By Dorothy Koppelman

I am going to talk about what I have learned in these years which has had such a tremendous effect on my life, my work and myself. I will talk too of the 17th-century Spanish painter, Diego Velazquez, whose study of objects and great paintings of the Spanish court put together opposites which trouble us every day, and without which, I know, there would be no art: pride and humility.

From the time I can remember I had two contradictory ways of being. I felt happy when I was drawing and proud learning how to paint; I also felt superior to all the people I knew and finally left home to get away from. I would spend hours trying to draw a bowl with the right perspective, or copying a figure to see if I could get it to look three-dimensional—and then go out with my friends and make fun of all the bourgeois people of my native Brooklyn. I could go from feeling exuberant to miserable in the course of an hour.

Mr. Siegel asked me in my first Aesthetic Realism lesson: “Do you like the way you see the world?” Just being asked that question made me think differently. I had no idea there was any such thing as an attitude to the world which governed me, and colored everything I saw or did. I learned that contempt, my quick scorn which I thought I had a right to, and which I thought made me so distinguished and gave me such a lift, is what made me later want to sink into the ground.

In one lesson Mr. Siegel told me: “Ask yourself: are you going to build yourself up by lessening other things, or by seeing meaning in them as far as it takes you? You will like yourself and feel proud if you are trying to give justice—full value—to all things.” Mr. Siegel showed me I was the same as and different from every thing, object, person. He asked me: “Are you unique?—Are you related to everything? Are these opposites? Are the opposites you?”

As I came to feel that I did not want to manipulate things, deviously manage situations or distort people contemptuously in my mind, I felt freer—I could hold my head up honestly; my angry outbursts simply stopped, and so did my desire to fade into the wallpaper. Aesthetic Realism taught me the two things every person needs to know; what I most disliked about myself and what the beauty of the world really is. I am a happy person because I heard the aesthetic criticism of self which distinguishes vanity from pride, and which frees a person from the shackles of contempt.

I. “Successful Humility Is Pride”

I first came to really care for and increasingly understand the paintings of Velázquez studying Mr. Siegel’s incomparable essays in art criticism. In “Art As, Yes, Humility”, Mr. Siegel writes:

In artistic seeing, humility and submission are pride and grandeur….Successful humility is pride.

I saw in this work, The Surrender of Breda, the beauty of submission and pride at once.

This is one of the few historical paintings the artist ever did and I believe he painted it because he was so moved by the drama of opposites in a battle situation, and the story of gallantry at the time of surrender.

Right in the center of the painting opposites are one as the two generals meet. One, in his dark armor, gallantly reaches over to touch the yielding, bowing general who so sweetly holds out the key to the city. The motion of the rising and falling rope echoes the motion of the heads, one high, the other low. But between those heads marches a row of white spears, joining them. In the center, an upright and softly furled flag, proud and humble, signals peace. I was so moved by these two men, taking their hats off to one another, that I wanted to be like them, yielding and victorious.

When Mr. Siegel looked at a reproduction of this central detail, he wrote a comment: “destined consent.” I think that is what a person feels when he can say, Yes, and proudly surrender to the beautiful structure of opposites in reality and in himself.

Diego Velázquez was born in Seville in 1599. As a boy he was apprenticed to painters, the second of whom, Juan Pacheco, wrote The Art of Painting in which he tells how, from the age of 11 to 19, Velázquez studied ordinary objects and paid a peasant boy to pose for him so he could study facial expressions. What the artist wants to do is what every person wants to do and Aesthetic Realism teaches how. In “Art As, Yes, Humility” Mr. Siegel writes:

To see is to be humble….To be pleased by an object, by what it is, its form, texture, color, relation, is felicitous, sometimes magnificent, humility. It is a humility one has to learn.

Diego Velázquez painted this Old Woman Cooking Eggs when he was just 19. The critic Raymond Cogniat writes that the artist approached—

portraits of peasants with as much respect as those of great noblemen, and a simple still-life with as much exactness and care as a composition on a grand scale.

The lesson of art is here: every familiar face and situation including our own living rooms can be seen with new respect, with wonder.

Velázquez has looked at the perfection of that oval egg, held over that light, circular dish, itself crossed by a dark knife, and has seen the great meaning of opposites—an eternal moment of “unbounded significance.” Light and dark, hard and soft, sharp outlines and obscured forms are composed.

A young person, somewhat modest, holds a heavy melon as he faces an older person. Placing youth somewhat further back, gives one a sense of age, while age itself, brilliantly lit, becomes vividly in the present. The luminous, whole egg and the softly spreading eggs being cooked, the heavy round melon on the left, and the round dish on the right makes our eyes move back and forth, even though the stirring motion of the wooden spoon in the old woman’s hand is caught and made—in its sculptural quality—timeless.

I think about Velazquez when I am cooking eggs sometime in the morning, and every time, stirring them, I feel wider, my feelings lighter. I am related to the woman of 500 years ago.

I love teaching with my colleagues in Aesthetic Realism consultations, the technique of art: the first assignment is: Every day write a complete sentence about one thing in the outside world you like. That is the beginning point in liking the world that thing and you come from.

And if a person is feeling low, we ask is it because he or she has made less of the outside world? We ask a person to look at an object close to you: Are you like the chair you are sitting on, feet on the floor, back upright; are you at rest and alert? This way of seeing the world combats conceit. Eli Siegel taught that because the opposites of reality are in us, “when you lessen the meaning of anything you lessen yourself.”

In consultations people study how to see other people and objects with the meaning they have. Recently a New Jersey woman told us in a consultation how efficiently she managed her home, her part-time job, her garden; she whipped things into shape on a whirlwind schedule. She felt noble and martyred, but she did not like herself and she did not sound proud.

When we asked if her husband had any criticism of her, she smiled and said, “He says I act superior. I don’t sit down and talk with him. I’m always jumping up to do something.” We suggested that she look at and study an object in the store where her husband worked and which he cared for. For her next consultation she wrote:

My husband and I are having a wonderful time talking about hardware, a pliers, the head of a nail…and I see the opposites in them—hardness and softness, sharpness and roundness!

She wrote exuberantly that objects she had taken for granted were so “simple and complex like me, like Harry and everything else that exists!” She was in the midst of seeing what Mr. Siegel said: “Successful humility is pride.”

When Diego Velázquez was not yet 23 his paintings had already attracted attention in his native Seville, and he went to Madrid where his work might be seen more widely. By the time he was 24 he had become, as the Metropolitan Museum’s brochure of the exhibition of the artist’s work puts it, painter to the king, who took a personal liking to him and monopolized the artist’s work for the rest of his life. Henceforth most of his paintings were portraits of the royal family or members of the court.

Velázquez is great because he had the same purpose as he looked at a king, a princess, and later at buffoons and dwarfs, as he did looking at the peasant boy, an egg, the humble objects of a kitchen.

In the “Free Poem on ‘The Siegel Theory of Opposites’ in Relation to Aesthetics” in his book Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana: Poems, Eli Siegel puts into proud music, the painter’s vision and his work. These are some lines:

Velázquez’ characters resemble those

Of Shakespeare—stern and delicate; alive:

And so, at times, grotesque. The vision of

What’s here meets vision of what’s far away—

A thing reflected mingles with the here,

The seen. When Hamlet is made one with space,

It is like doings in Velázquez’ work…

2. A Person Is High and Low: Aesthetic Opposites, Ethical Opposites

I have learned from Aesthetic Realism that a painting solves in outline the questions of our lives, including of the person doing the painting. When we see height and lowness made one in a painting, when we look up and down for the same purpose, humility and pride are closer in us too. Every artist is dealing with these opposites in himself as he paints.

In the Spanish court Velázquez felt he was both “ennobled” and in “bondage” as the Metropolitan Museum catalogue puts it. He had the high esteem and affection of the king but in order to have economic security for himself and his family he had to be employed as “Gentleman of the Bedchamber.” He arranged for the construction of buildings, he hired the carpenters; he served as the king’s ambassador all over Italy choosing and buying works of art for the Palace. Meanwhile in 17th century Spain being an artist was a “low and base calling.” On the one hand, he was the king’s preferred painter—and famous—on the other hand he was given duties “onerous, burdensome, time-consuming.”

Velázquez felt justly that his true pride came from his way of seeing, and he wanted the profession of painting to be lifted from its low status. At the same time, he was intent on being admitted to an order of Knighthood, and spent many years trying to obtain documents proving that his Portuguese father was of noble birth with no taint of “impure blood.”

It is likely that his tiredness as time went on came from an unseen conflict in him about where his vanity might take him and where his true pride was.

One of the greatest triumphs of art—and it was the triumph of Velázquez—is the finding of beauty in the ill-formed, the misshapen, the ugly. In 17th century Spain, dwarfs were seen as low and pitied, and sometimes were taken care of, and served as jesters to lighten the burdens of the monarchs. Velázquez, however, looked at the dwarfs for a different purpose; he saw the opposites of reality. He has had a good effect—he has made for true humility in the hearts and minds of every person seeing this beautiful painting.

Here is Sebastián de Morra. We see a broad, light brow and eyes that in their depth make one almost cry with love. See how the arms, with their light and sturdy fists press down?—the little legs come towards us and the light slippered feet point upwards with their tops glowing softly? Those feet, with their curved motion, and vertical direction make us feel a standing person. The kindness of art is that we cannot look down on Sebastián de Morra without looking up.

The dwarf is in the center of the canvas. His dark green coat is divided up and down the middle, and just where his fists press down there is another division right across the center. We find perfect geometry in that imperfect body. Let your eyes travel around the shape of the whole man. It’s a circle, the most complete, continuous, non-stunted shape in the world. Coming out of that circle is the warmth of the whole self of Sebastian de Morra in his light pink and gold cape, with his ever so slightly tilted, questioning head, his wise mouth and those deep brown eyes. This is man as noble.

The purpose of Aesthetic Realism consultations is to teach persons how to see the relation of opposites—the dark and light, the complete and incomplete, high and low, good and evil, in the world and in ourselves. Every painting by Velázquez celebrates that purpose.

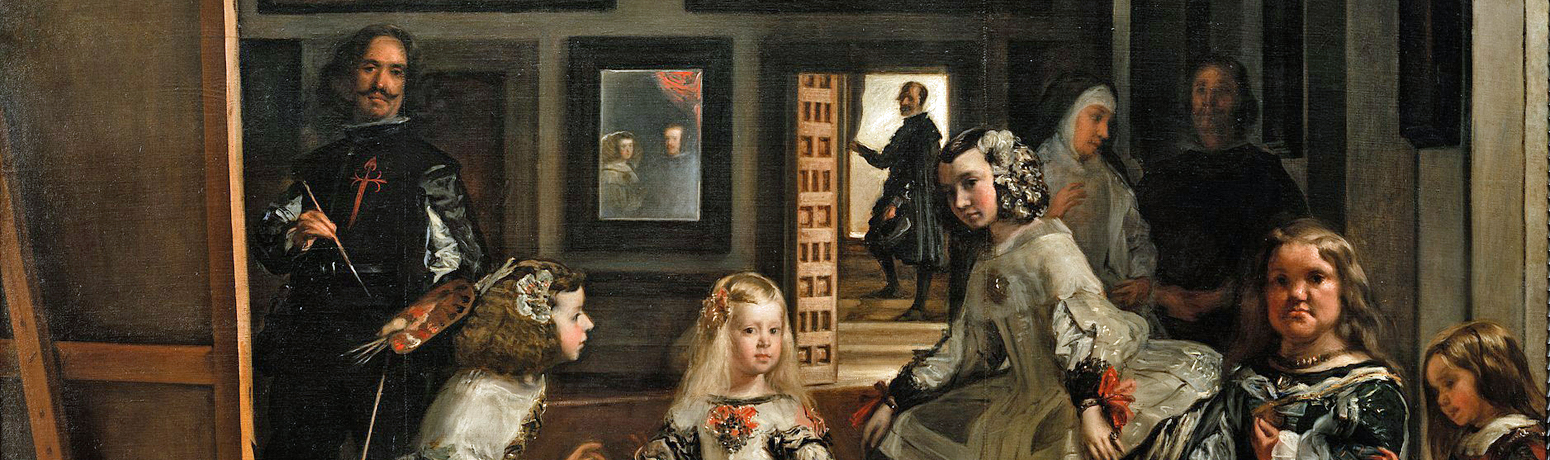

In 1656, four years before he died, Velázquez painted the work—to quote Eli Siegel’s poem—in which, “A thing reflected mingles with the here, / The seen.”

The heiress to the throne of Spain is the center of The Maids of Honor [Las Meninas], but the artist is studying persons high and low as they bow, entreat, kneel and stand by. The large face of the dwarf on the right is so near the imperious little princess. The symmetry of space and rectangle in that dark room has a serene nobility that includes the bumping irregularities of the nobles and servants in the foreground. Velázquez has put together the opposites of all time in the great space of that room; the light that enters as the courtier lifts the curtain becomes warm as it touches the artist’s canvas.

And there is Velázquez himself, looking at the royal couple perhaps, reflected in the distant mirror, and he is looking at us.

Velázquez and his paintings say Yes over the centuries to the most beautiful message in the world: that of Aesthetic Realism, true about the world, true about art, true about every self—it is in these lines of Eli Siegel’s “Free Poem on ‘The Siegel Theory of Opposites’ in Relation to Aesthetics” with which I end my paper:

The opposites are surely elsewhere, too,

In more, more ways, my friends, in more, more things.

Ah, let us see them where they are—because

They make OURSELVES, they make the WORLD, that which

In honesty, we like; in pride, we are.