By Barbara Spetly McClung

When I began to study Aesthetic Realism, I knew for the first time in my life that what I felt inside, to myself, could honestly go together with what I showed on the outside. I didn’t have to hide any more. I love this Aesthetic Realism principle stated by Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Through studying this great principle I have a life I can truly respect myself for. And it explains why I was swept by Matisse’s The Blue Window from the moment I saw it.

Matisse has painted a view from inside a room—the bedroom of his house at Issy-les-Moulineaux—looking out to the garden, his studio, and the sky beyond. Opposites that were so painfully divided in me—inside and outside—are shown by Matisse to be one in a way that is mysterious, beautiful, and often humorous. One of the first things I noticed studying this painting was that where the inside ends and the outside begins is not clear. “This is great,” I said to myself, and I wanted to know what Matisse had done.

The Blue Window shows a beautiful relation of inside and outside. As I studied this work, I was affected to learn about why Matisse liked painting the motif of the window. In the book Matisse in the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, the author John Elderfield quotes Matisse as saying:

The Blue Window shows a beautiful relation of inside and outside. As I studied this work, I was affected to learn about why Matisse liked painting the motif of the window. In the book Matisse in the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, the author John Elderfield quotes Matisse as saying:

…for me space is one unity from the horizon right to the interior of my workroom…. The wall with the window does not create two different worlds.

This is so different from the way most people see and the way I saw. Matisse shows the unity of what is inside and outside with that vivid and gorgeous blue. And the window, which separates and joins inside and outside, is the exact same width as the table inside, so that, as Elderfield writes, “inside and outside interpenetrate and join in a single blue plane.”

The Outside World & Myself

Growing up in Connecticut, I came to feel it was wisest not to show what I really felt. “Keep it to yourself” was my motto. I was hidden and secretive. I felt I was better than the everyday world around me, including my family, and that my thoughts and feelings were deeper and of a finer quality than those of other people. Meanwhile, I felt lonely, and also afraid. It took what I thought was an act of extreme courage to begin a conversation with someone I hadn’t been “formally” introduced to. When I was sixteen, I was terrified at the idea of going out and looking for a job. This, I learned, was because of the way I had made other people so different from me in my mind—and not only different, but inferior. Matisse’s purpose as he painted was to honor the world different from himself as a means of expressing himself. It is the opposite of the snobbish way I had of seeing the world. I learned from Aesthetic Realism that it was my desire to have contempt, which Eli Siegel described as the “disposition in every person to think we will be for ourselves by making less of the outside world,” which made me want to keep myself separate.

The way I treasured my own thoughts, making myself “special,” was against seeing value and meaning in the outside world—and I am grateful this was understood and beautifully criticized. For instance, in my first Aesthetic Realism consultation I was asked to read Christina Rossetti’s poem “Who Shall Deliver Me?,” which has these lines:

All others are outside myself;

I lock my door and bar them out,

The turmoil, tedium gad-about.

My consultants asked me:

Do you think every thought you had has something of the world in it? That even if you separate yourself, go into a room like Christina Rossetti, your thoughts are going to be about something in the world?

This began my study of how to see that what went on inside of me was the same as the world around me. The relief I felt learning this made me want to skip down the street!

Art Asks This

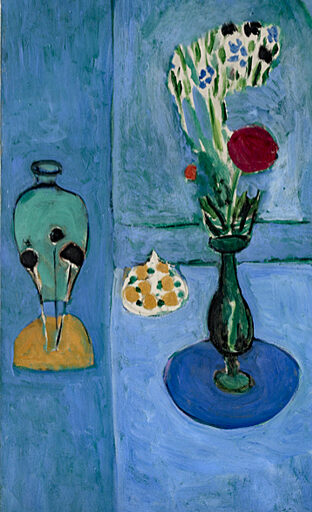

Matisse makes us look and ask “Just what is outside? What is inside? You may be very surprised!” Inside on a table, we see objects placed in front of us thoughtfully and carefully.

From left to right, there’s a green vase, a small, decorated jar with green and gold dots, a vase of flowers, a cast of an antique head, an ocher-colored dish with a blue brooch, what is probably a mirror, Elderfield says, framed in red, and a desk lamp. These objects are clearly inside.

But look at the cast of the antique head. Arising out of the top of its head is that black vertical line which looks like the mullion of the window—the strip of wood or metal that separates the panes of glass. And to the right, arising from the top of the desk lamp, is another vertical black line. Is it the window—inside? Or is it the tree—outside? And if it is part of the window, how can that round, blue shape—the tree—be in front of the window, inside? As we follow the line upward, it curves and branches off. We know it is the tree, but we also feel it is the window.

But look at the cast of the antique head. Arising out of the top of its head is that black vertical line which looks like the mullion of the window—the strip of wood or metal that separates the panes of glass. And to the right, arising from the top of the desk lamp, is another vertical black line. Is it the window—inside? Or is it the tree—outside? And if it is part of the window, how can that round, blue shape—the tree—be in front of the window, inside? As we follow the line upward, it curves and branches off. We know it is the tree, but we also feel it is the window.

And look at the flowers of red and blue and white in the green vase. The large red flower clearly arises from the vase, is inside. But the flowers of dark blue and white: are they inside or outside, a part of Matisse’s garden? Matisse has painted them to show what is inside and what is outside are continuous, can be seen as one.

We Have an Aesthetic Problem

I think this understanding of the self, as described by Eli Siegel in the journal The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known #232 titled “In and Out,” needs to be known and studied by every person in the world:

The problem made for by inner awareness existing in a person along with the unlimited desire to see what is different from oneself, is an aesthetic problem.

Matisse is solving this problem in outline as he paints an interior of a room—which has been seen as a metaphor for the inner self—and shows how continuous it is with what is outside. The artist criticizes our desire to separate “inner awareness” and “the unlimited desire to see what is different from oneself.”

I was affected looking at those objects inside, to see that although they are familiar and recognizable objects, they have such a mystery to them. The antique cast is bold in color and form, and yet the lines and markings of the face make it unclear just who or what this is.

I was affected looking at those objects inside, to see that although they are familiar and recognizable objects, they have such a mystery to them. The antique cast is bold in color and form, and yet the lines and markings of the face make it unclear just who or what this is.

And what Elderfield describes as a “green Chinese vase,” on the left-hand side of the painting, seems to fit in with the rest of the painting. But what is supporting it? The way Matisse has placed it on the same horizontal line as other objects, helps to make it feel secure, and meanwhile it seems to exist in a realm of pure abstraction. It is familiar and strange, secure and free in space. That blue vertical band on the left, which contains the vase, is important to the composition. Without it the drama of inside and outside as different and the same would be diminished.

I was once asked in an Aesthetic Realism consultation: “[Could] you feel the world as getting deeper and wider without being terrified that you’ll be less?” I said I didn’t think so. I preferred what was close to me and familiar. I liked to arrange the objects on top of my dresser—two small china angels, perfume bottles and a jewelry box. I felt if they were neat and in order, somehow I was all right and composed too. I used the way I could manage and arrange objects close to me against the world as deep and wide. Matisse uses the objects in his room to see more the grandeur of how the whole world is made.

The Purpose of Art

A central purpose of all art, I have learned from Aesthetic Realism, is to have what is inside, internal, made one with the external. The purpose of art is to like the world. This painting is a beautiful illustration of that.

A central purpose of all art, I have learned from Aesthetic Realism, is to have what is inside, internal, made one with the external. The purpose of art is to like the world. This painting is a beautiful illustration of that.

In his book, John Elderfield writes of this work: “The whole set of ovals and circles inside and outside the window so clearly share a common order of being that inside and outside are given as one.“

The round shapes of the mat and dish on the table are the same shapes as the bushes and trees outside; the triangle and square shape of the antique cast are related to the yellow diamond shape in the distance; and the oval shape of the blue brooch is the same shape as the cloud floating in the sky.

Matisse’s color, too, relates inside and outside, as that warm, golden color of the cast is so near to the golden diamond, which is the exterior wall of Matisse’s studio outside in the garden and is the brightest point in the painting. The large blue circles outside the window are like the blue mat on the table. And the tabletop, the thing that is nearest to us, inside, has almost the same pale blue color, painted with the same brush strokes as the sky, outside.

The way Matisse has painted those objects on the table, they seem to be saying “Look at me! Don’t look past me!” At the same time what is distant, what is outside looks friendly, too—the large curves of the bushes are soft, while they still have a vivid blue color. And Matisse’s studio looks snug, nestled between two hills. Or is it two bushes that are closer to the window? Matisse doesn’t play off what is inside against what is outside as I once did. He critically and lovingly keeps our thoughts in motion, insisting we be fair to both.

Because of the way Matisse relates inside and outside, the outside world is made warmer and at the same time the inside objects are more meaningful and take on grandeur. They are not made less mysterious or less special as I was once afraid I would be through being seen in relation to a deep, wide world; they are more wonderful!

Because of the way Matisse relates inside and outside, the outside world is made warmer and at the same time the inside objects are more meaningful and take on grandeur. They are not made less mysterious or less special as I was once afraid I would be through being seen in relation to a deep, wide world; they are more wonderful!

Through the study of Aesthetic Realism the opposites of inside and outside—what I feel to myself and what I show—came to be in a happier, more integrated relation. I truly became a person in the whole world, which includes my marriage to Dan McClung, our daughter and son-in-law, and a career as a New York City public school teacher of over 30 years. Now I want to see truly what the world is—not make up a better world in my mind. I am grateful to have learned how to see myself and what is not myself—the world—in an aesthetic relation. Through this magnificent education, this is possible for everyone.

From the historic Terrain Gallery series—”Aesthetic Realism Shows How Art Answers the Questions of Your Life!” Barbara Spetly McClung taught in New York Public schools for many years. She and her husband Dan McClung are Aesthetic Realism Associates and have presented talks in this series. And with sociologist and Aesthetic Realism consultant Devorah Tarrow, she’s conducted workshops at schools & conferences on “Harriet Tubman, the Underground Railroad, the Cause of Slavery, & Us!”