By Barbara Buehler

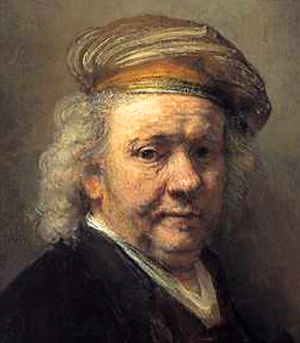

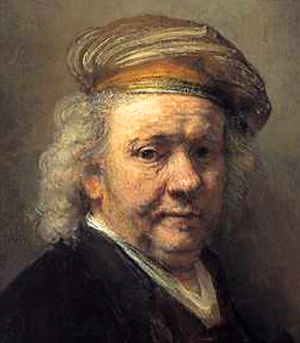

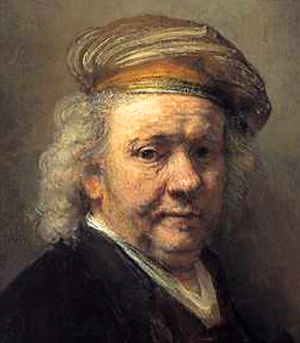

I have loved this painting from the time I first saw it in 1971 at the Mauritshuis, The Hague. It is the last of about sixty self-portraits in oil Rembrandt van Rijn did, and is dated 1669, the year he died, at age 63. I bought a postcard reproduction of it then and brought it back to New York City. Often, coming home to my apartment after work, I would look at it. I loved its warm, golden light. And though there is sadness in his face, I felt Rembrandt looked out with warmth and kindness. This was so different from the coldness I worried about in myself.

I often had a hard time looking directly at someone. I thought of it as shyness. But the truth is, I was not proud of how I saw people, thinking I was too good for most of humanity. I felt, as I have learned many people do, both superior and inferior, and I didn’t see there was any relation between the two. Then I came to see, through my study of Aesthetic Realism, that Rembrandt’s painting, in its technique, answered one of the largest questions of my life. “All beauty,” Eli Siegel writes, “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” In this painting, as he looks at himself, Rembrandt is both modest and proud, and we feel his humility is the same as his grandeur.

I. How Should We Look at Ourselves?

For the last 20 years of his life, Rembrandt was worried by debts; he’d had great renown and prosperity, but in his later years he lived in comparative obscurity. At the time he painted this self-portrait in 1669, he was ill. Yet in the midst of this, he was courageous.

In the important book, Rembrandt: Life and Work, Jakob Rosenberg writes:

“Why did Rembrandt show such an untiring interest in his own features?…Rembrandt seems to have felt that he had to know himself if he wished to penetrate the problem of man’s inner life….In this constant and penetrating exploration of his own self, his range went far beyond an egotistic perspective to one of universal significance.”

As I read this, I saw something about the difference between the way of seeing Rembrandt as artist had that has made people love him, and the way of seeing I had as I looked at myself: I was wonderful one minute, and a wretch the next. Most people don’t think about themselves, “I represent humanity, with its strengths and weaknesses, confidence and uncertainty, hope and sorrow.” But it is Rembrandt’s seeing of these opposites as simultaneously present in his own face that makes for the “universal significance” Rosenberg describes.

II. Pride and Humility—The Whole World Is in a Person

In this painting, Rembrandt places himself squarely in the center of the canvas. He looks out at us, with no other objects or landscape beyond. This is very assertive. Yet there is a delicate mingling of himself and space. In fact, he seems to come from space and merge with it. Rembrandt takes some of the color from the background and blends it into his coat, blurring the edge so that it is hard to see where he ends and space begins. Jakob Rosenberg describes the effect:

“Outlines are broken; they are only partly visible, partly obscured. Space takes on a less geometric character, with less tangible limitations, but suggesting an imperceptible transition from the finite to the infinite. Along with light and dark, colour too gains a new symbolical significance, and a vibrating atmosphere pervades the whole picture, heightening the interdependence of all parts and preventing forms and surfaces from becoming isolated or over-distinct.”

Yes, Rembrandt’s features seem to come out boldly on one side with that bright, golden color, and there is a hint of a smile. The other half of his face is darker, receding, with an expression that is puzzled—even troubled. Rembrandt is showing two aspects of himself, standing for humility and pride.

We can see this on the left side of the canvas, how in the midst of that golden brightness, there is darkness too—in the shadows around his mouth and eyes, beneath his ear, within his hair, and most movingly, in that deep line that etches his face, starting from the inside corner of his eye and circling beneath it, looking like a fissure in the earth. And on the right side of the painting, see how, in the midst of that darksome face, there are glimmers of light? And there is the slightest bit of white sparkling in his dark eyes.

III. There Are Light and Dark, Too

In an essay Eli Siegel explained:

“A technical way Rembrandt had of liking the world was to make a one of light and shadow. Rembrandt is noted all over the world for this. Furthermore, Rembrandt was busy showing deeply that a grieving thoughtfulness was at one with human radiance.”

Light and dark, “a grieving thoughtfulness” and “human radiance,” are inextricably mingled too in the rich dark of the coat or drape hung across Rembrandt’s shoulders, and the bright angle of his V-shaped collar.

I love the energetic way the hat he is wearing is painted. Technically, it is a oneness of humility and pride, so different from the way a person can strut one moment and then be meek and humble the next. Look how the hat swells up and out above his forehead at the left, and then curves around his head and falls at the right side. Rembrandt’s brush strokes of bright gold are bold. A magnificent light illuminates the front of the band at the bottom of the hat, yet notice too how the band, like his face below, blends into the shadows as it sweeps to the right.

This hat is a criticism of how, in my everyday life, I could want to see things as very sad, even drooping, and not want to see them as having brightness or radiance. In an Aesthetic Realism lesson I had the honor to have with Eli Siegel, he asked me:

Eli Siegel: You are particularly taken by sunsets?

Barbara Buehler: Yes.

Eli Siegel: And you prefer the world as it’s fading rather than the world as expanding? And the world as somnolent and a world as dim is also what you prefer?

Barbara Buehler: Yes, it is.

Seeing that I actually preferred to see the world as somnolent and dim as a means of making myself superior and glowing, changed me deeply! For instance, I saw that I preferred my own dreamy thoughts to listening to what other people said, which I made dull and unimportant. This, I learned, was contempt, and against my deepest desire—to like the world. I am deeply grateful to Mr. Siegel for understanding me truly and teaching me how to know myself.

See how Rembrandt’s hat puts together the “fading and expanding” that are one in a sunset. Look at the band of red on the hat. It is one of the boldest colors in the painting. It expands and then blends and disappears into the shadows. It asserts itself, and at the edges yields to and merges with what surrounds it. Does Rembrandt use this hat to both criticize and encourage himself? The hat has pride, a kind of nobility—and a verve. It seems to say “Don’t give up. There is more to see!”

One of the areas of the painting I think is most beautiful is the golden light on Rembrandt’s forehead. There is something so proud in its bright assertion. This, I learned, is achieved technically by the building up of layer upon layer of paint in this area of the canvas. And this place, which reflects light so brilliantly, stands for Rembrandt’s mind, the place of his deep thought. The light is so intense it seems to come from within as much as it shines from somewhere outside the canvas. Rembrandt as artist shows that really wanting to know oneself puts together humility and pride.

It moves me that the comprehension Rembrandt looked for all his life, and with such poignant intensity in this, his last self-portrait, is in the knowledge of Aesthetic Realism. That is what I met and what people everywhere are looking for.

Barbara Buehler, Associate City Planner with the New York City Department of Planning (retired), and Aesthetic Realism Associate, studied in classes with Eli Siegel, and studies now with the Aesthetic Realism Chair of Education, Ellen Reiss. She has given groundbreaking presentations with architects Anthony Romeo, Dale Laurin, and filmmaker Ken Kimmelman.