By Miriam Mondlin

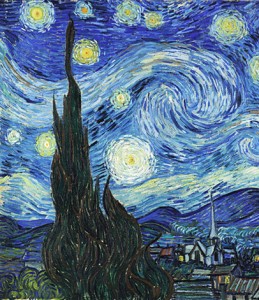

I first saw Van Gogh’s Starry Night at the Museum of Modern Art, when I was about 8 or 9 years old, and I kept going back to look at it again and again. I loved the intensity of the sky, with its tremendous energy and bright, swirling stars, yet the valley below with its snug houses seemed so peaceful. I thought it was beautiful.

Ten years later, I met the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel, and I learned the reason I loved this painting, and why it has stirred people for more than 100 years: what makes this painting beautiful is the way it puts opposites together, and these are the same opposites we are trying to put together in our lives. I am grateful to be studying this principle, Eli Siegel’s statement:

All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.

Technically, beautifully, this painting answers the central question of my life. When I was a child, though I liked going to museums and to the big movie palaces of the 1940’s with stage shows that burst with energy and excitement, like many people, I was essentially disdaining of things, preferring to stay close to home. I learned from Aesthetic Realism that one of the results of my wanting to have contempt for the world, to see it as unfriendly and not worth getting too excited about was that I punished myself by having inordinate fears.

I will speak about how the opposites of expansive and contained are made one in this great painting. The composition has many energetic brush strokes in a circular motion bursting forth in the dark sky. There is a feeling of expansiveness. At the same time, the black outlines of the cypress, mountains, houses and trees gives them containment. The downward blue and black brushstrokes of the mountain slopes are both contained and flowing, and there is a moonlight glow which makes for expansiveness.

The round forms of the trees curving down, make for a feeling of containment, yet with the light on the edges of these rows of tight curves, they are related to the curve of the stars, and the nebula above. There is a lovely diagonal formed by the trees going from the lower right of the canvas towards a point in the center of the painting near the horizon, almost like a path to the sky.

1. In and Out, Point and Line in Painting—and in Us

In Aesthetic Realism lessons, as Eli Siegel talked to a person, he brought the structure, the grandeur of the whole world to the seeing of a particular question. He explained the cause of a fear I had so truly that I never had it again. I was to see that In my desire to be self-contained, to keep myself to myself, I was not honoring the best thing in me—my desire to be expansive, to go out to the world and to be affected by it. He explained: “Every perception has order and disorder in it. The idea of being contained and trying to get out is frightening to Miriam Mondlin.” And he related these opposites in myself to the art I cared for most: “Every painter,” he said, “is trying to get out of the canvas or be contained. It arises,” he said, “from a philosophic idea—in and out; point and line.”

I am thrilled to see that every square inch of this painting shows Van Gogh was “trying to get out of the canvas,” and “be contained”—and both have the same purpose—to see the world truly.

A rising mist above the sloping forms of the mountains, hugs the mountains. Yet through it, the mountains expand and rise in space. Eli Siegel taught me that through seeing my relation to things, I would be more myself. This principle is what we see in Starry Night.

In another Aesthetic Realism lesson, Mr. Siegel said:

Every person is a center looking for an area and illimitably flexible circumference; if that area and circumference are brought to that center, that center is safe—because a person is saved when self while remaining self, as a center does, takes on this expansion in fact.

2. A Star Is Center and Circumference

This is what we see in Van Gogh’s painting. One of the most beautiful things about this painting are the stars. With all their expansive radiance they are all circular. There are 11 stars, and the center and area of each star is different; yet each consists of some warm yellow, some having more white, some less. All have, too, the blue of the sky, yellow ochre and black of earth.

Look at the star at the top of the upper left. The chrome yellow center is surrounded by a yellow band then by a thinner, darker yellow band that simultaneously contains the center and enlarges. Then, as it continues to expand, its area is added to with short, white, blue, blue-green and yellow strokes until they mingle and blend with the dark blue-black sky surrounding this star. Van Gogh has painted each star as he himself and every person hopes to be: a center—as Eli Siegel explained to me—and an illimitably flexible circumference. And the lines Van Gogh painted throughout the stirring sky connect every star to everything else in the picture. Nothing is isolated; each star is distinct and also becomes what surrounds it.

Another way Van Gogh joins things in this painting is through allowing the pale yellow canvas to show through. In this night scene, light is within and comes forth in everything—in the sky, in the cypress, in the houses, in the mountains, the trees, the mist—everywhere! The pale yellow glow is related to the intense yellow in the stars, which are so thickly painted, and seem so much on the outside. The houses with their snug, inward quality have bright yellow lights in them, like these stars. So the bright rectangles of light within the houses are like the expanding points of light in vast space. The contained and expansive are made one.

There was no limit to Eli Siegel’s desire to understand both the feeling of a human being and the world itself. In 1960, as Mr. Siegel said to me in a lesson, “The universe is not big enough to find out who you are. Everything tells you something of who you are,” he was deeply commenting on what Van Gogh, one of the greatest artists of any century was hoping to find as he looked for meaning in what he called “My starry sky.”

This talk is from the historic series Art Answers the Questions of Your Life, given at the Terrain Gallery in NYC.