By Dorothy Koppelman

A form of this article appeared in the ASCA newsletter Fall 2003 [American Society of Contemporary Artists].

Surely, this monumental sculpture of a man with his feet on the earth as he rises over seven feet exemplifies that oneness of opposites which Eli Siegel, founder of the philosophy Aesthetic Realism, described as central in life and art. This is Mr. Siegel’s question in his immortal Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? on “Heaviness and Lightness”:

Is there in all art, and quite clearly in sculpture, the presence of what makes for lightness, release, gaiety?—and is there the presence, too, of what makes for stability, solidity, seriousness?—is the state of mind making for art both heavier and lighter than that which is customary?

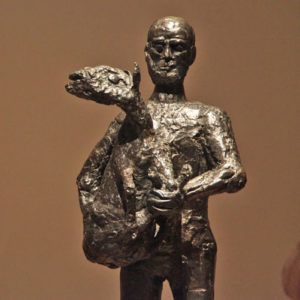

Looking at Picasso’s Man with a Lamb in 1945, shortly after the figure arrived in New York, I was so struck by the impact of this man, roughly hewn, heavy, mute, coming towards us over many centuries—this tall, massive figure gripping the legs of and simultaneously cradling the young lamb with his thin, yearning, outstretched neck—I simply dissolved in tears. The artist has given us man, at the beginning both raw and noble, a brute with immense kindness—at once solidly on the earth and rising proudly in space.

Early in my study of Aesthetic Realism, Mr. Siegel explained to me that I wanted to feel I was the same person when I was lighthearted as when, as I told him, I could just sink and feel hopelessly heavy. He saw too that I wanted, through my work, to resolve that conflict—to see how something heavy could become light. Mr. Siegel taught that the way of seeing we want in our lives is to be found in art, and this is what I experienced. He explained: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Studying this principle, I felt a new coherence for myself of heaviness and lightness.

Picasso did this work during the last year of World War II and his preparatory drawings are described by Roland Penrose: “In March 30, 1943, the shepherd is the loving father who clasps a confident lamb to his bosom.” However, the bronze as Picasso finally built it has a mingling of utter sweetness, lightness, on one side, and then, on the other, that form of heaviness which is a sullen cruelty. These opposites are made one in the swift, firm, and rough construction of that face with its jutting lip, which is both intense and also delicately formed; there is tenderness.

That lamb, gripped on one side, cradled on the other, emerges from the center of the man—and gripping and cradling are aspects of heavy and light. The man’s elbow on the right is like the lamb’s leg on the left. One leg is held by the clumsy fingers; the other, catching the light, is free. The animal is simultaneously held close and lifted into the air: stability and lightness are one. Picasso uses the same rough texture, the same method of small patches and scraped surfaces, to build the bodies of the lamb and the man; together their heads—one so high and round, the other stretched forth—go up, down, and out. We are satisfied that they belong together.

I can think of nothing more beautiful than the knowledge Aesthetic Realism provides of how to put opposites together in ourselves, and to see them as one in art.