By Donita Ellison

Presented at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Years ago as an art student in Missouri, I saw no relation between the work I would spend hours doing in the studio and the facts of my life, which like most people’s, were often confusing. I felt, on the one hand, there was art, and on the other there was my personal life with family, friends, at work and school—and I saw no relation whatsoever among them. That painful division changed when I began to study the Aesthetic Realism principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” I am proud to use this as my critical basis as a teacher of art. Today I am going to discuss some aspects of the work of four American artists, all realists who, in their individual ways, show that what is going on in art is a means of understanding the opposites in ourselves and the world we live in.

1. Repose and Energy

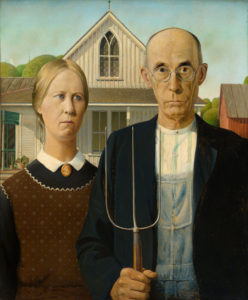

The Regionalist style of the 1920’s and ‘30’s, which included the work of Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry, celebrated the people of the American Midwest:

Thomas Hart Benton memorialized their history and life in his narrative murals, the work for which he is best known. When I first saw his murals in the Missouri State Capitol building, I was amazed by the scope of activity on those walls: he had so many figures, doing so many different things in one composition—politicians stumping in the town square; a mother diapering a baby; men hunting, cutting wood and plowing; farmers pitching hay and milking a cow; a woman rolling out biscuits dough.

Thomas Hart Benton is known for his sweeping energy, compositions teaming with motion, but he also has solid structure. At the Kansas City Art Institute he taught that a painting must have a “grand design.” But he also said he wanted to show what he described as the “pulse, go and come, rhythm” of life.

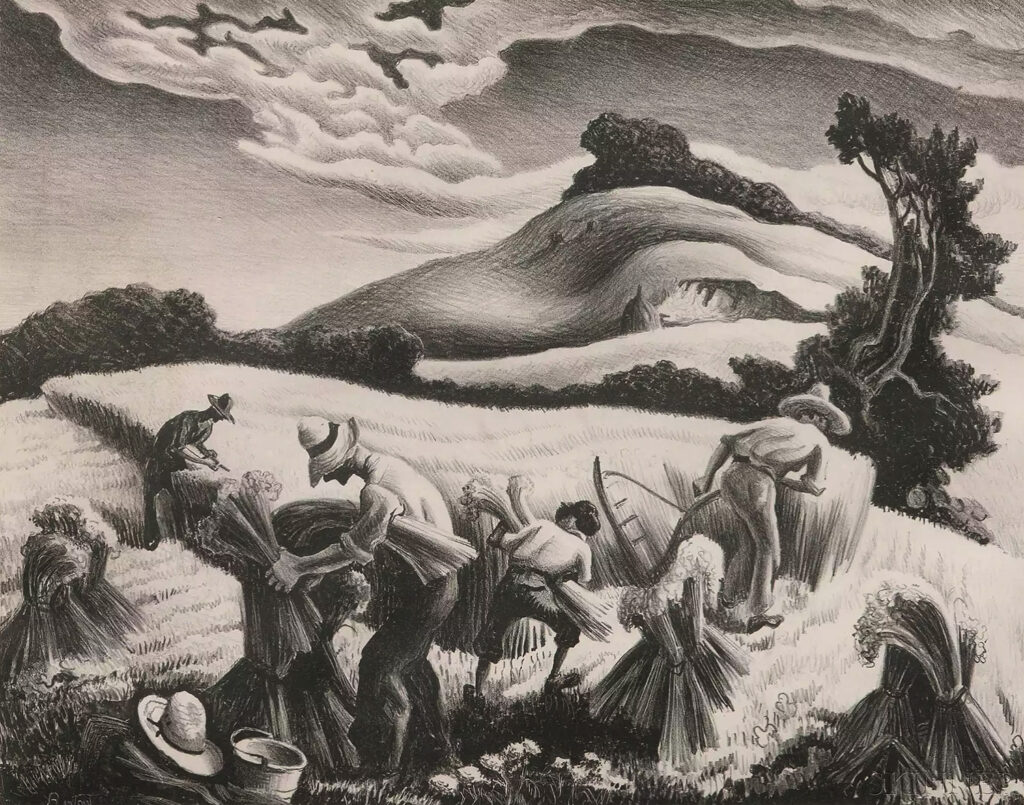

We see that in this 1939 lithograph titled “Cradling Wheat.”

In this scene, with its drama of black and white forms there is a dynamic energy that surges throughout the composition. Three men and a boy bend in their labor, they are separate, individual—but together their forms create a quick, tight rhythm as the diagonal lines and curves of their arms and backs, the stalks of wheat, the cutting scythe move, down, up, around—come forward and back. Together they create a sweeping curved line in the shape of a scythe that thrusts upward through that dark tree, joining earth, men, wheat and sky. The tree curves gracefully like the men and continues this upward momentum, culminating in an eddy of clouds stirring about, moving with the wind. Benton said of his work: “What I wanted to show was the energy and rush and confusion of American Life.” Benton’s largeness of vision and his sweeping energy are what influenced his most notable student, the abstract expressionist, Jackson Pollock.

Growing up in the heartland of Missouri, within 40 miles of Thomas Hart Benton’s birthplace, I saw the same Ozark hills and life that he depicted with such vitality. But much of the time I was bored, lethargic and often felt painfully separate from other people. Aesthetic Realism taught me that the cause of boredom isn’t that the world is dull and uninteresting, but that we get an importance in feeling that nothing is good enough to affect us. In an Aesthetic Realism consultation I was asked: “When you are bored, what happens to all great art, all the advances in science, to Michaelangelo, Shakespeare, Leonardo Da Vinci?” I had never thought of such a thing. I saw that I had been denying meaning to people and things and that was why I felt dull and empty. Art, Aesthetic Realism, teaches is the greatest opponent to contempt: the disposition “in every person to think we will be for ourselves by making less of the outside world.” An artist wants to see reality, not lessen it.

2. The Ordinary and the Strange

In his definition of Realism from “Definitions and Comment, Being a Description of the World” Eli Siegel writes:

“[T]he subject of all art, including realistic or naturalistic art, is the world as such…. True realism… in getting in the ordinary, somehow gets in the strange, too. To get in the ordinary and not the strange would not be realistic about the real world…”

The relation of bright sunlight and dark shadow in Benton’s undulating landscape makes for a feeling of strangeness.

The work of Bo Bartlett also deals with how strangeness is in what we see as ordinary. Compared to Benton’s energy, the paintings of Bartlett are more quiet and still. Large in scale, they depict the casualness of a moment, a homecoming celebration, a woman riding a bicycle, a girl on a tire swing. For subjects he often uses family and friends:

These images are, at the same instant, straightforward and strange. As Bartlett stated in an interview, they “aren’t simply portraits,” but “visual metaphors,” that “evoke a more complex interpretation and response.” He places the horizon almost at the bottom of the composition, creating a somewhat surreal landscape that recedes into great depth, yet is mostly sky. And his large figures in the foreground, set against that wide, expansive sky, usually have fixed yet intense expressions that suggest inward turbulence. What is the relation of these individuals with their perplexing inner thoughts to that distant horizon and all that space?

Let’s look at the title painting of the exhibition, “Heartland.” Slightly over five by seven feet, its very scale shows that Bartlett feels this very ordinary American scene, a boy with a red wagon, has large meaning. And there is something surprisingly unsettling.

Dressed in a red t-shirt and rolled up jeans, the boy stands casually, looking straight at us with a firm, somewhat troubled and angry expression. But his diagonal stance, with his hand on his heart has yearning. He seems to be asking something from us. Is he asking for us to know him, and to see how he is related to the world of specific objects and all space and time?

Visually this is what the painting does. He is joined to the wagon by the energetic black diagonal line of its handle. The vertical form of his shirt has the same intense red as the horizontal form of the wagon. He has two white socks and red shoes, and the wagon stands on white and red wheels. His rising form joins earth and sky. The wagon carries a load of dark reddish tangled sticks that have mystery and reach out like filaments into space. And that space beyond, with its imperceptible fusions of delicate pinks, yellows, blues, also has something a little disquieting. Is this boy saying, “I have the subtlety, vagueness, disorder, confusions, the mystery and space of the world in me too”? I think he is and with his hand on his heart he seems to be asking with earnest feeling that we see it.

3. Universe and Object

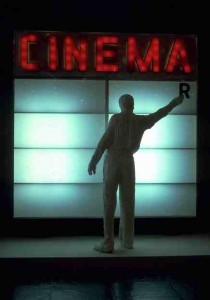

In the 1960s Realism took a new turn with the advent of Pop Art. Artists such as Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, George Segal, Roy Lichtenstein, took popular images found in advertising, newspapers, and movies, as well as commonplace objects and dignified them as subjects of fine art (click on images to get larger size):

The Pop Art sculpture of Claes Oldenburg challenges our confined notions of objects that we use without really “seeing” them. Oldenburg makes hard things soft, small things large, and turns things upside down—all to make us see them with more power and respect:

How many times have we really studied the form of the cake that we devoured with great pleasure? And how many times have we used an object like an eraser only to put it aside without a second thought? When we are confronted by his 19 foot high eraser, or a 6 foot wide slice of cake, ordinary and humble objects take on surprise, strangeness, grandeur. Do objects, like people, deserve to be seen in all their relation and mystery? Oldenburg said he wanted to have people recognize the “power of objects.”

Let’s look at this domestic object, the clothespin. In “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites,” Eli Siegel asks this question about opposites which are central in Pop Art and this work of Oldenburg: “Universe and Object:

“Does every work of art have a certain precision about something, a certain concentrated exactness, a quality of particular existence?—and does every work of art, nevertheless, present in some fashion the meaning of the whole universe, something suggestive of wide existence, something that has an unbounded significance beyond the particular?”

Oldenburg’s “Clothespin,” standing at 15th and Market Streets in Philadelphia, is definitely a clothespin; you couldn’t mistake it for anything else. Yet in its soaring height of 45 feet it has an “unbounded significance beyond the particular.” Its simplicity and monumentality has a dignity beyond the domestic. The world that has tension and ease, dark and bright, is here. Its dark sides curve upward with elegant ease where they are joined by a bright steel clip. There is just enough tension between the two sides at the base for the clothespin to open ever so slightly at the top. As everyone knows, a clothespin without that tension is useless, and without it this sculpture would also lack life. Incidentally, I think the artist saw that, in silhouette, the two sides of the clothespin resemble a couple embracing—this has both humor and romance.

The opposites of strength and delicacy, open and closed are also here. Manufactured of black cortan steel, the clothespin stands firmly upright almost like a dancer on point, balancing at the place it’s most vulnerable, where the two sides at the bottom are the most open and thin, while the top opens to receive the surrounding space. Here is the clothespin at night seen in relation to Philadelphia’s City Hall building.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that wanting to know what a thing is and how it is related to all other things is good will— “the desire to have something else stronger and more beautiful, for this desire makes oneself stronger and more beautiful.” This is the purpose of all art, and that of Claes Oldenburg when he said: “Some things I am attracted to do not seem to be liked enough. By choosing to remake them, I may help them. I wish the best for all things.”

4. Art Is Against Contempt

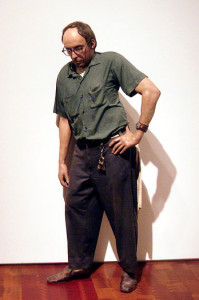

In 1999, while viewing a Duane Hanson exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum, I, and likely hundreds of people had a wonderful and strange experience looking at his life-size superrealist sculptures of ordinary people—a janitor, a woman with a shopping cart, and a museum guard, of whom you were tempted to ask directions to the rest room.

You couldn’t help but think about who and what was an actual living person? Like Thomas Hart Benton decades before, Hanson wanted to show the meaning of ordinary people. And in his sculptures, with astounding verisimilitude, he reproduces—down to the minutest details—clothing, glasses, hair and accessories that include actual purses, brooms, shopping carts.

The Joslyn Art Museum of Omaha Nebraska stated that “Hanson’s eye on humanity was penetrating—he analyzed every detail that our postures, expressions, clothing, and accessories say about us.” Is the artist’s purpose in having a penetrating eye, different from how we can think we are very keen in seeing the flaws of people? It is. The purpose of an artist is to see with meaning and respect, which is utterly different from how we can look down with contempt, feel superior, quickly sum people up and in doing so rob them of their humanity.

5. Heaviness and Lightness

I think one of the most moving of Hanson’s works is the “Tourists” of 1970. One could easily have contempt for this couple in their mismatched apparel–he in plaid shorts and Hawaiian shirt, she in snugly fitting stretch pants, patchwork tote bag, thick plastic jewelry and head scarf. Yet, Hanson’s work is impelled, as all successful art is, by his seeing that within the mundane and ordinary, there is something, as Mr. Siegel said, “that has unbounded significance beyond the particular.” This is present in “Tourists” which is a beautiful oneness also of the opposites, heaviness and lightness, about which Eli Siegel asked:

“Is there in all art, and quite clearly in sculpture the presence of what makes for lightness, release, gaiety?—and is there the presence, too, of what makes for stability, solidity, seriousness?—and is the state of mind making for art both heavier and lighter than that which is customary?”

In this work there is a oneness of physical weight and wonder, and heaviness and lightness are in every detail. The man’s figure is stocky, yet the mixed patterns of his clothing are cheerful and have a lightness in the way they loosely hang. His camera equipment, hanging heavily around his neck, is supported by thin straps. The tight fitting clothes of the lady reveal the fullness of her body, yet her hips, so solid, are bright red and the hem of her pants jauntily lifts upward. And across her matronly breasts, thick and thin black and white horizontal stripes create a lively rhythm.

The stance of both is solid, yet the weight of their bodies is centered upon the space between their feet. That triangular space, as we saw in Oldenburg’s clothespin, seems to balance and lift their bodies. And weight is lifted too as they look upward with wonder—he with a steady gaze, lifts his hand to shield his eyes; and she with a slight tilt of the head, parts her lips in pleasure and awe. Something beyond has their attention: they are arrested, deeply affected by it, and we find ourselves looking up to them and with them.

In his lecture “Aesthetic Realism and People,” Eli Siegel explains why the knowing of people, which art can help us do, is so important for our lives. He said:

“We cannot afford to despise reality. If we do, we are giving ourselves poison. The important thing about people—with all their weaknesses, hypocrisies, mistakes, meannesses, lazinesses, grudginesses, inertias, pretenses—is, they are real….There is not a person who has ever lived who can’t tell us something about ourselves.”

Aesthetic Realism shows that what is going on in American art is a guide to learning about who we are, what the world is, and how to see it in the best way. “The depths,” wrote Eli Siegel, “the real depths, of self are the world. The further we know what these depths are, the further we know what reality is.” American art is for this.

Donita Ellison, originally of Springfield, Missouri, is a printmaker and sculptor who taught fine art for 18 years at LaGuardia High School for Music & Art and the Performing Arts, and is an Associate at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, both in New York City.