By Carrie Wilson

In elementary school I loved studying the pyramids—the way they rose from that wide base to that pointed top, so grandly and mysteriously, out of the sands of Egypt.

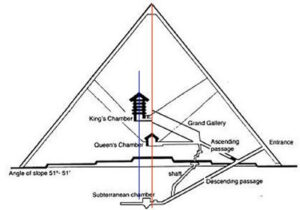

I remember drawing a copy of a cut-away cross-section of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza. The shape thrilled me, as did the diagonal corridors leading down to the secret inner chambers of the King and Queen. And I delighted in painstakingly copying the many blocks which made up this massive structure. The pyramid of the pharaoh Khufu, or Cheops, (the largest one, in the center), sits on a base of 13 square acres.

I remember drawing a copy of a cut-away cross-section of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza. The shape thrilled me, as did the diagonal corridors leading down to the secret inner chambers of the King and Queen. And I delighted in painstakingly copying the many blocks which made up this massive structure. The pyramid of the pharaoh Khufu, or Cheops, (the largest one, in the center), sits on a base of 13 square acres.

The average weight of each block of limestone is two and a half tons. Its total weight is six and a half million tons, and sheathed originally in gleaming white limestone, it rose 481 feet to a vanishing point in the blue sky.

I didn’t know that the reason I loved the pyramids was because they did what I wanted to do—that what people for four thousand years and more have wanted, is expressed in their form.

In his book The Opposites Theory, Eli Siegel writes:

Heaviness and lightness exist as one in the Pyramids. The fact that the Pyramids are exceedingly material, ponderous, stocky makes them heavy; the fact that they come gracefully to a point makes them light….Yet one feels the heaviness and lightness not at separate moments, but at one moment.

That is what I wanted to feel myself. I could be very ebullient, even giddy, as a child, and at other moments so doleful that my English father would sometimes remark jestingly, “Cheer up Kid, you’ll soon be dead.” These two moods in me were very separate, and continued to be until I began to study Aesthetic Realism and to learn what Eli Siegel is the first person ever to have explained: “The resolution of conflict in self is like the making one of opposites in art.”

I. The Fight between Seriousness and Lightheartedness Went On

Though I did well in school, the idea of serious study seemed like slavery to me. The most frequent criticism my father gave me when I was in high school was that I needed discipline. He got me a book called How to Study, and no present could have been less welcome. In college, I remember reading an assigned text called The Psychology of Learning, and every half hour having to get up and run back and forth in the halls. Often, if a man asked me out, I put my studies aside. Although I had a lively interest in many things, I couldn’t have said I was seriously interested in anything. This worried me, but I saw no way for it to change.

I liked to annotate my books with droll figures and comments. On a page in the index of a book by a famous art historian, I wrote a made-up title for a painting, “Still Life with Yo-Yo,” and did a drawing of my right foot. Yet, scrawled at the bottom, is the rather serious, self-critical statement: “About halfway through the book I begin to think that maybe he’s right to have given such a lot of attention to the Dutch and Flemish.”

I also liked to make fun of men, whom I saw as “fair game.” Yet in the flyleaf of the same book is the draft of an unfinished note to a man, which reads: “I feel so badly at not being able to give you the love I know you deserve.” I felt this about other men with whom I tried to have a serious relationship, and wondered despairingly what was wrong with me. The reason for my trouble is explained by Ellen Reiss in what she writes in her commentary to issue #1694 of The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known:

[W]hen we don’t want to value the world around us, we pay a price: through robbing things of their meaning, through making them unsubstantial, we come to feel our lives are empty. We also feel heavy—because there is nothing more burdensome than the false weight of conceit: the concentration on ourselves, the being laden with ourselves, and not wanting to see that we are related to everything.

I remember a joke I made in my junior year in college: “I’m just going to sit here and watch the world revolve around me.” I thought it was very clever, but as I said it, I felt hollow. I would have spent my whole life unable to feel my heart and mind was wholly given to anything had I not had the enormous good fortune to meet and study Aesthetic Realism.

In a class Eli Siegel asked me, “Do you think reality matters?” “Yes,” I said. And he asked, “Which is desired more by you, more seeing of reality, or more mockery?” I didn’t know: “You have trouble on the subject,” he said. Though I had suffered, I’d never realized the way I mocked and made light of things was against my being able to like the way I saw the world and people. With humor and compassionate conviction, he continued,

Any person who doesn’t hope that reality means more and more and more is a bourgeois dope. Anyone can feel unfaithful to what is dearest to one. There’s something in every person that stands for art and truth, and a part that stands only for self—and the battle is waged every day. We bow to truth and then we feel we’ve deprived self.

Mr. Siegel took my desires and worries, and my possibilities for valuable thought and expression, with a seriousness I had never met before, and certainly never had myself. Because he did, and because he taught that the more truly we know the world the more we’ll be able honestly to like it, I have the ability I once despaired of, to enjoy thinking about other things and people in a sustained way—about my husband, composer Edward Green, his life and his work; about the hopes and concerns of my friends; the lives of the persons I teach in Aesthetic Realism consultations; about music and art; and about justice to people everywhere. This is a change I am grateful for every day.

II. “A False Lightness Makes for a Real Heaviness of Heart”

That statement of Mr. Siegel, speaking in a class to me, was true of Alice Carter, a student of art. In Aesthetic Realism consultations, she’d been learning how, like every person, she was trying to put opposites together. When we asked what concerned her most, she said,

Alice Carter: I can go from being silly or light in a way that’s excessive, and then be very—well, what I’ve felt is serious. I don’t have the best relation of the two, and I would like to understand why.

This had come up, she told us, at her job with a manufacturer of lighting fixtures. Her office manager, Kathy Hamer, she told us, “joked a lot.” “I would laugh,” Ms. Carter said, “but there was something constant going on. I felt I didn’t like myself for it, and I wasn’t encouraging Kathy.”

Consultants: So you take the product seriously—light: you try to make light of everything.

Ms. Carter laughed. “Did you feel good when you laughed then?” we asked. “Yes,” she said.

Cons: Why, do you think?

AC: I saw something new from it, a relation between two meanings for light.

Cons: So there was more meaning felt?

AC: Yes, there was.

Cons: Humor can be beautiful. But do you think the trouble in this joking you’re concerned about is that there was contempt?

AC: I do.

Cons: There can be a great deal of frivolity because one doesn’t feel deeply light. All the gags that were said in schools and offices today, the wise cracks and giggles, do you think it is because people like the world and themselves, or because they don’t?

AC: Because they don’t.

Cons: Do you think, along with mocking, Ms. Hamer has a desire to reverence things?

AC: Yes, I do.

Cons: As you think of her, is that how you see her—as a person who’s trying to put opposites together?

AC: No, I don’t feel I’ve seen her that way.

We’ve learned that to take a person seriously means to see how the opposites of the world are in them, and as we do, a concern that seemed burdensome, takes on a width, a clarity, a sense of meaningful form that brings with it a true lightness.

“Seriousness and lightness are opposites that are one in reality,” we said. “For instance, do you think the blue color of your blouse is bright and deep at once?”

AC: Yes, it is.

Cons: Color is always a study in both. But when we want to have contempt, all the opposites are askew, and these very much. A person just feels she can’t stop herself from giggling, and then she’s weighed down. When Ms. Hamer is making jokes and you’re coming back with yours, do you think in some way you’re both superior to everything, and is that the appeal?

AC: Yes.

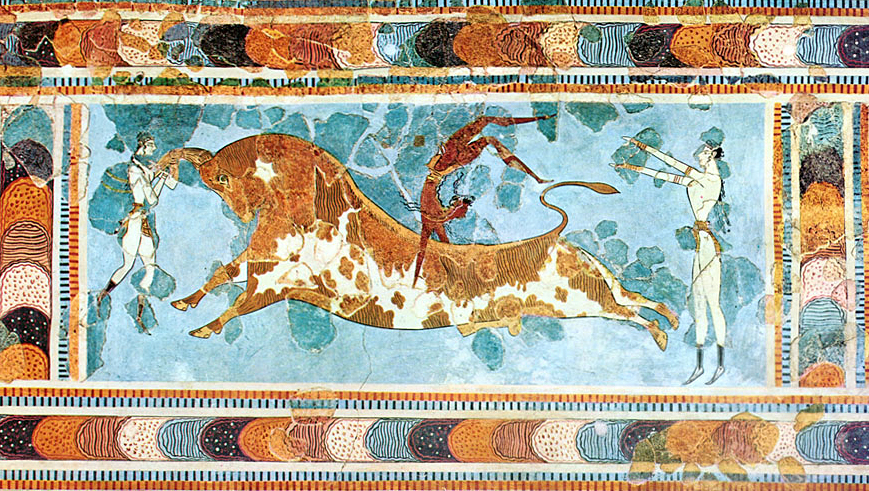

We looked then, in a book of art criticism we’d suggested she read, at this sentence by William Stevenson Smith comparing the art of Egypt and Crete:

In contrast to the timeless, static permanence of Egyptian statues, the instinct of the Cretan…was to catch an impression of movement and lively action.

(This is a Cretan fresco of three acrobats cavorting with a huge and rather merry bull)—

“What do you see in this sentence?” we asked Alice Carter.

AC: The opposites—the liveliness and something more immovable.

“You can study the opposites all through the history of art,” we said, “and they take different forms in different times.”

AC: This is exciting! I remember learning how many cultures affected the Egyptians, while their art has a style which was very different.

Cons: Do you want to be like the Egyptians, and be affected by many persons, or do you want to be sunk in the desert of your own ego?

AC: I want to be like the Egyptians. I’ve based too much of my life on not being affected, and I don’t feel it’s done me good.

Cons: Do you want to study how these opposites are together in the world?

AC: Yes, I do.

We gave her the assignment to write an instance every day of where she saw lightness and weight or seriousness in things, because as we see the opposites together in reality, they are more at one in our own minds. She wrote about the shadow of a tree, the rotating brush of a street cleaning truck, the ocean, her roommate’s quilt, and in their style her sentences put weight and lightness together. For example, she wrote:

Lightness and weight were one in the squirrel’s back and tail. The squirrel was jumping, away from me, towards the sun in Union Square Park. As it did this, the curve of its back and its lifted tail went up and down. This motion with the shape of the squirrel’s body put together heaviness and lightness.

And Ms. Carter told us:

I like the world more as I think about how lightness and heaviness are in the world and in people. The mocking Kathy and I encouraged in one another is not occurring. Our conversations are more thoughtful of other people and one another. I’m grateful to Aesthetic Realism that my thoughts can go towards this.

III. The Opposites in Art and in Ourselves

At a time when I was confused about what I wanted to do, Eli Siegel asked me, “Is there a conflict between the person who is lively and the person who is very serious, between lightsomeness and gravity, between the comedienne and the person who has to see life—all of it?” “Yes,” I said. And he continued, “Carrie Wilson sometimes feels like a bit of stone lost in the desert, and then occasionally feels merriment should sway everything. Are you capable of both?” “I definitely am,” I said. I felt so respected, that I was in his mind as I really was, and it enabled me to see myself more respectfully, with new understanding and clarity.

The opposites, I have seen, are both the one way to truly understand ourselves, or any person, and the one way to see what makes for the power and beauty of a work of art. “The state of mind making for art,” Mr. Siegel wrote, “is both heavier and lighter than that which is customary.” Let us look, for example, at a work of over 3000 years ago in Egypt.

Speaking in a class in 1977, Mr. Siegel asked:

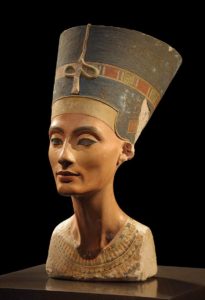

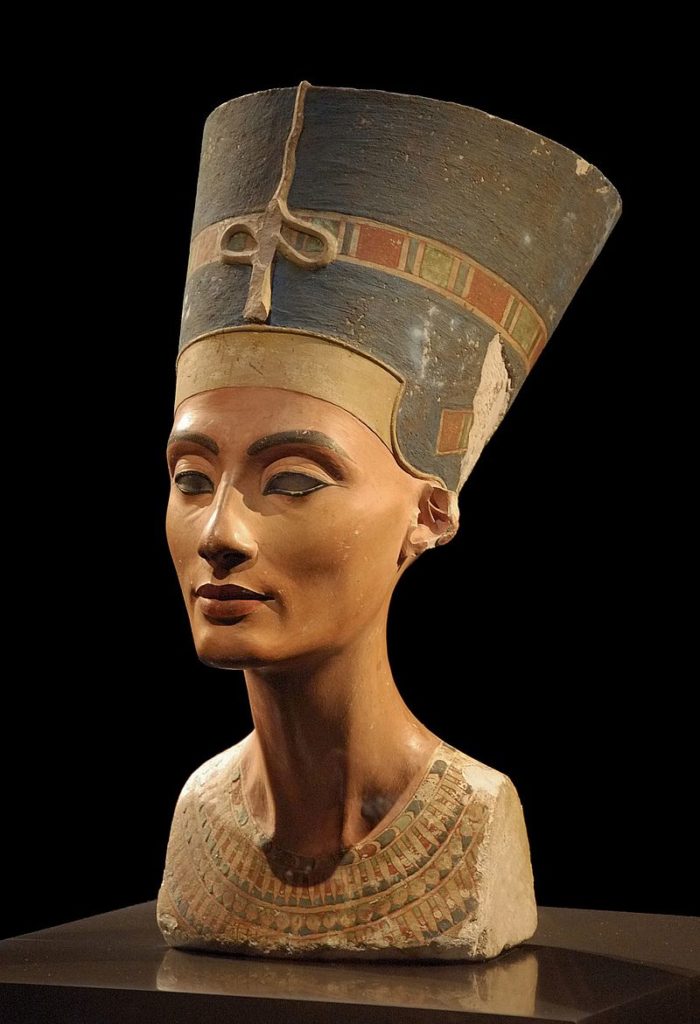

What is the value of the Egyptian point of view?—there are so many centuries in it. What does the Nefertiti portrait have? Severity and gaiety is what she stands for. She could be compared to the pyramids. Angles usually stand for severity.

These opposites are central in Egyptian art, as such, throughout its many centuries, with the accent earlier on severity, seriousness, weight (this is King Mycerinus and His Queen of about 2600 BC)—

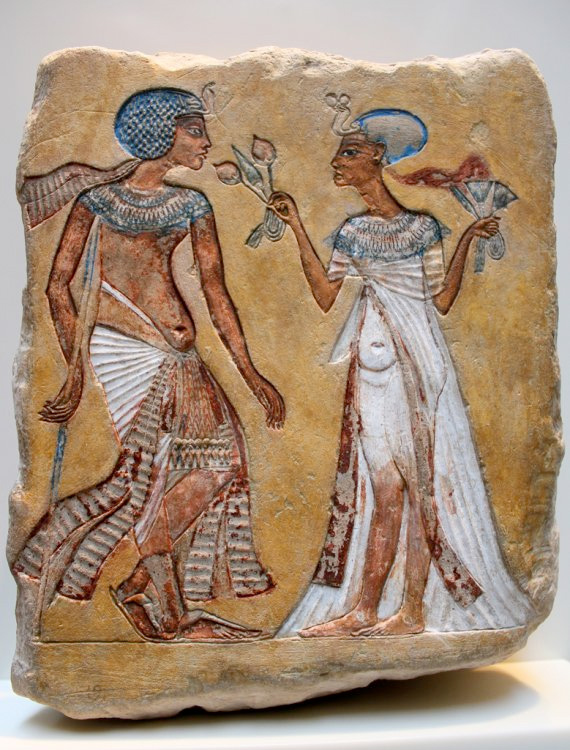

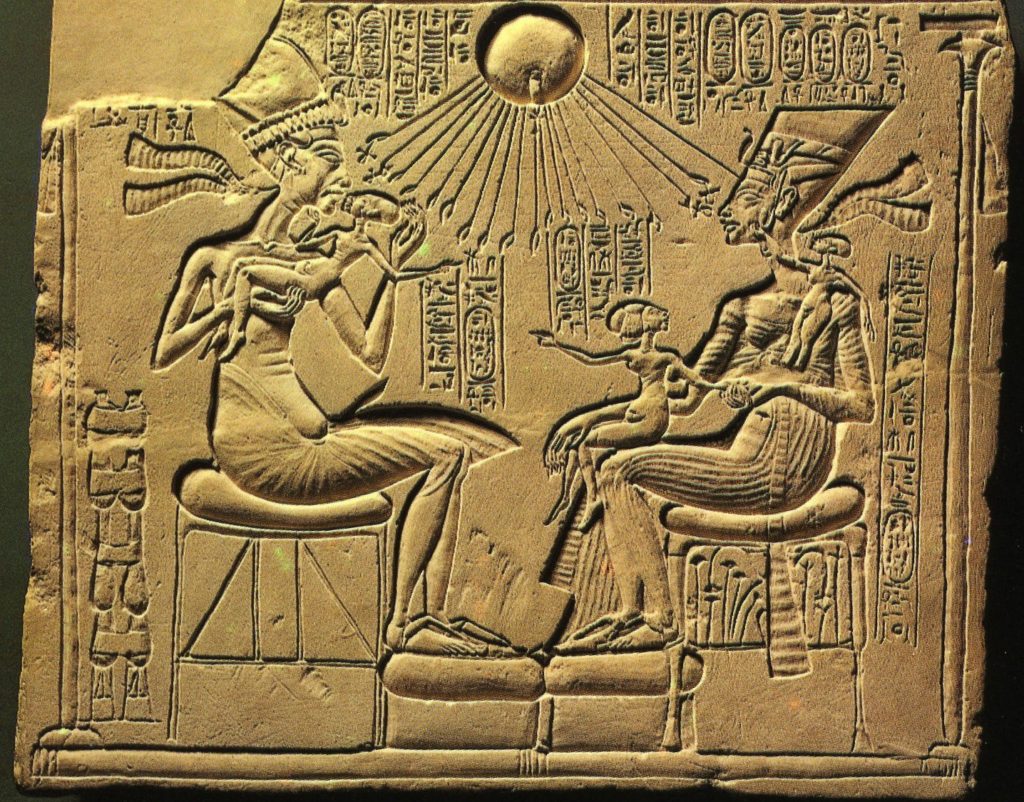

—and then, increasingly, culminating in what is known as the Amarna period, beginning in 1375 BC—the period from which this relief comes—taking on more lightsomeness, grace, warmth, and gaiety.

Mr. Siegel once said to me: “There is the use of the severe profile. Do you like to give a look that would show the other person his place?” I had. This is so different from the portrait of Nefertiti.

This painted limestone and plaster bust, discovered in the workshop of the chief sculptor Thutmose, and now one of the most famous portraits of women in the world, has a timelessness, a regal severity in those angular shapes and far-seeing eyes, yet she is warm, immediate. Her gently smiling lips are generous, full. She seems to see us and everything at once. Her regal headdress is continuous with the warmth of her face. Seen from the front there are many curves, while from the side, angles are accented.

Angles, as Mr. Siegel said, are on the side of severity, while curves are on the side of grace, lightsomeness. And see how every angle in this portrait is also a curve. The nape of her neck, her throat, chin, lips, the tip of her nose, the point of her curving brow, the peak of her headdress—straight as it rises, and curving at the top. Her beautiful profile is at once chiseled and gentle.

Angles, as Mr. Siegel said, are on the side of severity, while curves are on the side of grace, lightsomeness. And see how every angle in this portrait is also a curve. The nape of her neck, her throat, chin, lips, the tip of her nose, the point of her curving brow, the peak of her headdress—straight as it rises, and curving at the top. Her beautiful profile is at once chiseled and gentle.

Severity and exuberance are in the colors as well. Encircling her neck is a broad collar representing many-colored stones. Across her brow and around the back is a band, and the dark crown is encircled with bands of red, blue, green and gold. The eager, forward motion of her head is counterbalanced by that dark headdress, or crown, which—opposite to the pyramids in form—expands as it rises in that dramatic diagonal. This crown seems to represent the width and depth of her thought.

I believe that at the time this work was done, in the reign of Akhenaten, a greater like of the world was encouraged; there was more good will. In a lecture on H.G. Wells’ Outline of History, Mr. Siegel said that Akhenaten was:

One of the best monarchs of the time, one of the most interesting characters in all history…and it was his wife who was the famous Nefertiti….It seems he respected his wife very much, and she was a woman of depth and power….Wells writes about how he wanted to change the religion of Egypt, make it something larger, get away from some of the strange beings…

Akhenaten went against the power of the priesthood, which greatly relied on secrecy—the name of the chief god, Amun-Re, meant “The Secret One.” Akhenaten said there was one god, Aten, the sun, visible to and blessing all. He and Nefertiti moved the capital from Thebes and built a new city at Tel el Amarna, in which there seems to have been a greater democracy. This is a carving in limestone which shows them playing with three of their six daughters.

They wanted to be seen as human, accessible. The Oxford Companion to Art writes of Amarna Art:

In palace apartments and elsewhere themes from nature were depicted with great liveliness and sympathy, and intimate vignettes of royal domestic life were for the first time represented….Figures were more naturally posed, with some attempt to express emotion and individuality.

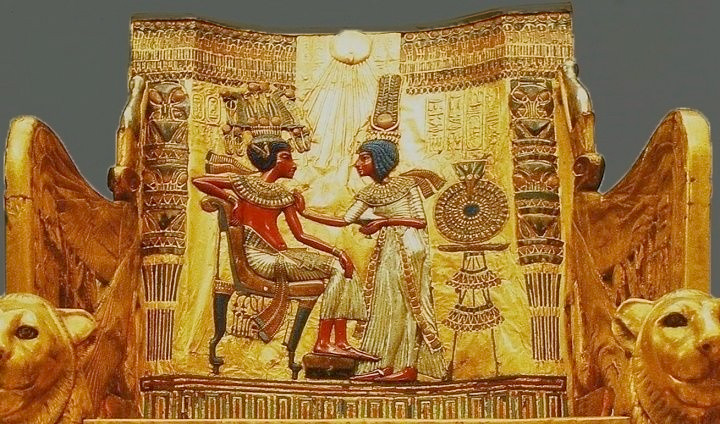

A scene which scholars believe depicts Akhenaten and Nefertiti appears on the back of a throne found in the tomb of Akhenaten’s son Tutankhamun.

This relief sculpture is formed of sheets of gold and silver, colored glass, glazed ceramic, and inlaid calcite. At the top center of this domestic scene is the brilliant disk of the sun, Aten, representing the source of life and the largest power in the world. Mr. Siegel once said to me in a discussion about love: “In every relation of two people, the world is there saying, ‘Boy and girl be fair to me.'” I am sure that one reason this scene has been loved is because it embodies this principle visually in a profound and delightful way.

The pharaoh, wearing an elaborate crown, colorful collar, and dancing sash, sits in profile, yet in an easy posture, while his wife tenderly approaches him, perhaps anointing him from a small bowl in her left hand. As her other hand kindly and thoughtfully touches his shoulder, the rays of the sun, Aten, descend between them. And see how each ray of the sun ends in an outstretched hand of blessing. We feel she is cooperating with the world to have good will for him, and that is something every person needs to learn from. They are not clutching each other, yet they are connected with tremendous force through the straight, horizontal line made by the serious gaze of their eyes across that golden space. And see how in that same line the graceful hands of Aten bridge the distance between them. Seriousness and lightness are inextricably together.

The pharaoh, wearing an elaborate crown, colorful collar, and dancing sash, sits in profile, yet in an easy posture, while his wife tenderly approaches him, perhaps anointing him from a small bowl in her left hand. As her other hand kindly and thoughtfully touches his shoulder, the rays of the sun, Aten, descend between them. And see how each ray of the sun ends in an outstretched hand of blessing. We feel she is cooperating with the world to have good will for him, and that is something every person needs to learn from. They are not clutching each other, yet they are connected with tremendous force through the straight, horizontal line made by the serious gaze of their eyes across that golden space. And see how in that same line the graceful hands of Aten bridge the distance between them. Seriousness and lightness are inextricably together.

Much more could be said about this work, but I see it as representing what Aesthetic Realism teaches, and every person deserves to learn: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”