By Eli Siegel

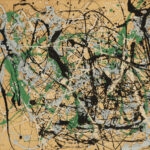

This groundbreaking essay by Eli Siegel was first published in December 1955 by theTerrain Gallery. November 11, 2015 it was reprinted in Sotheby’s catalog for its New York Contemporary Art Evening Auction to accompany Jackson Pollock’s Number 17, 1949:

Thoughts about a phrase from the Critical Writing of Stuart Preston on Jackson Pollock, New York Times, December 4, 1955: No use looking for “beauty” . . .

1. There is a contemporaneous distrust of the word ‘beauty’ which it is well to look into.

2. There is a feeling prevalent that while the word beauty might have been all right with the Greeks or in the Eighteenth Century or with the Pre-Raphaelites, we are beyond this; we are too tough for this, too modern.

3. It is felt that the unconscious working on, say, bits of paper, or a heap of broken brick or dishes in a sink, will get to art, perhaps, that is not beautiful as past art has been; even so, there is no reason why one can’t or shouldn’t take broken brick as a subject, or scraps of paper: art really doesn’t mind, nor beauty, either.

4. The unconscious when it is completely unrestrained, untrammeled is opposed by critics to the idea of beauty, if not to that of impact, or of power, or of the elemental.

5. However, the aesthetic unconscious, if looked into, goes just as much for beauty in the primary, continuing, and still fresh sense as the conscious does.

6. The unconscious, as artistic, goes after unrestraint, but unrestraint as accurate; and when unrestraint is accurate, the effect on mind is still that of beauty.

7. No matter how unrestrained, elemental, untrammeled, without ‘forethought’ Jackson Pollock is, or anyone else—if his work is successful, there is in this work power and calm, intensity and rightness, unrestraint and accuracy—and these, felt at once, make for beauty.

8. Because beauty has taken new forms, used material foreign to Veronese, Gainsborough, Ingres, Ryder, there is a disposition on the part of critics like Stuart Preston to think the word beauty is no longer alive and electrical.

9. It is alive; it stands for life at its liveliest, at the most free and the most true.

10. For example, the question comes up: What makes Jackson Pollock’s unrestrained unconscious, ‘elemental and largely subconscious promptings,’ better than somebody else’s unrestrained unconscious and ‘subconscious promptings’?

11. For everybody has an unconscious—very often unrestrained—and everybody has ‘subconscious promptings.’

12. The question for Mr. Preston and others is: What makes the unconscious or subconscious of Mr. Pollock, and the working without ‘forethought’ of Mr. Pollock, better, more artistic, more commendable in result than similar things of the mind in so, so many others?

13. It is the presence of some rightness, fitness, structure, purpose, composition, design or whatever you wish to call it in Mr. Pollock—at least if you see his work as art, that is what you see in it besides the ‘subconscious,’ the ‘promptings,’ the ‘elemental.’

14. If Mr. Pollock’s unconscious is artistically successful, it is because there is a logic in it, a rightness or knowingness; words of Mr. Preston himself, like ‘apparently aimless’ imply some such thing—just look at the apparently!

15. So we have spontaneity, elementalness, freedom, ardor in Mr. Pollock, and rightness, accuracy, logic, design, effect, too.

16. Spontaneity and rightness, intensity and accuracy are what we find in Delacroix, Bosch, Turner, Van Gogh, and—yes, Piero della Francesca.

17. Spontaneity and rightness seen in a work of art, make one feel it has form.

18. Form is a word still synonymous with beauty.

19. Beauty can be regarded as the apprehended presence of individual impetus and universal rightness, of unconscious and conscious—and at its best, the apprehended presence of the utmost spontaneity with the utmost truthfulness, rightness.

20. However, unrestrained Mr. Pollock’s unconscious is, it is going after design.

21. Otherwise, as was said (and it cannot be said too often) Mr. Pollock’s ‘abandonment of forethought’ would be like the lack of ‘forethought’ we find anywhere, with people not particularly artistic—and there is a mighty lot of ‘subconscious promptings’ in family squabbles, in sick rooms, in dull tavern brawls, in financial controversies.

22. People live differently today, but life goes on: the word life is as good as ever.

23. People go after beauty differently (for example, Jackson Pollock), but beauty is still around; the word beauty is as good as ever.

24. Mr. Preston in his effort to be desperately contemporary, has forgot to be deeply, vitally continuous—has forgot to be elemental in the very best sense.