By Marcia Rackow

The first time I saw Alexander Calder’s Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, I loved it! I was 7, and my parents had taken me to the Museum of Modern Art. The mobile hung from the ceiling above the stairwell, all the parts were turning ever so slowly in the air, and I thought it was wonderful!

Then, in the garden I saw his Whale. It was all black and sitting on the ground, but it seemed light and joyful.

Now, many years later, I admire Calder’s work even more, as I see the large meaning it has for people everywhere and how it answers a central question of my life.

One of the most popular artists of the 20th century, Alexander Calder revolutionized sculpture, added a new dimension to it—motion! He was, said Eli Siegel in his great lecture on sculpture, Weight As Lightness, “[one of] the people who just play topsy-turvy with the older notions of sculpture.” His mobiles were a new art form, and his monumental stabiles, which are stationary—

—have enlivened public spaces all over the world. Throughout his long career, Calder’s work extended into many fields: wood and wire sculpture, jewelry, household utensils, toys. He painted in gouache; designed book illustrations, tapestries, an acoustic ceiling, the sets and costumes for a ballet. He even painted a car and planes.

“Very few works of art,” wrote his friend, the critic Jean Lipman, “can make us feel light-hearted the way Sandy Calder’s do.” The reason is deep, and is explained by this landmark principle of Aesthetic Realism: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Calder’s work puts together joy and depth, lightness and heaviness in a way that makes for what people everywhere are yearning for. In one of his definitive essays on art, Mr. Siegel explained:

Art makes the world less heavy, and oneself less heavy. In art lightness is seriousness, also, because it is a lightness based on things truly seen, not on things evaded.

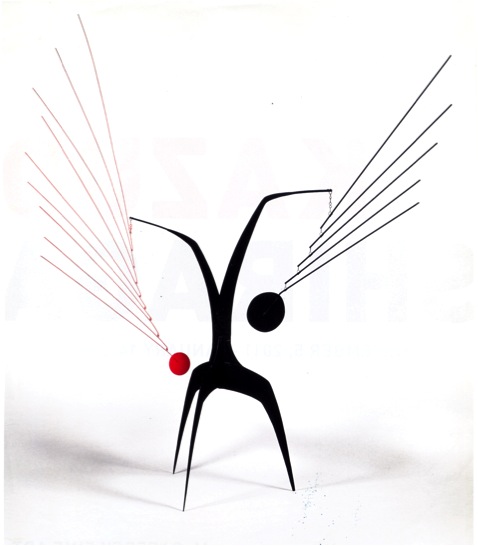

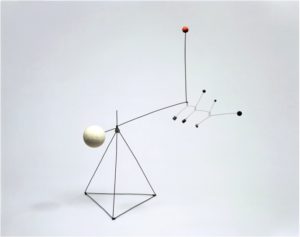

In this sculpture, nearly 5 feet high, Un Effet du Japonnais of 1941—

Calder combines the fixity and weight of a stabile and the motion and lightness of a mobile. He also combines his two favorite colors—red, which has brightness, and black, which has depth. But the way they are combined is what makes this sculpture beautiful. The base, a three-legged slender black shape with long legs coming to delicate points, and the two rising, narrow, curved vertical forms that bend out at an angle at the top, are an amazing relation of weight and lightness, severity and grace. Suspended from the upper arms, and fitting within the angular curved spaces, are a mobile in red and one in black, almost like delicate wings. The black one has more weight because the slightly irregular black disk is about twice as large as the red one, and the five long straight rods rising on jaunty diagonals above it are heavier than the delicate red ones. Yet this black shape is suspended much higher than the red one, giving it more lightness.

Lightness Despite Perception

In my life, these opposites—lightness and seriousness—were worlds apart and caused me pain. Growing up in Jamaica, Queens where I lived with my parents and relatives, I saw the quarrels and painful silences that went on and thought of myself as the peacemaker. I acted like Miss Sunshine—their salvation. I wasn’t interested in what they felt—I just wanted to have things pleasant, on the surface. I saw them as weak, needing my ministrations, and thought, in Shakespeare’s words: “What fools these mortals be.” Meanwhile I saw other people the way I saw my family, assuming I was smarter, superior to everyone. The way I made light of people, mocking them in my mind while putting on an affable show, made for an awful combination in me of heaviness and lightness; I felt both weighed-down and empty. Contempt—“the false importance or glory from the lessening of things not oneself”—I was later to learn, always makes opposites fight. And while I tried to charm men with my lightsome, girlish ways, my relationships always ended painfully.

Art, I felt, was my only refuge. I thought it was a purer, more beautiful world, not sullied by the confusions and messiness of people. Mr. Siegel once asked, “There are no torn papers in the Renaissance, are there, Ms. Rackow?”

In my late 20s I wrote in my diary:

Life does hurt. And we know it. And if our choice is to remain here—and not to give up and die as reason would tell us, then the only way to live is with joy. To create joy. To spread joy. Because in spreading thought and criticism, we only bring pain….So we must run the other way. Float—insulated. That is the only escape.

This cynical way of seeing had me almost give up painting, feeling my work too was meaningless, thin, insubstantial.

Then, I had the great good fortune to learn about and begin to study Aesthetic Realism. In a class, Mr. Siegel saw the pain I was in about seriousness and lightness, and he asked me: “Do you think that every time you work at something in art, your purpose is to make the world better?”

Marcia Rackow: Yes.

Eli Siegel: Still, do you think that you’ve suffered because you haven’t wanted to be serious?

MR: Yes, I think I’m beginning to see that.

He showed me that to be serious you have to be happily interested in people and things, to feel they matter, and to want to be accurate about them. He asked:

ES: Do you think you’d rather see something—even with your care for painting—as frivolous rather than mighty?

MR: I have preferred that, yes.

And then he asked: “Do you think seeing things more deeply and truly will make you more happy?”

MR: Yes. I think so.

ES: Do you think that’s what most people think? People think that they can select—that to see the surface of things, the agreeable surface, it’s enough.

MR: Yes, I’ve done that.

I thought about the conversations I’d had with my friends, flattering them and pointing out the flaws in other people who we felt were not intellectually or artistically up to our standards. I also thought about my feeling that it wasn’t polite to go too deeply into other people’s affairs. I realized, too, how terrified I was to get involved with any man.

Then Mr. Siegel explained:

There are many persons who are interested in art….However, they do not see that what they’re after in looking at a painting or listening to music is what should be sought for in a person.

I needed to see, for instance, how my parents, Sylvia and Leo Rackow, were trying to put together opposites that Calder puts together—and I’m glad to say they both liked his work. My mother loved to dance, especially the rhumba, but she also read Nietzsche. And in her work as a fashion designer, she created coats and suits with a serious, dignified line but also a flair. And my father, whose advertising designs at their best had weight and power, often could be lightsome and humorous. Unlike his best work, in his life, the way he could get into moods—go from lightness to heaviness—was not in the best relation.

After this lesson, which I told them about, my conversations with my parents became deeper, and I was more interested in their lives. It was also the beginning of a large change in how I saw all people, and it made real love possible for me. Now, in my marriage to filmmaker and consultant Ken Kimmelman, I benefit from his honest love for humor—sometimes used critically on my behalf—and his seriousness about art and ethics. He’s encouraged greater depth in me.

A Necessary Question for People

“How weight can be made non-oppressive is a necessary question” for people, wrote Mr. Siegel.

Whenever a weight is taken from us, we’re in the mood equivalent to our wanting to dance a jig—once we see the weight as lifted.

This was the question Calder was dealing with in all of his work. “He forsook the earthly SOLIDS, the laborious, heavy masses, and tackled space,” said his friend Robert Osborn, the political cartoonist. The important artist Fernand Léger wrote of Calder’s work: “It’s serious without appearing so.”

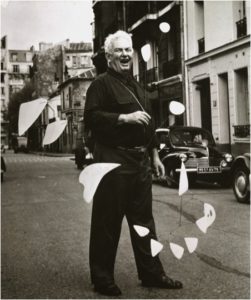

And those opposites, lightness and heaviness, were of the man himself. Alexander Calder was a big, robust man, yet he made some of the most delicate, airy sculptures ever created. Known for his good spirits and humor, he said he had “a big advantage,” as he was “inclined to be happy by nature.” He was, Osborn wrote, “a lover of fun, full of wit and play, but confronted by things evil he is as grim a battler as one could ask for.”

One of the works he was proud of is his Mercury Fountain for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.

It stood near Picasso’s Guernica and a mural by Miró, who was to become his life-long friend.

Meanwhile, there was something that troubled him which has also troubled other people, including me. I think Calder was in a deep fight between a true desire to respect the world and people, and the desire to be scornful. In the book The Three Alexander Calders his sister Peggy describes a letter he wrote to his parents in 1930 as having “an uncharacteristically misanthropic note.” He writes:

I seem to be bored by people in fairly short order—after having embraced them quite warmly to begin with. I suppose I see the pleasant side of them first, and really am in accord, but get annoyed with their little habits that keep repeatedly appearing.

He then goes on to enumerate his annoyances. Mr. Siegel once asked me if I saw people essentially as “boring and vexing.” I know this way of seeing people weighed me down and I believe that it was present in Calder’s conflict about how close to or distant from others he should be. It is these very opposites he was dealing with in his art. Explained Mr. Siegel:

The feeling that things oppose each other, get in each other’s way, are aloof from each other, is one of weariness and heaviness. But any time opposing things blend there is the relief which makes for true lightness.

Born in Philadelphia in 1898, Sandy Calder, as he was known, grew up in a family of artists. His mother was a painter, and his father and grandfather were both famous sculptors. As a boy he loved working with his hands. It can be seen in this early Self-Portrait he did at the age of 9.

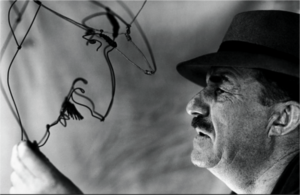

He later went on to study mechanical engineering. But after several jobs, including on a freighter and at a logging camp, he returned to New York to study at the Art Students League, and worked as an illustrator on the Police Gazette, covering the circus, where he drew the animals and had a great ability to capture their character, their weight, and motion in a single energetic line.

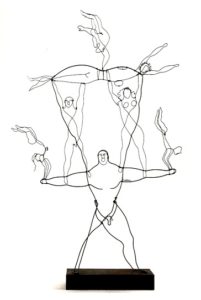

In 1926 he went to Paris, and while studying there, created his now famous Circus with figures and animals made of wire, bits of cork, fabric, string.

They moved and performed wonderful feats through the ingenious methods Calder devised. Soon his Circus captured the imagination of the Paris avant-garde. Mondrian, Léger, Duchamp, Miro, Arp, Cocteau and many others came to see his performances and were enthralled by them. He then began making his humorous wire sculptures—figures and portraits of his friends.

But it was a visit to Mondrian’s studio in1930 that, he said, “gave me a shock that started things.” Calder was enchanted by the studio, with red, blue, and yellow rectangles tacked to the white walls which he imagined in motion. “Now at 32,” he said, “I wanted to work in the abstract.” His wire sculpture took a new direction.

What a relation of space and matter! “A truly serious artist,” Calder said,

must follow the greater laws, and not only appearance. From the beginning of my abstract work…I felt there was no better model for me to choose than the Universe….Spheres of different sizes, densities, colors and volumes, floating in space…the greatest variety and disparity. I work from a large live model.

And Calder asked, “Why must art be static? The next step in sculpture is motion.”

In his new motorized sculptures, the first “mobiles,” there was a rhythmic motion of an object fixed to a base. But he soon felt that these were too regular and limited in motion, and started working with free floating forms.

“Just as one can compose colors, or forms,” he said, “so one can compose motions.”

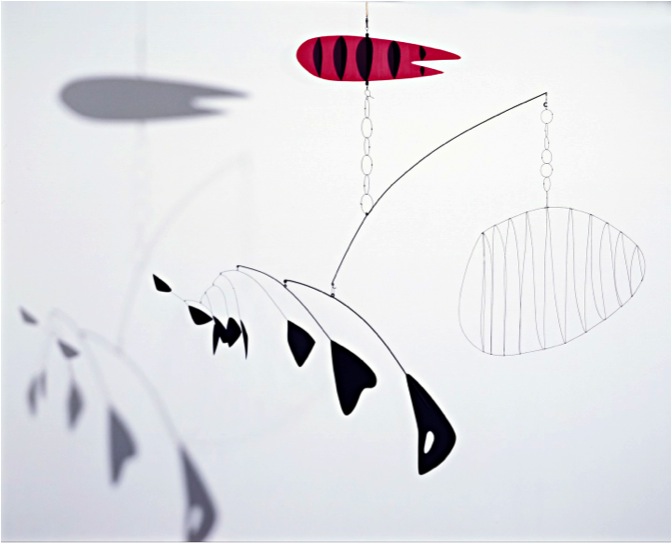

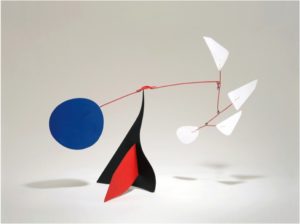

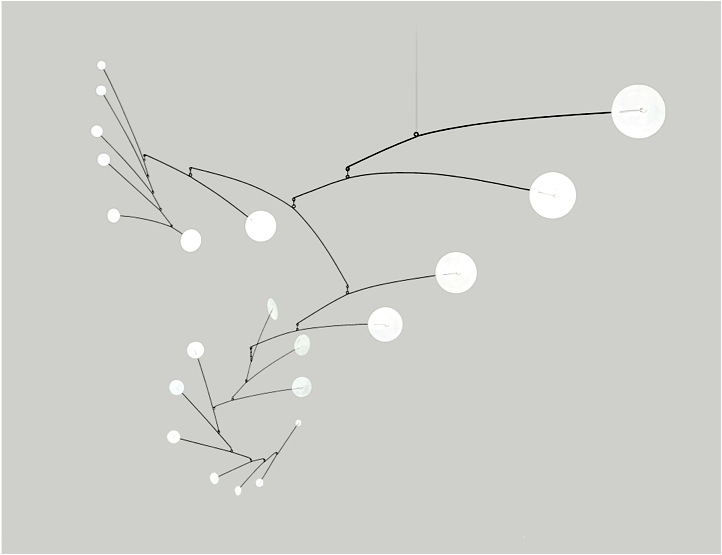

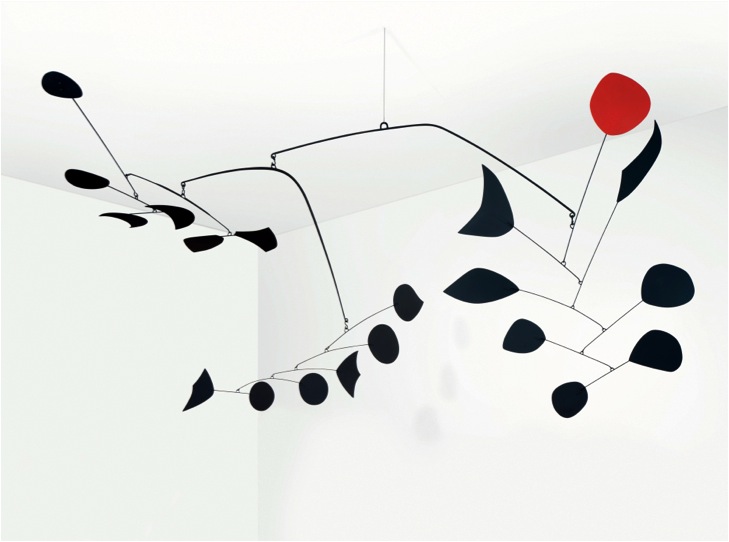

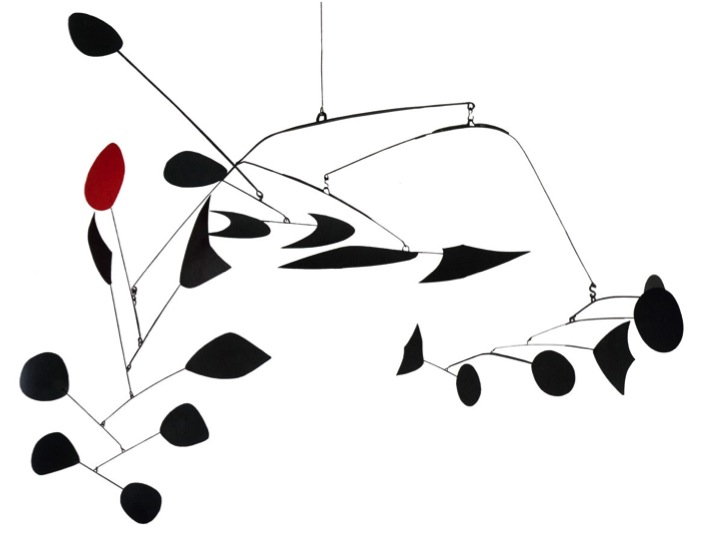

That’s what we see in this wonderful mobile Rouge Triomphante.

Calder’s composition is a beautiful relation of weight and lightness with that surprising singular red disk rising triumphantly among the many black curved, pointed, angular flat disks. In his work, no matter how delightful, Calder never leaves out the awry, the jutting, even the ominous. It includes the weight of the world as it gets to lightness.

The seven black forms on the right, rising irregularly, seem to have tossed that red disk in the air, as the slender curved form near it almost cradles it. We see Calder’s exquisite sense of matter and space as those forms are placed in an exact relation to one another so that they’re perfectly balanced on those slender wires. They seem to reach out organically from a living center. These forms oppose each other in shape, but they don’t get in each other’s way, nor are they aloof from each other. In their difference and relation in motion, they enhance each other, bring out each other’s individuality. I think this is what Calder wanted to feel in his life—that he could be close to people and feel that their differences did not lessen him, but added to him.

As the three sections of the mobile move in space, they are apart from each other and also move within each other’s paths, yet we don’t feel anything languid or weighty. Does seeing this counter the feeling we can have, that other people are obstructions, get in our path, and can weigh us down? In this mobile opposing things are composed in a way that makes for true release.

Consultations; or, Aesthetics in Process

The question Calder was dealing with in his work is what Jackie Ellwood was concerned about in her life. An attractive young woman interested in art, Ms. Ellwood works as a librarian in New Jersey, conducting after-school reading programs for young persons. She talked with brightness and energy about her work, but her view of things was often darksome and heavy, seeing people and things as interferences and burdens. In a consultation, she spoke about her recent engagement to Andrew Talbot and expressed her trepidations about this big new step in her life. We asked:

Consultants: Has Mr. Talbot been critical of your tragic bent? Does he have a more vibrant view of reality than your way of meeting things?

JE: Oh, yes. There’s a liveliness he does have. One day I started to go on about being overwhelmed with what I had to do and he nipped it in the bud.

Meanwhile, she could also be too light about things. She told us:

JE: But I still see where I can be terrified of going deeper….I want to be liked, and not rock the boat too much.

Consultants: Do you think that’s one of the big dangers between a man and a woman?—“Don’t bring up this and don’t say that”—and then you don’t respect him for liking you on that basis.

She later said self-critically,

JE: Yes. Somewhere I see myself as being useful to a man rather than being really deeply affected and changed by him.

Consultants: Could you say straight: “I see that I’m terrifically affected by Mr. Talbot and at the same time I feel I want to put a limit on it.”

To better understand the debate she was in about how close she wanted to be to her future husband, how deeply she wanted to be affected by him, and by other people, we suggested she write: “What is the fight I’m in? Which way will take care of me?”

Here is part of what Ms. Ellwood wrote:

The way I have cherished my privacy and erected a wall around myself has really weakened me: stifled my self-expression, has made me feel unnecessarily unsure of what is good in myself. I see how I am less Jackie Ellwood through insisting on this false separation.

As Ms. Ellwood saw that these choices had hurt her life and didn’t really represent her, she changed. Later, she did marry Andrew and her life is flourishing. She told us she feels more truly lighthearted and grounded, more truly alive, at ease and happier!

Can We Welcome “The Seeming Jars of Reality”?

Mr. Siegel wrote:

The seeming jars of reality are looking for tranquilization; the steep discrepancies for understanding; the weight of reality for true lightening.

Calder was not after an easy, smooth solution to the problem of weight and lightness, but felt that art had to include and give form to the disparities, the awrynesses of the world.

The mobiles—

—and stabiles—

— he built over the next decades are a testament to his desire to get to lightness by including the heavy, the discordant. In this majestic sculpture titled La Grande Vitesse—

—which Calder created for this plaza in Grand Rapids, Michigan, he gives “the weight of reality” “true lightening.” This sculpture, composed of tons of steel and painted that Calder red, soars upwards towards the sky. “I love red so much,” he said, “that I almost want to paint everything red.” “Red,” Mr. Siegel once said, “is the color of life,” and that is what we feel—this sculpture is alive! Composed of 27 flat plates of steel, these large, curved, arching forms join and intersect at angles creating a sense of volume, as they rise in the air and rest on graceful feet.

Then, surprisingly, as you walk around the sculpture, it looks so different—wider, more enclosed, heavier, resting on the ground, yet we feel all “the seeming jars of reality” go together, have found “tranquilization.” In Calder’s masterful hands, “the steep discrepancies” of curve and straight line, surface and depth, outline and color have found “understanding” and we are thrilled, because, “the weight of reality” has found “true lightening.”

What Calder achieved in his art is what all people are hoping for in their lives—and they can learn how to have it through the study of Aesthetic Realism!

1. Eli Siegel, Weight As Lightness, (unpublished MS, Eli Siegel-Martha Baird Foundation, 1951), 4.

2. Jean Lipman with Margaret Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), 18.

3. Eli Siegel, Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism (New York: Definition Press, 1981), viii.

4. Eli Siegel, Art As Gaiety (New York: The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, No. 851, 1989).

5. Eli Siegel, Aesthetic Realism class, 1974.

6. Marcia Rackow, unpublished journal, 1961.

7. Eli Siegel, Aesthetic Realism Lesson, October 13, 1978.

8. Ibid.

9. Eli Siegel, Art As Gaiety (New York: The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, No. 851, 1989).

10. Alexander Calder and Jean Davidson, An Autobiography with Pictures, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), 7.

11. Jean Lipman, Ruth Wolfe, Calder’s Universe (New York: The Viking Press, 1976), 47.

12. Jean Lipman with Margaret Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), 18.

13. Ibid., 88.

14. Margaret Calder Hayes, Three Alexander Calders: A Family Memoir (Middlebury, VT: Paul Eriksson, 1977), 236.

15. Eli Siegel, Aesthetic Realism class, 1972

16. Eli Siegel, Art As Gaiety (New York: The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, No. 851, 1989).

17. Jean Lipman, Ruth Wolfe, Calder’s Universe (New York: The Viking Press, 1976), 112.

18. Ibid., 112

19. Unpublished, MS, 8 March, Calder Foundation Archives, New York.

20. Jean Lipman, Ruth Wolfe, Calder’s Universe (New York: The Viking Press, 1976), 18.

21. Jean Lipman with Margaret Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), 46.z

22. Ibid., 52.

23. Aesthetic Realism consultation, 1995

24. Eli Siegel, Art As Gaiety (New York: The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, No. 851, 1989).

25. Jean Lipman with Margaret Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), 53.

26. Eli Siegel, Aesthetic Realism class, 1975