By Barbara Spetly McClung

I love Mary Cassatt’s painting of 1893 titled The Child’s Bath.

Why this painting is beautiful, and what it can teach us are explained by Eli Siegel’s historic principle “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Mary Cassatt, through her subject matter and technique, shows the beautiful relation of intimacy and width that parents and children are hoping for in order to truly care for one another.

This lovely work answers one of the largest questions every mother has, which Aesthetic Realism makes clear and explains: How will we use our child—to make a separate world of our own, just the two of us, or to feel that through a child we are closer to the whole world?

In The Multitudinous Realism of Beauty, Eli Siegel writes:

“The beauty in a mother’s liking a baby is in her seeming to like reality even as she holds her own baby; the baby, at that time, is an example of what is ourselves and what is not ourselves, the proximate and the remote, acting as one.”

Mary Cassatt has painted a mother with a child very proximate, sitting on her lap at bath time. It is an intimate moment. The mother’s left arm secures the child firmly; but there is no clutching. It is a kind embrace. A soft towel is wrapped about the child at the waist, and Cassatt shows the line of the mother’s fingers continued by the folds of the white cloth—her embrace is continued and completed by an object in the world.

Mary Cassatt has painted a mother with a child very proximate, sitting on her lap at bath time. It is an intimate moment. The mother’s left arm secures the child firmly; but there is no clutching. It is a kind embrace. A soft towel is wrapped about the child at the waist, and Cassatt shows the line of the mother’s fingers continued by the folds of the white cloth—her embrace is continued and completed by an object in the world.

As she washes the child’s feet in a porcelain bowl, her right hand seems gently to guide the child’s right foot—but the touch of mother and child is mingled with the touch of water, and that upright pitcher seems to look on with interest. While mother and child are snugly in the same confined space, they are not gazing at each other; their eyes direct us to that basin of water. And as the mother bathes her child, both together are bathed in a bright, universal light—a light both warm and cool.

In his lecture Mind and Mothers, Eli Siegel speaks in a way I love about the job of every mother: “The first thing that a mother should do is see herself and the child in relation to everything. But that’s hard, complicated.” And he says a mother can feel: “You have the child near you and life is complete.”

This describes so well the two ways of seeing I had when my daughter was a few months old. During the day, as my husband was at work, I liked taking a nap with her on our bed, just the two of us. But often at night I would dream that she was falling off the bed, and I would wake up terrified, and grabbing for her at the foot of the bed. I spoke about this recurring dream in a professional class for Aesthetic Realism consultants and associates, and Ellen Reiss, the Chair of Education, asked me: “How do you feel as you are on the bed with Jennifer? Do you think it’s the thing you like most in the world?” I said yes and began to see that there was a way, at these times, that I was using being with my daughter to shut out the rest of the world.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that our purpose with any person—a child, spouse, friend—should be to see meaning in the outside world, not to exclude the world. Ms. Reiss said to me: “You have to see the beauty of using your child to like the world.” My husband, Dan McClung, and I have been learning these years what it means to use our daughter to see meaning in, and to like the whole world. I believe this painting is a beautiful guide for that.

Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal; or, Geometry in an Embrace

I’ve learned from Aesthetic Realism that we can ask ourselves this important question as we share a private moment with another person: “Is the whole world present?” In his book Self and World Eli Siegel writes about the meaning of the vertical and horizontal: “The vertical line is a symbol to the unconscious of the self alone; the horizontal, of the self going out.”

I’ve learned from Aesthetic Realism that we can ask ourselves this important question as we share a private moment with another person: “Is the whole world present?” In his book Self and World Eli Siegel writes about the meaning of the vertical and horizontal: “The vertical line is a symbol to the unconscious of the self alone; the horizontal, of the self going out.”

Both directions are here. We see the vertical in the positioning of both figures, in the stripes of the mother’s right sleeve, the child’s left leg, and in the pitcher. Then there are the soft horizontal lines of the dresser and the baseboard behind the mother that go out beyond the vertical format of the canvas. So while there is a feeling of particularity and of two selves alone, there also is a “going out.” Did Mary Cassatt feel, and also want us to feel, this mother and child are related to objects close to them and to what is beyond what we see here?

We also have the diagonal, which is a oneness of vertical and horizontal, and is very important in the composition of the painting. There are two strong diagonals—one formed by the stripes of the mother’s lap and skirt extending across the width of the painting, and the other by the little pink body, leg and toes. These diagonals cross in the very center of the painting!

In his book Mary Cassatt, Oils and Pastels, E. John Bullard has this description: ‘The oval created by their adjacent heads—

—repeats the round basin below;

—the two shapes are connected by the diagonal formed by the child’s arm and leg.”

When two heads make an oval, and a porcelain bowl has an oval, the bowl becomes more personal, and the heads more abstract. The personal and impersonal are joined by that oval shape.

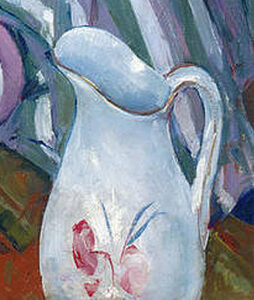

And look at the roundness of the belly of the child. Isn’t it like the roundness of the porcelain pitcher? The bend and curve of the child’s left arm is also like the curve of the handle of the pitcher. Cassatt shows there are softness and hardness in both the child and a porcelain pitcher.

And look at the roundness of the belly of the child. Isn’t it like the roundness of the porcelain pitcher? The bend and curve of the child’s left arm is also like the curve of the handle of the pitcher. Cassatt shows there are softness and hardness in both the child and a porcelain pitcher.

We see a concentration and expansiveness of thought, too, that is very moving. Aesthetic Realism Consultant and artist Dorothy Koppelman described in a paper she wrote on Mary Cassatt, how mother and child are studying feet together. “Intimacy and the world with form are here as two little feet are tenderly placed, looked at and painted in a circular tub of wash water in a bedroom.” There isn’t a cloyingly cozy feeling that can sometimes be as a mother holds her child, with a feeling of consolation—“I have you, I don’t need anything else.” There are inquiry and wonder as a mother and child observe that universal substance—water.

I have been so moved watching children playing in and with water. Children love to put their hands underneath a running faucet or splash the water around as they sit in the tub, to see what shapes it takes and how it feels. In these years, through knowing my daughter and her perceptions of and responses to the things she meets, I’ve come to see the world with more mystery and excitement. I’ve seen newly the wonder in a leaf on a pavement; constancy and change in the moon and the many shapes it becomes, and the thrill of meeting the softness and form of newly fallen snow. And what I have seen through her eyes, had me see freshly and respect more the elementary school students I taught.

We Are Related to the World

In Mind and Mothers Eli Siegel says that as a mother is very close to her child,

“she should see that what she is close to has come from a universe tremendously big, tremendously wonderful, though that universe was in her body. She should see the child in two ways: yes, that is her child—she is a mother, but the child likewise represents all the forces of the world, the force that makes Niagara, the force that makes daffodils, the force that makes a grass blade grow. When she is able to put together the fact that, as she is herself and a representative of everything, so the child is of her and yet is a representative of everything—then she is a complete mother.”

The way Mary Cassatt shows technically how this mother and child are related to the whole world is thrilling and gives this painting a tremendous meaning we can learn from. Mary Cassatt relates them through form, line and color to each other and to all that is around them. The background and foreground of the painting are energetic and vivid.

From the bold geometric patterns of the rug, to the floral wallpaper to the chest of drawers with bright flowers painted on it, you feel these two people are in the midst of a lively world. The olive green color in the stripes of the woman’s dress is similar to the color on the chest of drawers, the leaves in the wallpaper and the diamond shapes on the rug. The lavender and white stripes of the mother’s dress are also in the porcelain bowl. And the water has the same lavender color. The rosy red color in the lips and cheeks of mother and child are in the color of the rug and the flowers on that porcelain pitcher.

I love that pitcher. It looks on playfully and almost seems to be inquiring along with mother and child. It also has great mystery. We see the brightly painted exterior of the pitcher, but we don’t see its bottom.

And as we follow the stripes in the woman’s dress off the canvas, that pitcher brings us back into the painting. Without the pitcher there is a more enclosed atmosphere. I feel it is like a third person present, representing the outside world this mother and child were born to be fair to.

Studying this painting I have even more conviction that it is the whole world a mother and child are in, and which they want to love as they are together—walking down a street, reading a book, grocery shopping, or taking a bath. Eli Siegel and Aesthetic Realism show grandly how what is in every work of art has the means for knowing and answering beautifully the questions of our lives.

Barbara Spetly McClung taught in New York Public schools for many years. She and her husband Dan McClung are Aesthetic Realism Associates and have presented talks in the Terrain Gallery series “Art Answers the Questions of Your Life.” And with sociologist and Aesthetic Realism consultant Devorah Tarrow, she’s conducted workshops at schools & conferences on “Harriet Tubman, the Underground Railroad, the Cause of Slavery, & Us!”