By Lore Mariano

From the moment I first saw them, I felt Jackson Pollock’s action paintings had something I was yearning for—something deeply composing and satisfying to me. I learned from Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy founded by Eli Siegel in 1941 and taught in New York City, that these paintings have something every person is looking for. Mr. Siegel, the person who understood beauty and the human self, stated: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

I learned from this principle why I was so taken with the paintings of Jackson Pollock: they put together opposites I desperately wanted to put together in myself.

In his landmark broadside, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, Mr. Siegel writes about Freedom and Order:

Does every instance of beauty in nature and beauty as the artist presents it have something unrestricted, unexpected, uncontrolled?—and does this beautiful thing in nature or beautiful thing coming from the artist’s mind have, too, something accurate, sensible, logically justifiable, which can be called order?

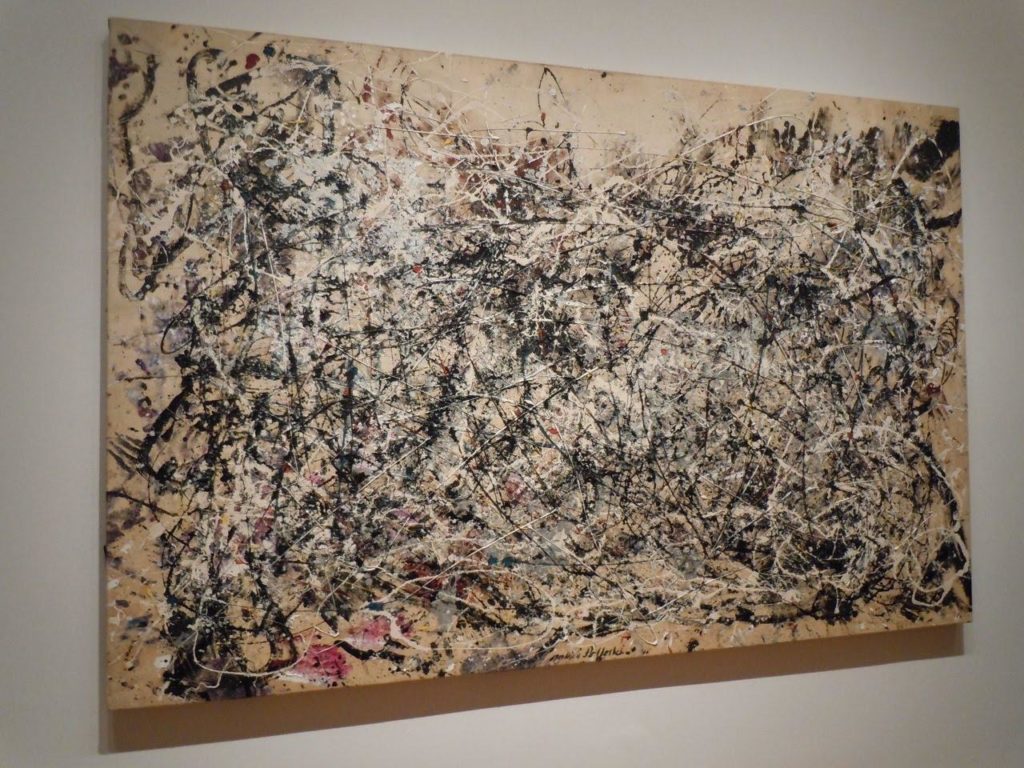

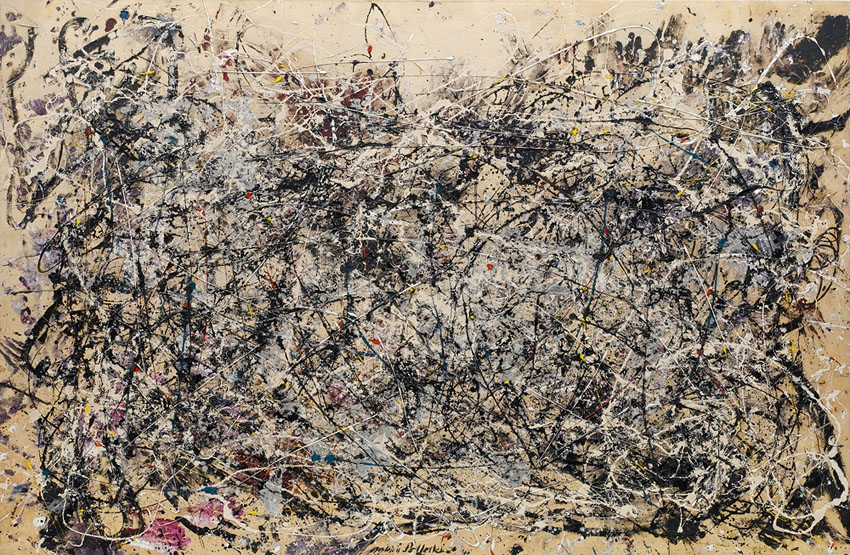

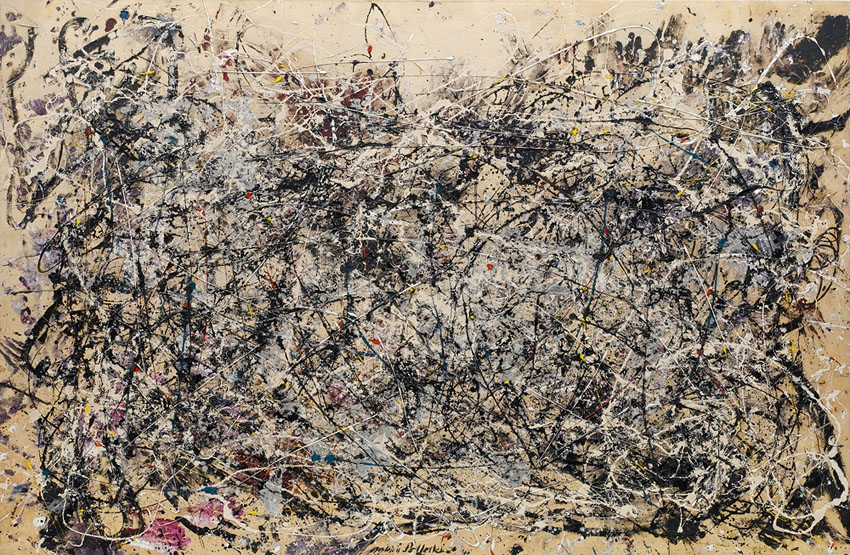

Jackson Pollock’s Number 1A, 1948 shows how much paint can be “unrestricted, unexpected, uncontrolled” as we see it poured onto a canvas making lines that are assertive, and we also see a complexity of shapes, globs, pools of paint layered one on top of another. Lines interweave, while remaining individually perceptible, distinct and free.

There is a tremendous speed in black and white lines laid over areas of paint; and there is the airiness of space in the bare canvas. Yet there is also strictness and economy in this work. One restriction Pollock imposed on himself was his use of colors that are restrained, even dignified—such as black, white, tan, and aluminum gray—and he shows by the way these dignified colors are poured and dripped that they can be wild. And all this he does within the borders of a large rectangular canvas 5’8″ by 8’8″. I think what Jackson Pollock did with paint is great.

1. I Wanted Freedom and Order

In an Aesthetic Realism class, Mr. Siegel spoke to my mother, Shirley Jones, a consultant with the trio The Later Surprise, about the opposites of freedom and order in me. He asked her, “Is your daughter [both] systematic and untamed?” This described me.

In high school, I liked the strict orderliness of boarding school and having every hour planned. But I went wild on the weekends—driving down the highway with blasting rock music on the radio. When I graduated, I felt at last all restrictions were lifted. But soon I was terrified of the way I was driven to feel “free”, including through using drugs. The wilder I was, the more desperate I was for order. At my wildest, I still spent summer afternoons and nights working double shifts as a nurse’s aid, where there was a routine and order I loved. I didn’t know how these opposites could be together in myself, and so I shuttled from one to the other.

In an Aesthetic Realism consultation, when my consultants asked me this kind question, first asked by Mr. Siegel: “What do you have most against yourself?,” I said “I’m impulsive sometimes—a lot of times.” I was very ashamed of this, and my consultants asked me:

Do you feel when you want to do something, you’ll do it no matter what the cost, just because it came into your mind—and no one can stop you?

I began to understand that the reason I felt bad about the way I was “free” was because it arose from having my way at the expense of what people and things deserved from me. Aesthetic Realism defines contempt as the “disposition in every person to think he will be for himself by making less of the outside world.” I learned the central cause of my pain arose from the hope to have contempt for the world-to get rid of obstructions I saw as in my way while flattening the depths of people.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that the deepest desire of every person is to like the world—to want to know it and be just to it. And as I saw more meaning in the world, I stopped trying to get away from it. I felt more truly free—at ease in the whole world because I was learning to see it fairly—and I stopped using drugs. We can learn from art that true freedom always arises from justice to reality!

2. Jackson Pollock’s Number 1A, 1948 Is Accurately Free

Jackson Pollock’s work has been seen as the epitome of freedom. Yet with all this great tumult, there is form. Look at the way the painting is held together by the four corners; there are black masses in each corner that contain everything in the painting, while the motion within is still pushing out.

Look at the vertical shape Jackson Pollock has made at the far left—almost a column composed of black paint and the space of the canvas. Our eyes go from left to right across the canvas and follow the shapes of the large curves. Our eyes are also taken across the canvas by a diagonal that begins at the lower left-hand corner and goes through the center to the upper right. There is a tightness and expansion, exactitude and width in the actions of the paint. Jackson Pollock’s Number 1A shows we don’t have to shuttle back and forth between order and freedom—in this painting they are one.

Throughout the painting, there are tiny, thick drips of brighter colors—red, yellow, orange and blue. There is a red dot just right of the center of the painting.

I remember cynically thinking before studying Aesthetic Realism, I was just a small dot in a vast, confusing world. But I also felt, like this dot, I was the one bright point in my family’s life. Aesthetic Realism taught me that the world outside of me is deeply my friend because it has an aesthetic structure we can honestly see as beautiful.

3. All Art Puts Together Opposites

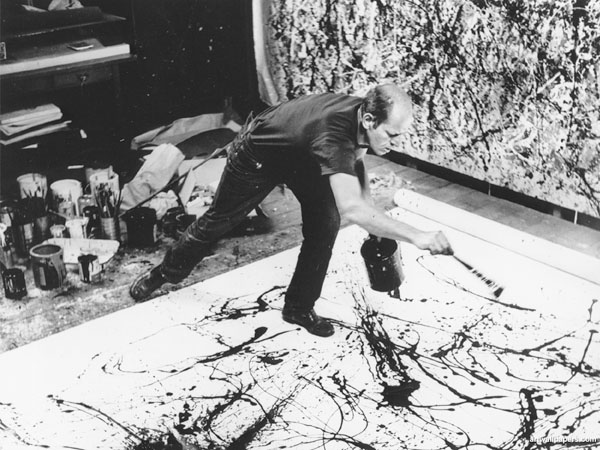

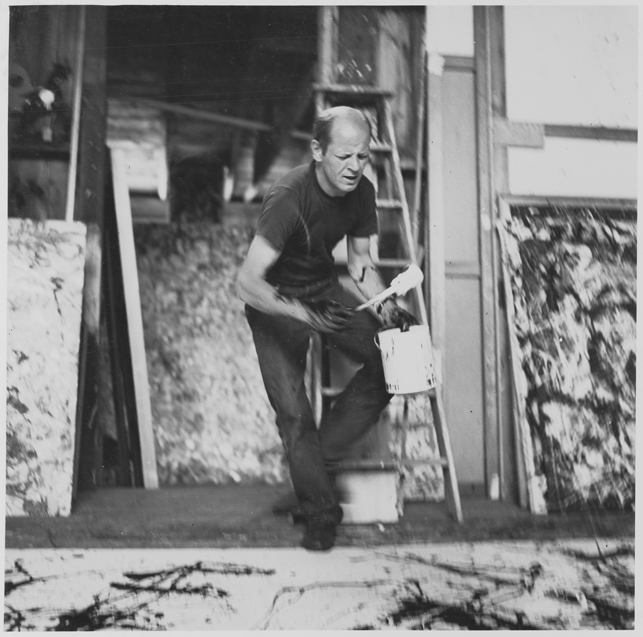

In his action paintings Jackson Pollock used paint in a completely new way. He put aside conventional methods and invented a new art form. Pollock said:

I continue to get further away from the usual painter’s tools such as easel, palette, brushes, etc. I prefer sticks, trowels, knives and dripping fluid paint or a heavy impasto with sand, broken glass and other foreign matter added.

As he worked, Jackson Pollock was systematic and untamed not at different times as we all can be, but at the same time. He found a rhythm in how paint was dripped, poured, spattered. He was studying the opposites sheer—freedom and order, oneness and manyness, speed and slowness, thick and thin. Frank O’Hara, in his book about Jackson Pollock, writes:

There has never been enough said about Pollock’s draftsmanship, that amazing ability to quicken a line by thinning it, to slow it by flooding, to elaborate that simplest of elements, the line—to change, to reinvigorate, to extend, to build up an embarrassment of riches in the mass by drawing alone.

In a film I saw of Jackson Pollock painting, I was struck by the way that he moved swiftly and gracefully around the canvas tacked to the floor as he poured and spattered paint.

Then, he would step back and judge, then move and paint again.

What looks like chance has logic and control at the same time. Jackson Pollock said:

When I am painting I have a general notion as to what I am about. I can control the flow of paint; there is no accident.

In an Aesthetic Realism class Mr. Siegel described the depth of emotion in Jackson Pollock as he painted, and why it matters. He said:

There does seem to be a kind of determination that was felt. With all the frantic activity on the floor there was a feeling he was really trying to get after what reality was like.

I believe Jackson Pollock wanted to see and show the world in its immensity when he painted, and this is what drew me to his paintings. I couldn’t sum-up, manage the world and have it on my own terms. They brought out something big and more respectful of the world in me as I looked at them.

The tragedy of Jackson Pollock’s life is in this statement of his: “Painting is no problem; the problem is what to do when you’re not painting.” He could have learned from Aesthetic Realism how to have the art way of seeing the world all the time. When he was painting he was happiest because, as Aesthetic Realism has described, he was “trying to get after what reality was like.”

Pollock said, “The painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.” What beautifully comes through in Number 1A, 1948 is a sense of the force of reality as tremendously free, and yet having subtle and mysterious order, accuracy and logic, too.

“The depths, the real depths of self are the world,” writes Mr. Siegel. And one of the things I love in this painting is how we see self and world as one in the way Jackson Pollock stamped his own hand prints in the upper right-hand corner of the painting—and we see something resembling two pink footprints in the lower left corner. The warmly touchable and the vast infinite are made one.

In “Beauty—and Jackson Pollock, Too,” Mr. Siegel writes:

No matter how unrestrained, elemental, untrammeled, without “forethought” Jackson Pollock is, or anyone else—if his work is successful, there is in this work power and calm, intensity and rightness, unrestraint and accuracy—and these, felt as one, make for beauty.

Aesthetic Realism explained the relation of world, art, and the self truly—and I am everlastingly thankful to it for giving me the means of looking at a work of Jackson Pollock, studying what makes it beautiful, and enabling me to learn so deeply about my own life and what I am hoping for from art.

Lore Mariano is a Legal Technology Training Manager, and Aesthetic Realism Associate. Her talk was originally given in the historic Terrain Gallery series titled “Aesthetic Realism Shows How Art Answers the Questions of Your Life!”