of collars and cuffs, a bit of sky. And dark color gives weight to the light sections, as does the downward slope of the railing and the waving and geometric canopy. There are dazzle and logic both, and their oneness is what makes this painting great.

It is notable that in this whole painting of men and women there are no twosomes. In ‘Love and Reality,’ a chapter of Eli Siegel’s Self and World, he writes: ‘There is…a third partner to the relation of Edith and Jim. That partner is the world as a whole.’ One way or another we find Renoir paints a third partner. On the left a woman sits, affectionately holding a little dog, and behind them stands a man in a white shirt, looking into the distance. On the right, another man, also in a white shirt and wearing a yellow straw hat, completes a triangle with the first man and woman. Meanwhile, he is part of another group of three. He and the woman seated next to him, whose gaze is a lovely mingling of meltingness and inquiry, are encircled by the outstretched arms of the man standing behind them, leaning on two chairs. At the upper right of the canvas a man stands with his hand at the waist of a woman, who shows her uncertainty by holding onto her hat, while another man rests his hand on the first man’s shoulder. The whole painting has this motif of threes. This is part of what Mr. Siegel describes as ‘a design pleasurably acceptable to the intelligence; seeing this design, doesn’t the painting stir us more?

It moved me to see that the axis securing the whole composition is the man in brown. Unlike myself, who wanted to use a dazzling time to dissolve my questions, Renoir has placed, right in the center of this dazzling painting, a man with his back to us representing the world as unknown—and what’s more he paints him a sober, earthy brown. And see how the two diagonals which cross at his back hold all these figures together. I think Renoir was showing something here about the central importance of the world as mysterious, yet friendly.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that the purpose of love is to use a person to like the world. One of the great mistakes people make—I did—is to separate feeling about one person from feeling for all people, and for the world as a whole. To make a composition of many people you know, and to see a relation among them that brings out the meaning of each, is what is necessary in love. Renoir does just that here. The girl he loved and was to marry, Aline Charigot, takes her place with all the others. She is part of ‘a design pleasurably acceptable to the intelligence.’ She is the young women seated at the left, holding the dog.

To see a person truly, I have learned, we have to see how the opposites of the world are in that person. Renoir shows Aline Charigot as a relation of affection and profile, ruffle and elbow, dark and bright, intensity and gentleness. The red on the bodice of her dress stirs and satisfies, but in the way it is blended with the darker tones there is something uncertain. As she sits there quietly, it runs like a current, defining her form. Through color, qualities, and composition, she is related to everything else in the painting; as we see this our feeling for her is greater. Is she less for being dressed in dark purplish blue and capped in red like the wine bottles? No, she is more through relation, and she makes everything else more too. In Self and World, Eli Siegel writes:

A self can say to another being, “Through what you do and what you are and what you can do, I can come to be more I, more me, more myself; and I can see the immeasurable being of things more wonderfully of me, for me, and therefore sharply and magnificently kind and akin.” [pp.190-191]

This is a very passionate statement. It’s what goes on when education is at its most successful, and it is the essence of art. Renoir, I think, says that here. And he says it of every object in the painting. This is the logic of the emotion every person wants to have.

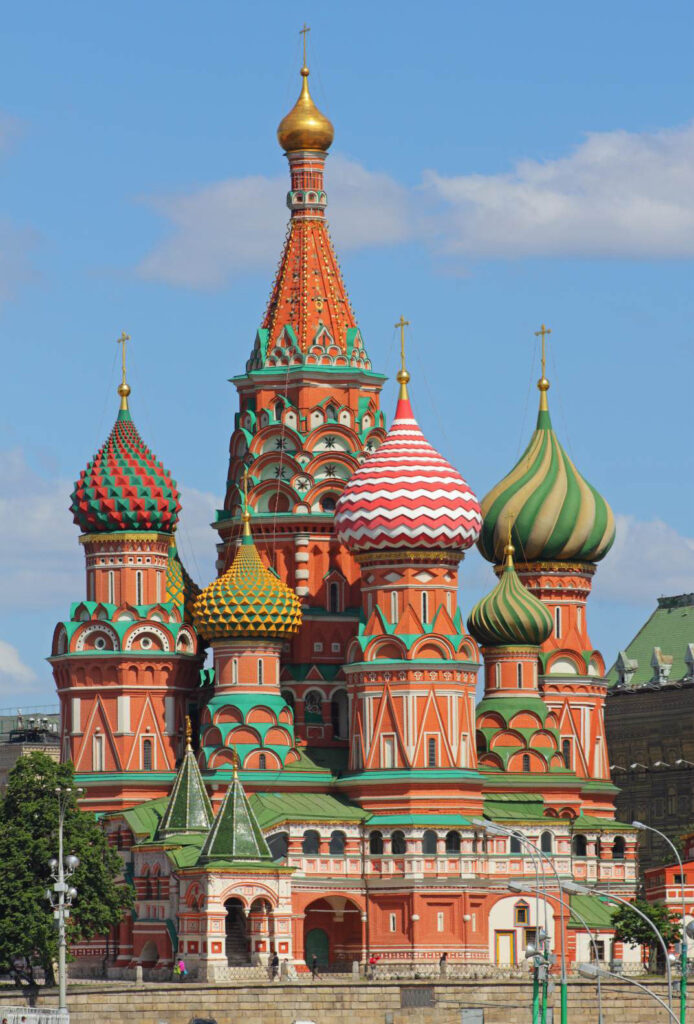

Freedom and Order

Aesthetic Realism shows that opposites are the means of integration of all the arts, and we go now to the art of architecture. We have chosen a talk on a building beloved by the Russian people for centuries, St. Basil’s Cathedral of Moscow, and another building which graces the New York skyline and is loved by people here—the Chrysler Building. All during what is called “the cold war” while our government saw our two countries as enemies, the deepest desire of every citizen was the same: to put together opposites in their lives. Every government on earth, to meet the hopes of its citizens, has to make a one of freedom and order, and has to learn from art. Order without freedom makes for restriction, conformity; and freedom without order makes for abuses equally cruel. Ethics and aesthetics, we have learned, are the same thing.

This is the question Eli Siegel asked about Freedom and Order:

Does every instance of beauty in nature and beauty as the artist presents it have something unrestricted, unexpected, uncontrolled?—and does this beautiful thing in nature or beautiful thing coming from the artist’s mind have, too, something accurate, sensible, logically justifiable, which can be called order?

The first talk is by architect David Salmon, who, graduating from Bowdoin, and with a BA in Architecture from the University of Tennessee, began studying Aesthetic Realism in consultations. A member of the American Institute of Architects, Mr. Salmon has spoken on Japanese screen painting as well as on works of architecture, and in his practice in Rye, New York, specializes in school design. This is a section of David Salmon’s talk; he has called it “What I Learned about Freedom and Order from St. Basil’s Cathedral.” (And we note that the humble onion became the crowning glory of this beautiful building.)

What I Learned about Freedom & Order from St. Basil’s Cathedral, by David Salmon

Some years ago, I was swept as I looked at this famous 16th century cathedral, so different from the more severe and controlled classically modern design which as an architect I had preferred. Its many turrets with their bold geometry of layered round arches and sharp triangular forms astonished me. And those onion shaped domes with their swirling patterns and bold colors seemed to dance atop these towers. I thought it was the most exuberant and energetic building I had ever seen. And looking from dome to dome, tower to tower, we find relation and difference at once and surprises at every turn.

At the time I began to study Aesthetic Realism in 1984, I saw the world as confusing, without reason or logical structure, and had contempt for it. Most things were neither interesting nor good enough for my enthusiastic response. I would stop myself as I began to have large feelings for fear of losing control, and thought people who did show their feelings were beneath me. Meanwhile I didn’t like myself, and yearned for honest expression. In my first Aesthetic Realism consultation, as I sat rigidly, expressionless, speaking in a monotone, my consultants asked me: ‘What do you think about honest enthusiasm? Do you think there is such a thing?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. My consultants asked: ‘Is the lack of it something you have against yourself? Is that something you’d like to change?’ It was, and it has!

I learned I was hoping to make a one in my life of freedom and order as they are made one in art. Studying St. Basil’s Cathedral, I saw that with its great sense of freedom—in form, pattern, and color—there was also great order. D.R. Buxton, in Russian Mediaeval Architecture, writes: ‘a rare beauty of proportion emerges from apparent confusion—an impression of tranquility, not chaos….’ [p. 44]

Each of the four chapels is crowned with its own lively turret and dome. The corner towers rise the highest, are octagonal, and have a similar pattern of decoration.

The towers between are shorter, round, and have three rows of round arched ‘kokoshniki’ at their base. These neat rows of semicircles make the towers seem to float freely in motion. I love the joyful, jaunty up and down rhythm of these towers. The domes, so alike in their onion shape, are surprising in the variety of their decoration. Their swelling form is both exuberant and tight at once; their line and pattern gracefully flowing and exactingly geometric. It is this oneness of freedom and order, the unexpected and the logically exact, that makes this cathedral so beautiful. It is why I care for it so much—and it shows these opposites can be one in our lives.

My study of Aesthetic Realism met my deepest hopes. I began having the emotions I yearned for all my life. Increasingly I have the enthusiasm I was looking for. It is a oneness of freedom and order—both unrestricted and accurate—and it is the same as what makes this magnificent cathedral of 16th century Russia so beautiful.

Talks in the series, Art Answers the Questions of Your Life have been given for 17 years and during this time one of the remarkable things the audiences coming from all over the United States and abroad have seen is that the same opposites make for beauty in painting, architecture, sculpture, photography, printmaking. And the oneness of opposites is the crucial thing whether the work is representational or abstract. For instance, actor and Aesthetic Realism consultant Bennett Cooperman shows how Freedom and Order are dramatically present in the contemporary painter Hans Hofmann’s famous abstract painting “Rhapsody.”

Bennett Cooperman graduated from Syracuse University’s School of Visual and Performing Arts in 1976. He has been seen in dramatic presentations of Eli Siegel’s lectures on the works of Shakespeare, Moliere, Sheridan and Eugene O’Neill. He has given seminars on issues that concern men today, such as “Does Our Anger Make Us Stronger or Weaker?”; “What Is a Husband’s Biggest Mistake?;” and “Flattery or Criticism: Which Do Men Truly Want?” This is from his talk on Hans Hofmann and the question “Can Exuberance Be Sensible?”:

Can Exuberance Be Sensible?: Hans Hofmann’s Rhapsody

by Bennett CoopermanTwo opposites that fought in me all my life and trouble many people are brought together in this painting: freedom and order. One form these opposites take is the exuberant and the sensible. Webster’s Dictionary defines exuberant as ‘joyously unrestrained and enthusiastic … overflowing…lavish,’ and sensible as ‘containing sense, judgment, reason.’ Can we be all these things at once?—reasonable and excited? Yes. In his book Self and World, Mr. Siegel asks this kind question: ‘What is it that painting—coming from the human mind—can do which the human mind itself can’t do? A person can ask about a picture, What has it got I can’t have?’

The actual size of ‘Rhapsody’ is over 7 feet high by 5 feet wide. The first thing I noticed were those three big orderly rectangles: red-orange, blue and purple. One is horizontal, two are vertical. Then, all around them is something looser, ‘unrestricted, uncontrolled,’—patches, strokes, and areas of orange, green, yellow, black, red and blue. And these two things don’t fight, they complete each other.

The title of the painting is ‘Rhapsody’ and I was taken by the work because I had been afraid to have feelings like that, emotions that were out of my control. As an actor this held me back, too. In a class for Aesthetic Realism consultants and associates, Chairman of Education Ellen Reiss asked me. ‘Do you think in some way you could let go more?’ That question had my whole life in it. And I am so grateful for what I’m learning, making it possible for me to have feelings about art, about people, that I never had before. I’ve been learning about what Eli Siegel write about in Self and World: ‘Beauty is good sense. It is hard good sense.’

Hans Hofmann is proud to show he is excited. And as he is, he is both accurate and free. The way these two things are in this painting is more subtle than it might seem at first glance—you could think the rectangles are the accurate part, and the strokes and patches are the free part. But on closer looking, you can see that the three orderly rectangles have vaguenesses, irregularities, and freedom too. The red-orange one spills out of its edge at the bottom, near the middle, and blends into the roughly painted blue area below. To the right, a blue rectangle exactly the same height as the red one is dropped and suspended in a light space. There is a sensation of something like gravity and floating simultaneously.

To me, the purple rectangle above is the most beautiful of all. It seems fixed and floating at once. Its edge is precisely defined and exact, but on the right and left sides, where purple meets green, the color shimmers a bit, there is something subtly ‘unrestricted, uncontrolled.’ Its singularity and its purple color give it a regal quality, but inside cool violet plays against warm violet.

Critic Erle Loran describes Hofmann’s exuberance and good sense. He writes of the ‘boldness of his color,…the ferocious energy’ and ‘daring to let go,’ and yet ‘there is always and inevitably a sound idea in everything he paints.’ This is not gushy emotion that is on top, exuberance that is devoid of logic and reason. That is what I was afraid of as a person—if I was really exuberant, I thought I would be insincere and mindless. Hofmann says no—what is bright, exuberant, and on the surface arises from weight, depth, logic. Seeing this, learning from it through my study of Aesthetic Realism, I am myself a more truly exuberant and sensible man, and I am more expressed as an actor, more variously than I ever hoped.

And now, we look at the New York landmark, the Chrysler Building, and what architect Anthony Romeo saw about himself through seeing how that beautiful building puts together opposites in its very structure. Anthony Romeo began his study of Aesthetic Realism, like Mr. Salmon, first in consultations, then in l978 he began studying with Mr. Siegel, and now attends the classes taught by Chairman of Education Ellen Reiss.

He has given talks on Palladio, Frank Gehry, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Frank Lloyd Wright and others, and in the Terrain Gallery series has spoken on what he learned from the Greek Classical Orders about Humility and Pride, and on how the opposites of Rest and Motion were more composed in him after studying the chairs of Gerrit Rietveld.

Mr. Romeo, a co-founder of Urbane Architects in New York City was one of the persons on the Aesthetic Realism panel speaking on the crisis in public housing at Harvard in 2001. He teaches a class for children “Architecture and You” at the Children’s Aid Society in New York City, and as a member of the American Institute of Architects has spoken on the subject of health care design in conferences throughout New England and the Eastern seaboard. Mr. Romeo begins:

Can We Be Both Lighthearted & Serious?:

The Chrysler Building Shows How!

by Anthony RomeoFew buildings have had the kind of impact on the hearts of New Yorkers that the Chrysler Building has had. I remember seeing it from the back seat of our car as my family drove to Yonkers, when I was about 5 or 6, and having a sense of awe. I believe the reason it has moved and inspired people for more than seventy years is in this question about Grace and Seriousness from Eli Siegel’s ‘Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?’

Is there what is playful, valuably mischievous, unreined and sportive in a work of art?—and is there also what is serious, sincere, thoroughly meaningful, solidly valuable?—and do grace and sportiveness, seriousness and meaningfulness, interplay and meet everywhere in the lines, shapes, figures, relations, and final import of a painting?

People don’t know how to be serious and lively at the same time. I didn’t. Even as a child I could be very glum and humorless about myself. My mother would say, ‘Here comes Mr. Misery, with the weight of the world on his shoulders.’ I didn’t know the reason I felt so good when I looked at the Chrysler Building, is—as I was to learn from Aesthetic Realism years later—because this towering structure was doing what I wanted to do: it showed me that seriousness, meaning, solidity could be the same as lively, sportive, graceful fun. In fact, when you’re truly serious, that’s when you’ll be most graceful.

The Chrysler Building was conceived in the early 1920s, and completed in 1930. Many architects disliked it when it was new, and the building’s designer, William Van Alen was called ‘the Ziegfeld of his profession.’ Most often we don’t think of a skyscraper as having humor, but the Chrysler Building brought something new to architecture, and it has big meaning.

Where else could you find brickwork designed to look like automobiles, and the employment of actual hubcaps from 1929 Chrysler cars bolted into the brickwork, right in the center of the tire, where it belongs?

And here at mid-height, where the base of the building becomes the tower, giant winged radiator caps, modelled after those used in the same 1929 Chryslers, accentuate the graceful, outward curve of the building. This brings exuberance to what might otherwise have been a heavy base, and from this level the graceful tower rises. It is crucial that none of these elements seem ‘stuck on.’ William Van Alen saw an authentic, integral relation between the fixed, structural solidity of a building, and the dynamic, gleaming attributes of a motor car.

At the base of the tower, eagles, fashioned after Chrysler hood ornaments, thrust outward—like the gargoyles of Notre Dame cathedral. Then there is that majestic spire constructed in gleaming stainless steel, which crowns the New York skyline with exuberant, noble grace. And so what is serious and ‘solidly valuable’ is made one with what is playful and mischievous. Isn’t this is what we want to do?

In an Aesthetic Realism lesson I was privileged to have with him, Eli Siegel asked me, ‘Do you like humor?’ I answered, ‘Yes, but it’s interesting that I don’t have much. When it comes to telling a joke or having a sense of humor I can be very heavy.’ Mr. Siegel saw humor as one of the deepest subjects there is, and I am so grateful he encouraged me to have a better sense of humor about myself. For example, he said: ‘Space and Romeo have this in common: they both have room for improvement.’ And he asked: ‘Do you believe your questions are distinguished and pretty much alone?’ I did, and throughout this lesson he showed, with deep, critical kindness and humor, that what I saw as my distinction; being so different from other people—at times, as I thought, so much better, higher, more noble, and at other times lower than a hubcap—was really a fake, inaccurate way of being distinguished: puffing myself up through having contempt. He showed me that I was related to every object and every person through the opposites—and enabled me to feel my life had more meaning than I ever imagined, and that I could be graceful about what troubled me, not a grim, towering mope.

Can a person learn from this building how to have tremendous stature and also friskiness and grace? Did the architect who designed this have respect for both aspects of reality? To take a hubcap and place it on top of a skyscraper, is saying: ‘I’m bringing this seemingly lowly object high so you see its meaning and respect it’—that is both beautiful and ethical! And just as this is the same building from top to bottom, so a person hopes to feel we are the same person when we are lightsome as when we are deeply thoughtful.

The most outstanding aspect of the building is its spire. The gentle curves are graceful and reposeful. The triangular windows follow the curves, but accent playfulness and surprising, critical energy. When the original plan to light these windows at night was found some years ago, they were lit up. In their energy these triangular windows seem to mischievously contradict the quiet repose of those curves—but really they work together beautifully. One reason I care for my wife, Karen Van Outryve, is that while she can be very thoughtful, she can also be funny at just the right time, in a way that criticizes my tendency to ponderous sobriety.

Looking at the Chrysler Building, one has an emotion about the whole world. Eli Siegel said that humor is close to religion, and I, like many other people, have felt there is something about the Chrysler Building that is religious. I am so grateful to Mr. Siegel for describing what beauty is, and for giving me a chance to have these opposites—grace and seriousness—closer in myself through seeing how they are one in a building I have loved all my life.

We conclude with Dorothy Koppelman, founding director of the Terrain Gallery, on the opposites of Continuity and Discontinuity in two very different paintings—one which is seen as a courageous depiction of the horrors of war—Picasso’s Guernica, and the other, a pastoral celebration of life—Seurat’s Bathers, Asnieres.

As a consultant with the teaching trio The Kindest Art, painter Dorothy Koppelman speaks to artists about how they can have the same purpose in their lives they have in their work. She is co-author of the book Aesthetic Realism: We Have Been There, and teaches the course “The Critical Inquiry” at the Foundation. She has taught printmaking and drawing at the National Academy of Design. Her studies of artists—Mondrian, van Gogh, Velasquez, Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, Degas and Mary Cassatt—to name some, have shown her that in the 20th century, and now in this century, a universal criterion for what makes a work of art either good or bad has been come to, and that Aesthetic Realism is the means of closing the gap between art and life.

She and her husband, printmaker Chaim Koppelman, began their study with Mr. Siegel in the early l940’s. Mrs. Koppelman’s paintings have been exhibited in major museums, and a book of Poems and Prints is in the collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Her work can currently be seen in New York at the Terrain Gallery and elsewhere.

Continuity and Discontinuity in Picasso’s Guernica,

and Seurat’s Bathers, Asnieres

by Dorothy Koppelman

Picasso’s mural, seen as the symbolic painting of the horrors of war, is great because it shows, even as it takes on the cruelty and seeming non-sense in the world, that there is form, there is organization, there is something larger than man’s “inhumanity to man.” In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, The Fifteen Questions which are the most beautiful ever asked about the art of the world, Eli Siegel asks about Continuity and Discontinuity:

Is there to be found in every work of art a certain progression, a certain indissoluble presence of relation, a design which makes for continuity?—and is there to be found, also, the discreteness, the individuality, the brokenness of things: the principle of discontinuity?

Continuity and discontinuity are at the beginning of the passionate idea for this great mural, and they are in every detail of its technique. When the fascist bombs struck the Spanish town of Guernica in the middle of the night of April 26, 1937, the horror Picasso felt was like lightning striking him; and that light is in this painting.

It is one of the great purposes of art to make the ugliness of things bearable, and to show those things as continuous with what we see as beautiful. Picasso’s Guernica has done that with an impact that has affected the world.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that injustice and the cruelty of war should be energetically opposed; not used wrongly as a sign that reality is senseless, to say beauty is not real, and then give ourselves the right to flatten the world, elevate ourselves, and have contempt for everything. Picasso used art to oppose injustice; he used flatness to show the meaning, the ‘indissoluble presence of relation,’ the sensible structure of things which has us like the world on an honest basis.

‘The brokenness of things’ Eli Siegel describes is here in the fallen, heavy bodies on the bottom edge, the broken sword, the open mouths with teeth showing. All this is in a classic, eternal triangle, at the apex of which there is a light. To see death in the light is to give continuity to discontinuity—we see it with living eyes. And Picasso has put a bulb made by man into the eternal sun, right near the lamp over the stricken horse.

In particular detail and as a magnificent whole, the Guernica mural has what Eli Siegel has said all art must, ‘a design which makes for continuity,’ of life, of death, and of reality.

George Seurat’s Bathers, Asnieres, painted in the last decade of the l9th century, is a moving and deeply pleasing presentation of these same great opposites, Continuity and Discontinuity: it has that ‘indissoluble presence of relation’ in such a quiet, assured way, that all the motion in, the ‘brokenness of things’ is felt at once and you feel satisfied. The symbol of the ongoingness of life is here; the flowing river. And the light which permeates this landscape of grass, water, people—placed in what seems an eternal rightness—is achieved by blending and contrast, a technical form of continuity and discontinuity essential in painting.

Seurat’s pulsating dots of contrasting colors—oranges and greens, blues and yellows—are so close they blend to make a luminous, or contrastingly, a shadowy haze. Seurat described his scientific oneness of technique and emotion: ‘Gaiety of tone is given by…light and warm colors; calm of tone by an equivalence of warm and cold; sadness of tone by the dominance of dark;’ [Artists on Art, p. 374] and all are linked with downward, horizontal, and upward linear directions.

Right in the center of the painting these directions are present in a life-like tumble. The downward slope of a man’s legs is countered with a little casual mound of up and down, dark and light cloths just tossed there on the grass, and a stabilizing circle of a light hat makes a one of ‘relation’ and ‘discreteness.’

Look at the different circular shapes of hats and heads going from the lower left—dog’s head, bowler hat, high straw hat, low straw boater hat, round brown cap of hair, and finally, red hat. And the upward direction of the grass joins the angles of knees in three boys—one sitting with his legs in the water, one with his knees drawn up and elbows resting on them, and three, in the white figure in the distance. These motions—up, down and across are related so gracefully.

One of the most important things I have learned from Aesthetic Realism, that has made me happy—and Seurat represents it visually—is to see how wrong I was in thinking I was mainly separate from, discontinuous with other people and things. Most people in the park gazing at the water, on a subway train, or in a living room—do not see other people there as deeply continuous with what we are, from our atoms to our hopes.

Mr. Siegel asked me in an early Aesthetic Realism lesson ‘Do you think you are the only lonely person?’ As soon as I thought other people might be lonely, I felt less so. And as I learned that every person, every thing in reality is related to every other person and thing through their structure of opposites, I never felt lonely in the same way again.

Wrote critic Marc S. Gerstein: ‘The figures and setting are locked together in a sequence of intersections, echoes, and alignments.’ For example, the figure nearest to us is stretched out diagonally in one direction and looking out in another—like his dog. The angle formed by the dog is like the angle of the man’s shoulder, which leads up to—even fits within—the angle of the knees of the figure behind him. This boy’s arms and legs lead us down the grassy slope to the thoughtful boy seated on the river bank.

Mr. Siegel asked me once if I were the same person being active as I was resting—for instance, ‘Do you still answer to the same name?’ I was surprised because I had felt such a break between these two aspects of myself, something Seurat in his painting does not do.

Studying how Seurat puts opposites together is a beautiful criticism of the way a person can—and I have—asserted individuality through separation, and which is essentially the contempt that is against art, and life itself. Here, Seurat shows how wrong that idea is, how limiting. He has a red-hatted boy standing with his legs deep in the blue water, raising his arms in a call. I see this culminatingly as the call of life; it rises from the quiet motion, the depth, the thought and warmth of the whole painting, the scheme of things. These bodies, each one eternally under his own skin, in his own thoughts, have that ‘discreteness, the individuality…the principle of discontinuity,’ but there is ‘a certain progression, a certain indissoluble presence of relation’ which is true to reality itself at its atomic beginning.

We close this talk with sentences by Eli Siegel from Self and World which we love and which point the way to a magnificent future for art education around the world:

There is no limit to how art can be used to make life more sensible. To see art as making life more sensible it is first required of one that he respect art, know what it is, not make it less than it is.

Art, Aesthetic Realism believes, shows reality as it is, deeply: straight. All art does that. The possibilities of reality are reality. The more we see reality as having order and strangeness, form and wonder, the more reality we are seeing. Art is a way of seeing reality more by seeing it more as it is.

[Eli Siegel, Self and World, Definition Press, NY]

◊ ◊ ◊

Bibliography

Buxton, D.R. Russian Mediaeval Architecture. Macmillan, 1931

Goldwater, Robert, and Treves, Marco, eds. 1945, Artists on Art. New York: Pantheon Books.

Loran, Erle. Hans Hofmann. Los Angeles: University of California, undated.

Siegel, Eli. Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? New York: Terrain Gallery, 1955.

Siegel, Eli. Self and World. New York: Definition Press, 1981.

Welch, Stuart Cary. A King’s Book of Kings, The Shah-Nameh of Shah Tahmasp. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972, reprinted 1976.