By Donita Ellison

I have cared for the work of the renowned 19th century French sculptor Auguste Rodin since I first saw an image of his famous statue The Thinker in high school.

As I studied art at Missouri State University and later at the School of Visual Arts in New York, I learned that Rodin has been called the father of modern sculpture. Critic Georg Simmel wrote that he “brought to the human figure an extraordinary variety of movement…[that] reveals man’s inner life, [and] feelings,…thoughts, and…personal vicissitudes.”

He studied the model in motion, and was the first sculptor to present the human body as simply walking.

He took sculpture off the pedestal, placing his figures on the ground. The way his surfaces were expressively rough enabled light and shadow to be an important element in sculpture in a new way.

When I began to study Aesthetic Realism I was amazed to learn that art, including the art of sculpture which I loved, has something large to teach us about ourselves, particularly about the relation of power and kindness in our lives. Every person has the question of how to make sense of ourselves as strong, powerful, and also considerate, kind. These opposites are dealt with beautifully in the work of Rodin in a way that makes for a large emotion of respect for reality, and can give us hope about our own individual confusions.

1. My Mix-up about Power and Kindness

I grew up in Springfield, Missouri and like many women, I once felt that the way I wanted to be kind and also have power were as different as oil and water. There were times I’d want to do good things for people, and even thought about being a missionary or joining the Peace Corps. Yet at other times, I’d imagine myself getting a tough guy on a Harley Davidson motorcycle to melt in my arms. I felt kind when a stray dog came to our home and I gave it food and a place to sleep. But I also liked getting my own dog Trixie to cower in front of me, and then I felt cruel and ashamed.

As a girl I liked music and spent hours listening to records. On Saturday nights my grandfather and I watched gospel quartets on television. I thought it was beautiful how the distinct voices of four men—from the low bass to the high tenor—blended together. But I also was competitive. In seventh grade chorus I compared my own voice to other students’, thinking “Jane’s better than me, but I’m better than Cindy.”

I didn’t think that being kind made me important. Having a big effect on people while feeling superior and unaffected was a fast thrill which I went after more and more. At age 12, when my Grandmother Ellison gave me her credit cards, I felt powerful, telling the saleslady to “charge it.” I bragged to friends that my family owned their own business, a nursing home. Yet in my mind the important thing wasn’t the care of the elderly residents or the working conditions of employees, but the fact that a portrait of me at age ten, in a floor-length yellow chiffon dress hung in the entryway for all to admire.

In an introduction that Eli Siegel wrote in 1973 for an Aesthetic Realism seminar on the subject of power, he explained: “Every person is troubled by the drive towards good power and by the simultaneous drive towards bad power.” Good power, he showed, is “anything that makes you and the world more beautiful.” All bad power, “comes from an insufficient love for what is not oneself.”

This insufficient love for what was not myself, I was to learn, was the reason why, as a young woman, my relations with men did not fare well. My purpose was very different from the purpose of art—which, Aesthetic Realism explains, is to show, through form, an imaginative love for what is not oneself.

2. He Brought Something New to the Seeing of a Person

For many years, it has been felt that the sculpture of Auguste Rodin adds to the beauty of the world—and I believe a large reason is the relation in his work of power and kindness.

All of Rodin’s works deal with what Mr. Siegel called in a lecture “reality in its richest form”: people. His figures convey the power of the human body and the intensity of human feeling, and I believe his work is a means for us to see that the power of art stands for the kindness each of us wants and needs in our lives.

Kindness, explained Mr. Siegel, “represents the beautiful, accurate way of seeing things.” That is the power Rodin has mightily given form to in bronze, in his monumental work The Burghers of Calais. This work was commissioned by the town of Calais to honor a heroic act that took place in 1347 during the 100 years war, when the King of England agreed to spare Calais if six of its foremost and wealthiest citizens sacrificed their lives. Though eventually, the lives of these six men were spared, Rodin chose to present them walking to their execution, clothed in long shirts with nooses about their necks.

This work was commissioned by the town of Calais to honor a heroic act that took place in 1347 during the 100 years war, when the King of England agreed to spare Calais if six of its foremost and wealthiest citizens sacrificed their lives. Though eventually, the lives of these six men were spared, Rodin chose to present them walking to their execution, clothed in long shirts with nooses about their necks.

Rodin’s technique in sculpting these figures—who seem powerless—makes for an effect of great power. The work is kind, for it makes us get within the feelings of these men as they walk to their supposed doom.

Rodin honors the individuality of each man, modeling with subtlety and precision the particular and ever-so-personal thoughts and emotions, which show in their expressions and gestures. In ordinary life, we often rob people of their individuality, lumping them together in our mind, or focusing narrowly on a person without wanting to see his or her depths or relations. Rodin honors the relation among these men and gets within the uniqueness of each.

Mr. Siegel wrote in the comment to his definition of kindness, “To be kind we must have the imagination arising from the knowledge of feelings had by others.” And we feel this kind imagination through the dramatic angles of arms and legs and the heavy curves of heads and shoulders.

There are both resignation and strength in how their long shirts hang in loose folds and also have sharp, upright creases. There are determination and reluctance in how their bodies move forward and hold back. And all of this modeled in clay and cast in bronze! The kindness of this work encourages us to want know and be deeply affected by the feelings of these men.

In the figure of Jean d’Aire, Rodin shows this man’s restraint in his rigid stance, his pursed lips, and clenched fists, and also his profound worry in the soft modeling of his furrowed brow. (click on thumbnails to see larger image)

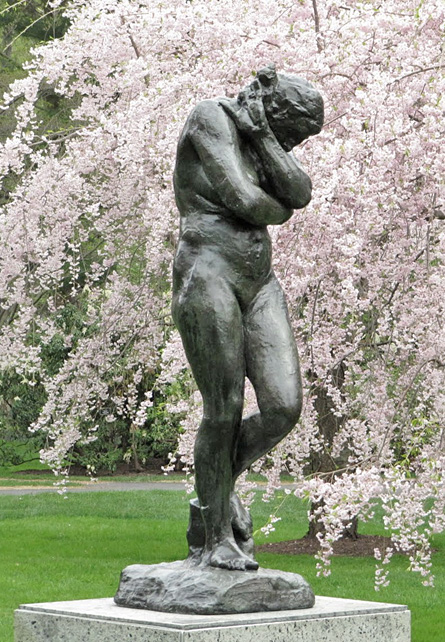

There are grace and humility in the heavy bowed head of Eustache de Saint-Pierre, his eye downcast, looking at the ground before him with resignation and resolve.

In Pierre de Wiessant there are yielding and anguish, grace and tension in the bend of his head and upward thrust of his hand and fingers.

We see for and against in the figure of Andrieu d’Andres. Overcome by grief and agony, he covers his head with his hands, as the right angle of his foot impels him forward.

We see for and against in the figure of Andrieu d’Andres. Overcome by grief and agony, he covers his head with his hands, as the right angle of his foot impels him forward.

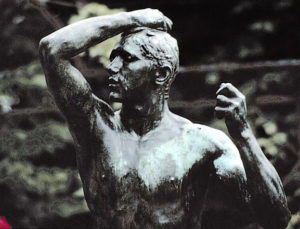

In Jacques de Wiessant reluctance and defiance are present as his step seems to hesitate and his elbow sharply thrusts outward.

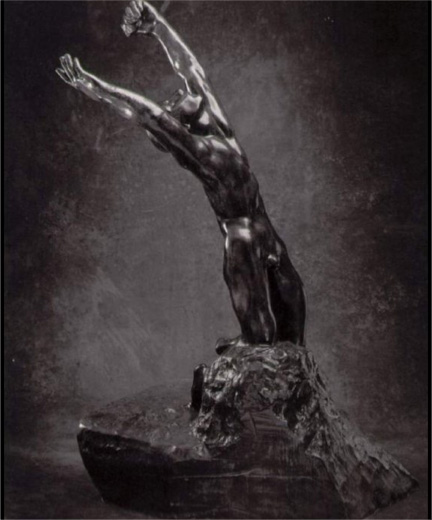

And, in Jean de Fiennes with his open arms we see willingness and disbelief; Rodin conveys his deep uncertainty through the differing directions of his head, arms, torso, feet.

And, in Jean de Fiennes with his open arms we see willingness and disbelief; Rodin conveys his deep uncertainty through the differing directions of his head, arms, torso, feet.

Kindness, said Mr. Siegel “is accuracy,” “the height of subtlety… [and] perception…” The power of Rodin as artist is impelled by that subtlety and perception.

The artist, writing of his own work, said that he wanted to:

express each swelling [of the surface as] the efflorescence of a muscle or a bone which may lay deep beneath… And so the truth of my figures, instead of being merely on the surface, seems to blossom from within to the outside, like life itself.

3. What Can a Woman Learn from Art about Love?

In an Aesthetic Realism lesson Mr. Siegel described the feeling a woman can have in going after power over a man: “The more he needs me, the less I’ll need him.” And he said: “The more men are moved by you, the less you want to be moved by them.”

This was true of me. I practiced how to have the most imploring look, how to toss my hair in a nonchalant way, and I would arrange to be in the right place at the right time for the right man to just “happen” to see me. But I didn’t see the young man I was pursuing as having hopes and feelings as deep as my own. I wanted him to fall for me while I remained hidden and intact. I was after power, and it wasn’t kind.

In telephone consultations from Springfield, I learned that the reason love had failed, the reason I didn’t like myself, was that I wasn’t true to my deepest purpose—to be fair to the world and people. Instead, I was after having power based on contempt, and for this I deeply despised myself. In an early consultation I spoke about a man whose attentions I was desperate to get. I said, “I would like to just deal with a man on a level that’s not this game business, you know.”

My consultants asked: “What in you stops you from being able to talk to a man in a way that you’re proud of? People either flirt or they’re honest. Which do you do?

Donita Ellison. Well, sometimes both.

Consultants. Do you think there’s a kind of cruelty in flirting: you show a man that you’ve affected him and he hasn’t affected you? Do you think a person who flirts is interested in power?

I was! And referring to my care for the art of sculpture, they asked: “What is the difference between the way you see men and they way you see sculpture? Does a sculptor flirt with stone or wood?” I began to learn that the power of art is always kind because its purpose is to be fair to an object, to see it with respect and form. And I began to be educated about what kindness truly is when my consultants asked me to read this, from the comment to Eli Siegel’s definition of kindness: “A person is kind who feels a sense of likeness to other things; who accepts accurately his relation to other things.”

For me to see my relation to things, and very much to men, I was given an assignment to write: “Do I See Men Accurately?” I began to see what a man most hopes for is like what I, or any woman, hopes for—to have a purpose with the world and people that we can like ourselves for. And, for the first time I felt it was possible for me to be deeply affected by a man and to be kind—to have a good effect on his life. This is what I am experiencing in my happy marriage to Dr. Jaime Torres. Jaime strengthens my life through his deep and surprising humor, and his criticism, which I’m happy to need in order to be the person I hope to be.

4. The Artist Has Power through Being Affected

The purpose of an artist, I learned, is very different from the purpose I went after in love. The artist does not “flirt” coldly with his material. He wants to be affected deeply by it, and this shows in his technique. Auguste Rodin studied and was greatly moved by the power of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, and by the great Michelangelo. It was Michelangelo who, Rodin said, “held out his powerful hand,” “and revealed to me the truth of forms.” Power, explained Eli Siegel, “is the ability to be affected by true power.” Rodin, as artist, had that power and a grand result of it, is his Monument to Balzac.

In 1891, when the artist was commissioned to create this monument, Balzac had been dead for over forty years. Rodin wanted to know everything he could about Balzac for the purpose of creating a sculpture true to the grandeur of this French writer who had been described as a “force of nature.”

In 1891, when the artist was commissioned to create this monument, Balzac had been dead for over forty years. Rodin wanted to know everything he could about Balzac for the purpose of creating a sculpture true to the grandeur of this French writer who had been described as a “force of nature.”

Rodin read everything by and about the author. He looked at portraits of Balzac, meticulously creating studies of each in clay and plaster. To understand the physical stature of the man, he had a suit of clothes made from measurements had by Balzac’s tailor, and sought out models of a similar build. Rodin’s studies show his figure clothed and nude, feet together and apart, head to the side and back, arms in front and behind—and all this to express, he said, Balzac’s “intense labor,” “his incessant battles,” “his great courage.”

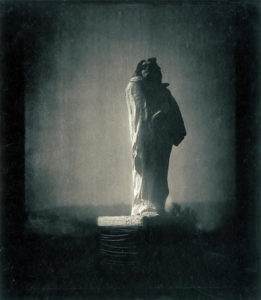

In this photograph taken by Edward Steichen, we see Rodin’s Balzac rise up from the earth, and with a towering height of 10 feet and massive girth, he appears to be a geological force. He seems to step forth, lean back and pause, seeming to take in and be affected by all space. We see a figure putting himself forth powerfully, yet considerate of what is around him. Rodin himself said:

My Balzac, by its pose and look, makes one imagine the milieu in which he walked, lived, and thought. He is inseparable from his surroundings. He is like a veritable living being.

There are both weight and energy in the upward diagonal tilt of the head. And look at how that broad curve created by the gathered edge of the robe sweeps about him like a great wind, as the collar flips up in three briskly spirited points framing his rough-hewn face.

There are both weight and energy in the upward diagonal tilt of the head. And look at how that broad curve created by the gathered edge of the robe sweeps about him like a great wind, as the collar flips up in three briskly spirited points framing his rough-hewn face.

Much has been written about Balzac’s robe and when this work was exhibited in 1898 it was mocked by the critics as “appalling,” a “snowman,” “a side of beef,” “Balzac in a hospital gown.” But Rodin’s research had been careful. He knew that it was the writer’s custom to wear a monk’s robe while writing. In defense of his sculpture, Rodin said:

If truth is imperishable, I predict that my statue will make its own way….This work that men ridicule…is the result of my whole life.

Now over a century later, this statue, a oneness of power and deep, kind perception, has made its own way. And what it, and art as such, can teach us about ourselves, people everywhere in America need desperately to understand. For this to be, Aesthetic Realism needs to be known, because it shows, in a way new in the world, the relation of the technique of art and the questions of our very lives.

Donita Ellison, originally of Springfield, Missouri, is a printmaker and sculptor who taught fine art for 18 years at LaGuardia High School for Music & Art and the Performing Arts, and is an Associate at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, both in New York City.