By Anthony C. Romeo, AIA, NCARB

Early in my career, while working on designs for a new building lobby requiring Italian marble, my supervisor asked me to travel to Italy to visit the quarry and select marble for the project. When I mentioned this in an Aesthetic Realism class, Ellen Reiss, the Chairman of Education, asked what qualities I cared for in marble. I had worked with marble and knew some of its many varieties. Ms. Reiss asked about opposites central to its beauty: “Do you think marble is warm and cool at the same time, and there can be a quality of warmth in the coolness?” I said “Yes!” I’d never thought of marble in this way!

She suggested that I find five instances of marble used in a way I saw as beautiful, and she said: “Try to see with each one why it’s beautiful. And you can ask, what does that beauty have to do with the marble itself, as well as what’s done to it.”

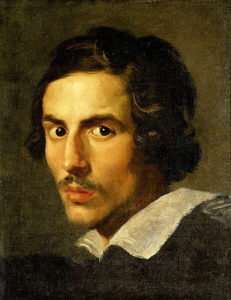

This was the beginning of my looking into the meaning of the materials I work with as an architect. And I thank Ellen Reiss for the way she’s encouraged me to ask: What do art and life have to do with each other? One of the artists I’ve come to love as a result of my study is the great Baroque sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini. (This is an early self-portrait.)

As I studied his architecture and sculpture, I was thrilled to see how deeply both are explained by this groundbreaking principle, stated by Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” The opposites of warmth and coolness, so central in the life and work of Bernini, bring up ethical questions which are crucial in every person’s life.

1. Warmth & Coolness: Can We Be Intense with Accuracy?

As a young man, I could be very intense and irate—particularly when I sensed some injustice to me. Friends called me a “hothead.” But because I didn’t like thinking about other people and what they deserved, my intensity was often inaccurate, and I didn’t like being deeply affected by things, which made me cold. In The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, Ellen Reiss wrote:

“Coldness is an aspect of contempt. We feel we have ourselves in a kingly or queenly fashion if nothing can move us….We despise ourselves for being cold, we ache from our coldness, because our greatest desire is to like the world, to feel our living relation to every thing and person.”

The study of Aesthetic Realism enabled me to feel a deep and vivid sense of relation to other people, and for this I will be eternally grateful. It is what people throughout the centuries have longed to feel, including the great Gian Lorenzo Bernini. In his art, he achieved an astonishingly beautiful relation of intensity and accuracy: he could make cool marble take on the subtlety and warmth of flesh. In his life, however, he could be hot and cold in a way that I think troubled him deeply.

Born in Naples on December 7, 1598, he was about six when his family moved to Rome so his father could work as a sculptor, decorating a chapel for the Pope. As a teenager, Bernini studied the art in the Vatican, and his talent as a sculptor was soon noticed: he received his first commission from the papal family at 16. His career would span over 70 years, and as art historian Rudolph Wittkower writes, “It was he more than any other artist who gave Rome its Baroque character.”

In a great lecture Mr. Siegel gave about sculpture, he spoke about the fight between those who wanted sculpture to be warm and expressive and those who felt it should be cool, abstract. “Take the sculptor Bernini,” he said. “[His] St. Theresa is ecstatic…and you would think that sculpture was the warmest matter going.”

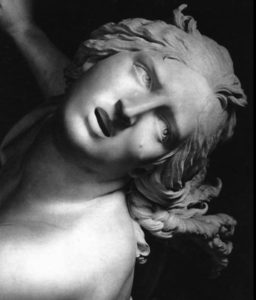

I’ll say more about this magnificent sculpture, but first, I’ll look at some earlier work. The Anima Dannata, or Damned Soul, was made when Bernini was about 20. His son and biographer, Domenico Bernini, writes that his father once put his own leg into the fire so that he could study and produce more exactly an expression of intense pain. Whether this is true or not, it is clear that Bernini studied his own features for this sculpture, which expresses rage and pain. You can almost hear the Dammed Soul crying out, and feel the heat from his flaming locks.

Yet with all its explosiveness, this face is carefully molded. Clearly Bernini wanted to know what was going on in the depths of this damned soul. And the fact that it is mounted on a breastplate that is almost a perfect oval brings a beautiful calming composition to the intensity of this work. A sense of structural stability is also achieved through the vertical line of the pronounced neck muscle, and the strong horizontal of the breastbone.

Bernini got marble to express things it never had before. Arthur Ludlow wrote in Smithsonian: “He sought to imbue cold, inanimate stone with warmth, movement and life.” He worked intensely, sometimes seven hours at a time without interruption, and a friend described an almost incredible relation of accuracy and intensity when he told of the artist carrying on a lively conversation while “crouching, stretching,…marking the marble with charcoal in a hundred places and striking with the hammer in a hundred others.”

To show something of the variety of Bernini’s works—and the way warmth and coolness are in each—I quote critic Howard Hibbard:

“Bernini’s early development is crowned by three great works…: the Pluto and Persephone,

“the Apollo and Daphne,

“the David…

“[T]he Pluto…stuns us from the outset with its amazing virtuosity….Bernini seems bent on pushing the resources of marble sculpture to their extremity…[His] stupendous technique as a marble cutter seemingly allowed him to model the obdurate material as if it were dough…The texture of the skin, the flying ropes of hair, the tears of Persephone, and above all the yielding flesh of the girl in the clutch of her divine rapist initiate a new phase of sculptural history.”

Bernini gave careful thought to presenting this intense moment, the rape of Persephone, when Pluto, in love with the beautiful girl, steals her away from her mother, Ceres, to his realm in the underworld. From the front we see Pluto carrying Persephone while she struggles, pushing him away, as he tightens his grip, his hand sinking into her soft flesh.

From the side we see Cerberus, the three-headed dog, barking, as Persephone cries out to her mother, tears streaming down her face. You feel the struggle, Persephone’s anguish, and Pluto’s overwhelming power.

In this breathtaking work Bernini brought together warmth and coolness, intensity and accuracy, in a way that changed the art and culture of the 17th century. As Ellen Reiss wrote:

The authentic coolness we want, and which Aesthetic Realism enables a person to have, is the coolness of art: the coolness that is form, composition, order. This coolness does not come from contempt. It comes from seeing an object with such fullness of respect that one’s emotion has, inevitably, logic and control.

The coolness of form is in the way Bernini composes Pluto and Persephone. Within all the tumult there is a diagonal line that can be drawn from the top of Persephone’s head down into Pluto’s right leg, and the placement of Cerberus supports the graceful, anguished Persephone.

This is the message of art: that warmth and coolness don’t have to fight, that they can be one.

2. Warmth and Coolness in Love

In 1635 Bernini met Costanza Bonarelli, the wife of an assistant in his studio. His portrait sculpture of her affected people, notably because of Costanza’s soft parting lips, “about to speak,” and the stillness of her expression.

It evoked much controversy, and, according to historians and biographers, the two had a tumultuous relationship. Rudolph Wittkower writes that when Bernini learned Costanza was also having an affair with his brother, he flew into a rage, grabbed a knife and went in pursuit of them. His mother begged Pope Urban VIII to intervene, which, fortunately for all, he did.

The artist, who could present intensity with such astonishing control in his art, had a different purpose in love. It was not to honor the world, with that resplendent oneness of coolness and warmth he went after in Pluto and Persephone, but to have his way with it, and his contempt made for a relation of intensity and coldness he had to despise himself for.

As a young architect, I was passionate about my work, and would meticulously draw and redraw designs until every line was perfectly rendered. But I could also be driven in a very sloppy way, particularly when it came to women. I once put my fist through a wall, and at another time ran my car through the fence around a girl’s home, after her rejection. I was often furious one moment and humbly penitent the next, and this shuttling back and forth worried me very much. I’m tremendously grateful this changed through my study of Aesthetic Realism. In a consultation I had one Valentine’s Day, I tearfully told my consultants that my girlfriend broke up with me and they asked:

Consultants: Do you think the only way to salvation is having a beautiful woman show care for you? And if she doesn’t you’re a failure?

Anthony Romeo: Definitely.

Consultants: And therefore you should be in a rage?

Anthony Romeo: I don’t know. But why couldn’t she be happy with me? I never felt I had her.

Consultants: Do you think your purpose with her was good?

Anthony Romeo: No, I don’t.

Consultants: You’re hard hit because you didn’t get your way, but do you think it can be useful to you?

Anthony Romeo: I hope so.

I came to see that with all the emotion I thought I had about a woman, I was deeply cold: I was thinking about myself, not the woman. I saw her as a trophy, someone I could own and manage, and gave myself the right to be furious when she didn’t bend to my wishes. I wasn’t interested in knowing the depths of her feelings and thoughts. In consultations, and in the Aesthetic Realism lesson I was honored to have with Eli Siegel, I was encouraged to respect the dimensions of a woman’s mind, and want to know her thoughts. Because of this, I was able to fall in love with and marry Karen Van Outryve, Aesthetic Realism consultant and poet. And now, in professional classes taught by Ellen Reiss, we are both able to learn what it means to have authentic warmth, and the coolness of accuracy or exactitude in our marriage, and I can honestly say my feeling for and thought about my wife are deeper every day.

3. Architecture and Life

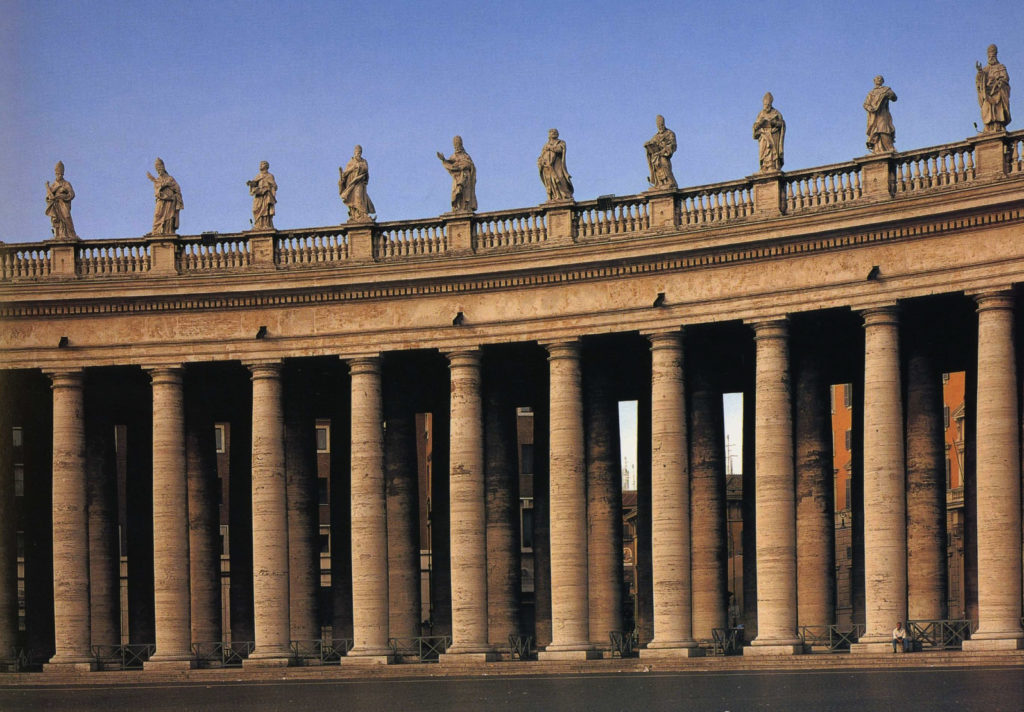

As his career went on, Bernini’s art included architecture and painting as well as sculpture. This is the Vatican’s Piazza San Pietro, likely his most well known work. The church had been increasingly criticized for its wealth, and wanted a design for this plaza that would appear welcoming to people.

Bernini rejected an earlier trapezoidal scheme in favor of an oval form, which is softer. He has two colonnades stretching out, like arms, to welcome people within. The porticoes surrounding the plaza are actually four columns deep, comprising two side aisles for the public—offering shade from the sun and shelter from inclement weather—and a center aisle for the pope’s processional.

As a visitor walks through the plaza, one column after another is revealed. Bernini wanted this structure to be both cool and warm, to represent the grandeur and power of the church but also be friendly—and for the last 300 years it has done so.

As a visitor walks through the plaza, one column after another is revealed. Bernini wanted this structure to be both cool and warm, to represent the grandeur and power of the church but also be friendly—and for the last 300 years it has done so.

In the Sant’Andrea al Quirinale Chapel, Bernini created an integrated masterpiece of architecture, sculpture, and painting. T.A. Marder calls it “the unquestionable jewel of Bernini’s church architecture.”

Bernini’s son once found him sitting in the chapel, and his father confessed that he had for it “a special satisfaction in the bottom of my heart, and often for relief from my weariness I come here to console myself with my work.”

The Sant’Andrea chapel is small, approximately 80’ wide by 55’ deep. There is something personal and intimate in the compact size, yet you feel all the world is present. The oval shape, the hidden sources of light, and the dome give this chapel a sense of grandeur and space.

In Is Beauty a Making One of Opposites?, Eli Siegel writes about Impersonal and Personal:

“Does every instance of art and beauty contain something which stands for the meaning of all that is, all that is true in an outside way, reality just so?—and does every instance of art and beauty also contain something which stands for the individual mind, a self which has been moved, a person seeing as original person?”

The entire building is a stage for the story of St. Andrew’s ascension. For example, Bernini provides a skylight out of view from all but the priest conducting the service, through which angels and happy putti (or cherubs) lead Andrew to heaven, and here upon a window cornice at the base of the great gilded dome we see three playful putti. The effect of the journey, in perfect perspective, is one of joy and divine inspiration.

Then there is that great dome, the ten ribs of which correspond to the columns and pilasters below, intersected by windows. The ribs are narrow, emanating from the lantern like a starburst and culminating between the windows flooded with the heavenly light. I think Bernini felt composed as he sat in the chapel of Sant’Andrea, because here he felt warmth and coolness as one, the stark elements of classical architecture and the warm embrace of heavenly light at once.

How amazing it is that cool stone conveys warm, pulsating flesh—as St. Theresa appears to float upon the cloud she rests on! The young angel looks upon her with a sweet, loving expression as he holds the hem of her cloak and prepares to pierce her with the arrow of God. Her body yields utterly, with hands and feet limp, but the folds of her robe are in great motion and they are weighty, giving her a sense of power along with lightness and warmth. St. Teresa welcomes this intense piercing—she knows it is deeply kind and liberating.

As Mr. Siegel said of it: “You would think that sculpture was the warmest matter going.”

I think Bernini felt this sculpture stood for something he hoped for in himself. I think he longed to hear the questions Aesthetic Realism asks: Are we hoping that our sense of impermeability, a certain frigid response to things, be opposed? Is there a desire in us, which this sculpture stands for, to be deeply affected by reality outside ourselves, not coldly immured within ourselves? The answer of art is a resounding Yes! And one of the reasons I love Aesthetic Realism is because it criticized my conceit and changed me from a cold, intensely selfish person into one who can think about and really care for others. And it can do this for everyone!

ANTHONY C. ROMEO is a Design Director with a NYC Design and Construction Agency. He has over 30 years of professional practice, including design and project management for William Bodouva & Associates with whom he designed the award-winning USAir Terminal at New York’s LaGuardia Airport. Since “Superstorm Sandy” in 2012, Mr. Romeo served the City of New York in a leadership role, first rebuilding beach structures and parks for the NYC Parks Department and as Design Director for the federally funded “Build it Back” program building resilient homes in communities affected by the storm.

Mr. Romeo is grateful to have studied Aesthetic Realism with its founder, Eli Siegel, and to continue his studies with the Chair of Education, Ellen Reiss. As an Aesthetic Realism associate, he’s given papers in public seminars, including on architects Frank Gehry, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Gerrit Rietveld, Louis Kahn, Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, Andrea Palladio, Sir Christopher Wren, and others. These papers have been given as well in the series “Architecture and You,” presented with his colleague Dale Laurin at public libraries throughout the NYC metropolitan region for over eight years. “Architecture and You” is also the title of a class for young people—based on Aesthetic Realism principles—that he has taught at the Children’s Aid Society and at P.S. 41 in Manhattan. He currently teaches architectural history as an adjunct assistant professor at CUNY’s College of Technology.