Central Park—Its Beauty and Ethical History

By Dale Laurin

Central Park is the first public park in America and still one of the most beautiful, enjoyed by millions of people every year—(hovering with your cursor will pause the slideshow)

Where else can you spend a day doing everything from playing ball to hearing an impromptu concert, seeing and smelling flowers, riding a carousel, picnicking, looking at an obelisk from ancient Egypt, rowing a boat across a lake whose surface reflects trees, clouds and skyscrapers, climbing a boulder or a life-size sculpture of characters from Alice in Wonderland, bird watching, exploring a castle, then lounging in the grass—all a subway ride away, and all for free?

I see Central Park, in its unity and variety, as an important work of art. It illustrates the principle which is at the basis of my work as an architect, stated by Eli Siegel, founder of Aesthetic Realism:

“All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

I’ll show that the way this park puts reality’s opposites together is beautiful the way a painting or piece of music is beautiful—and further, that through the knowledge of Aesthetic Realism, it can be useful to our very lives.

Oneness and Manyness

In his 15 Questions, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, Eli Siegel asks:

“Is there in every work of art something which shows reality as one and also something which shows reality as many and diverse? —must every work of art have a simultaneous presence of oneness and manyness, unity and variety?”1

These opposites were fundamental to the original vision of a “central park” for New York City had by its designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. As Olmsted explained, Central Park was to have:

“all classes largely represented, with a common purpose, each individual adding by his mere presence to the pleasure of all others, all helping to the greater happiness of each.”2

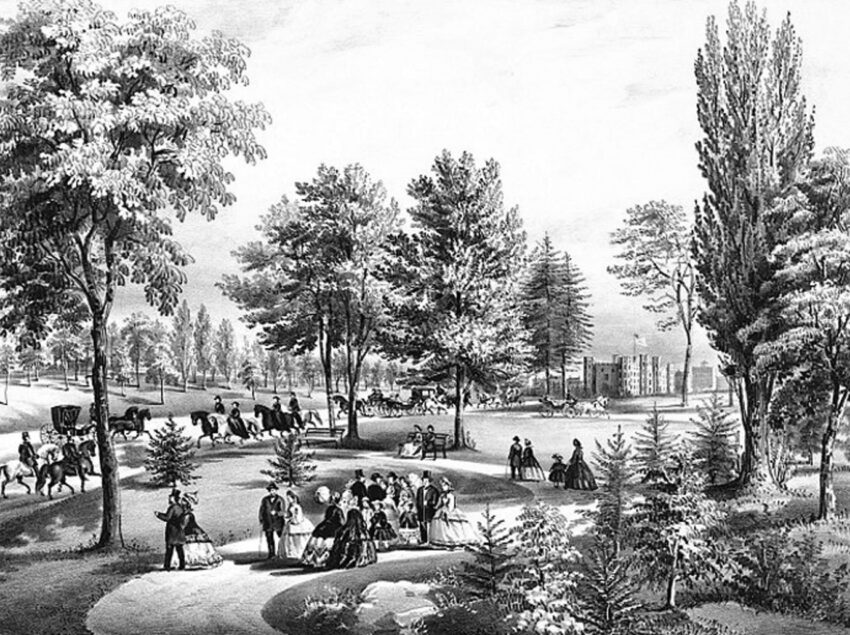

In the mid-1800s, most New Yorkers labored long, hard hours, lived in crowded, stifling tenement houses, and unlike the rich, couldn’t afford the time or money to vacation in the country. The Park designers sought to create a feeling of the country in the city, a place where workers and their families could come to refresh their bodies and minds.

Their tremendous achievement is that the park they created encourages this kind purpose through its thoughtful design—and centrally through the way it puts together oneness and manyness.

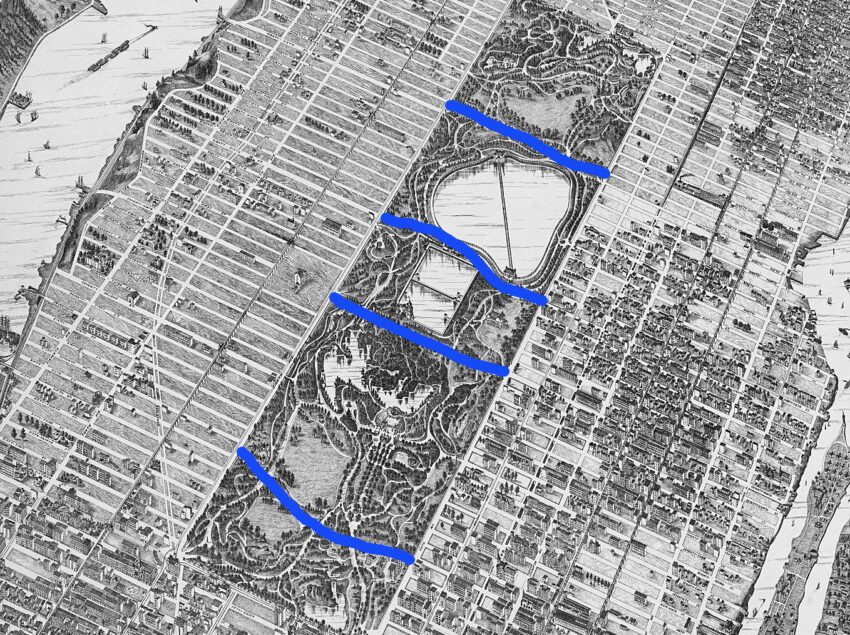

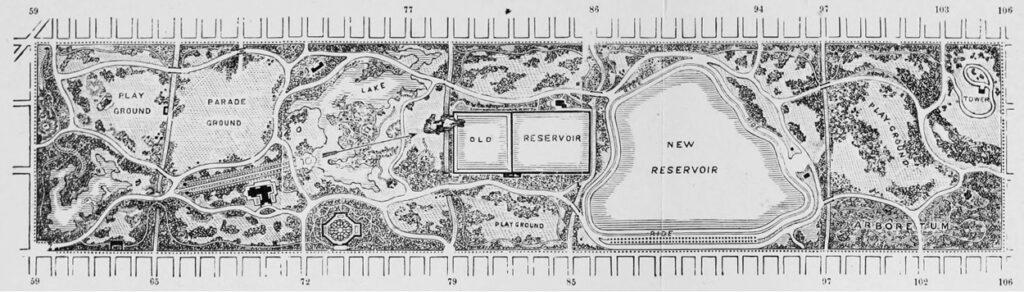

A seemingly insurmountable obstacle facing the designers was the fact that city officials stipulated that the two-and-a-half-mile long tract of land they assembled would have to be subdivided by four cross-streets to allow horse-and buggy traffic to cross east and west unimpeded. These streets—67th, 79th, 86th, and 96th—would have, in effect, made for five small parks, not one large park with the rural feeling the designers wanted, and for park-goers, getting from one parcel to another would have been hazardous.

But Vaux and Olmsted came up with the imaginative idea of ramping the streets below the level of the park and placing park roadways and paths atop wide bridges planted with abundant trees, shrubs and plants.

They wanted to make the cross streets scarcely noticeable to park goers, creating the feeling of one, unified park arising from the five sections, enabling people to freely traverse unimpeded from 59th St. all the way to 110th, if they liked.And they succeeded!—after 166 years of growth, the vegetation hides the roads so well, you can be unaware that cars and taxis are actually speeding by a few yards away.

The Park itself is composed of many distinct parts, each with its own unique character, yet these flow into one another with no distinct boundaries. For example, starting at the south east corner of the park, you can stroll around the rustic Pond, promenade the length of the stately Mall under towering elms, descend the grand staircase at the elegant Bethesda Terrace, cross a lake atop Bow Bridge, skirt the wild, thickly wooded Ramble, pass the sunny, expansive Great Lawn, circle around the Reservoir, cross the North Meadow to the formal Conservatory Gardens, and end at the bucolic Harlem Meer in the northeast corner!

Yet with all this variety you feel it’s a continuous experience—with every element adding to the next and all contained within one large, neat, 843-acre rectangle, right in the middle of America’s largest metropolis.

The Opposites in Ourselves

The opposites of oneness and manyness, unity and variety—which Central Park puts together so well—are also opposites every person wants to make sense of in ourselves. I was fortunate to learn about this in an Aesthetic Realism lesson I had with Mr. Siegel. Like most people, I felt there were many different things going on in my life, with little sense of coherence among them. I was a son, a brother, a roommate, I was an architect and a trustee at the church I attended, I cared for music, particularly Beethoven, and I had just begun to date a young woman, Barbara Buehler, who I’m happy to say has been my wife now for many years.

Mr. Siegel asked me this surprising question: “What relation do you think Beethoven has to architecture?”

Dale Laurin: “Well, I think he has a beautiful relation of freedom and order that good architecture has, too.”

Eli Siegel: “Do you think that every composition in music is in a sense a construction?”

DL: “Yes, there’s a going for something organized.”

ES: “And are you an organization?”

DL: “Not as well organized as I could be.”

ES: “The large thing in organization is many things working as one. Do you believe right now all of your body is working as one? There’s a relation between your toes and your eyes? Also between your fingers and your toes?”

DL: “Yes!”

I learned that what has a person feel truly composed and unified is using the different aspects of our lives for one purpose—our largest purpose, which Aesthetic Realism explains is to like the world. With all its confusion and injustice, the world can honestly be liked, because it has an aesthetic structure. The fact that everything is composed of opposites—like one and many, rest and motion, inside and outside—means that we are not only different from everyone else, as I had felt; we are also related. The way the various elements of Central Park add to each other then, shows how we want to be and how we need to see people different from ourselves—with the respect and kindness they deserve.

The Coming to Be of the Park: Private & Public

The idea of public parks originated in 18th century England, where landscaping was designed for great country estates that put together formal and informal, planned and natural elements. In the 1840s and ’50s, a group of visionary New Yorkers felt that a large green open space like these was greatly needed—not in the country for the exclusive use of a privileged few, but right here in this densely built-up, rapidly growing city, convenient for everyone to enjoy. Through their advocacy, in 1853 the NY State Legislature authorized the city to purchase land to develop a park.

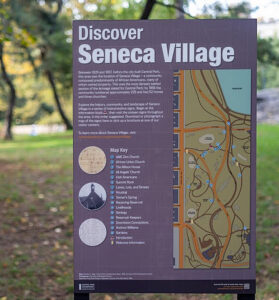

While the designated area north of town was mostly undeveloped , it also included Seneca Village, home to several hundred people, mainly freed African Americans.

In the effort to get these citizens to leave this land, which most of them legally owned, they were horribly subjected to racist attacks. Those who didn’t accept government buyouts were evicted—using eminent domain—and the village was leveled.

This was an inexcusable, shameful injustice, and I’m glad at least that now it has been recognized as such. One redeeming fact is that their sacrifice wasn’t for a private development but for a public park, created for all New Yorkers to use—including their children—and generations who have followed.

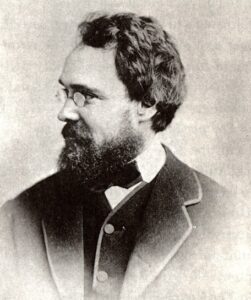

An early supporter of the park was Calvert Vaux. Vaux, who lived from 1824 to 1895, was a London-born architect and landscape designer who immigrated to the US. He opened an office in New York, and over the next 40 years designed for this city he loved and called home several notable landmarks, including the Jefferson Market Courthouse at 6th Avenue & 10th Street (now the Jefferson Market Library).

While Vaux was pleased New York would finally get a public park, he was rightly critical of the formal design proposed by Egbert Viele, the engineer appointed to plan the park—a design in which the four transverse streets I spoke about were shown cutting through—and, in his opinion—ruining the park. With others, Vaux successfully urged officials to hold an open competition to elicit and select the best design. At this time, when landscape design was not even recognized as a profession, let alone taught, Vaux, who had previously worked as a landscape designer, was one of the most capable persons for this task.

He decided to team up with Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), a farmer and journalist who had been appointed superintendent of construction for the park some months before. While Olmsted had visited England and was impressed by the public parks there, he had no experience in landscape design. But Vaux recognized his potential, and he respected Olmsted’s passion about the land and about what people deserved—expressed in two books Olmsted wrote about his travels through the South, including firsthand accounts of the horrors of slavery, which he abhorred.

Working evenings in Vaux’s home, the two men created what they called the Greensward Plan that won the competition and gave birth to a whole new art form that Vaux would later call landscape architecture.

The Kindness—and Ethics—of Central Park

From today’s perspective, it’s hard to conceive how revolutionary Central Park was. In the 1850s, there were virtually no large public parks in American cities. The very idea!—that in the middle of this fast-growing city of banking and commerce, a huge parcel of prime real estate the size of 153 city blocks—

—was to be owned, not by individuals to build tenements and factories for their personal profit, but by and for the use of every New Yorker, including the poorest, was astounding to most people and infuriating to many. For it profoundly challenged what some saw as the cherished right of private ownership at a time when profit economics—epitomized by entrepreneurs such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and John Jacob Astor—was approaching its zenith.

I believe Central Park and every public park to follow is part of what Eli Siegel explained in 1970—”ethics is a force” in the world, and it is bringing to an end what he called “the much-touted mode of American industry,”3 “that toughest, most inconsiderate of activities”4—in which the majority of people work to make money for a few. He showed that an economy based on profit is inherently unjust because it encourages people’s contemptuous desire to own the world, rather than to know it. As Mr. Siegel explains in his book Self and World:

I believe Central Park and every public park to follow is part of what Eli Siegel explained in 1970—”ethics is a force” in the world, and it is bringing to an end what he called “the much-touted mode of American industry,”3 “that toughest, most inconsiderate of activities”4—in which the majority of people work to make money for a few. He showed that an economy based on profit is inherently unjust because it encourages people’s contemptuous desire to own the world, rather than to know it. As Mr. Siegel explains in his book Self and World:

“The possessor has felt that it was more important to feel that a tree was owned by him than to feel that he knew what the tree was and what it could mean. And he has let the ownership of a tree, or grass, or a field, take the place of being fully affected by these things in nature. The artist has been forced to possess…forced to compete, but as artist he was not after possession…or competition.…He has come to power by undergoing the might of things and giving them form through his personality.”5

Olmsted and Vaux’s desire to know and be affected by the land of this tract of earth and by what New Yorkers deserved, inspired them to give the land a new, beautiful, and kind form. They wrote in a report:

“The purpose of a public park is to provide a place where towns-people can regain the energy they had expended in labor, for without the recuperation of force, the power of each individual to add to the wealth of the community is also soon lost.”6

And they described what such a park must offer:

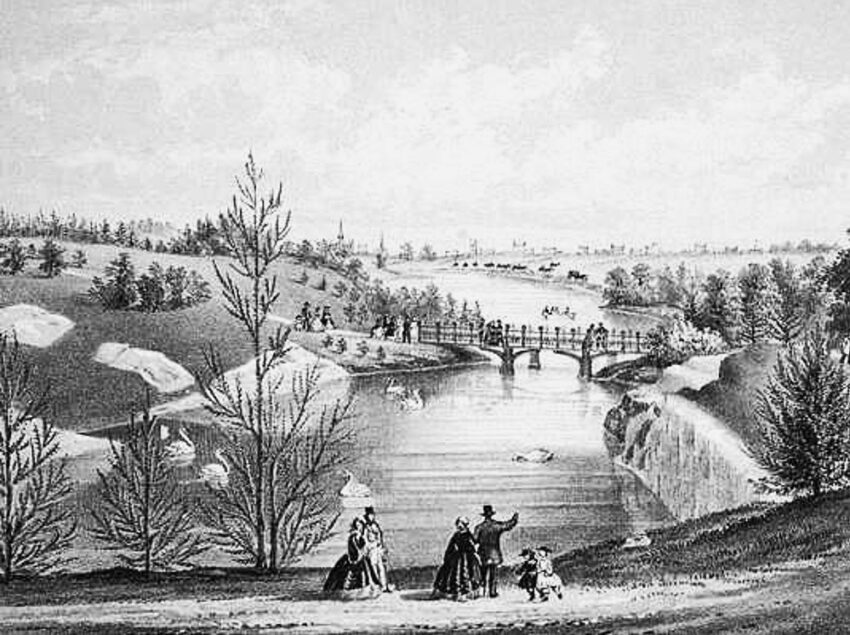

“pastoral scenery [consisting] of ‘combinations of trees, standing singly or in groups, and casting their shadows over broad stretches of turf, or repeating their beauty by reflection upon the calm surface of pools…the predominant associations are in the highest degree tranquilizing and grateful, as expressed by the Hebrew poet: He maketh me lie down in green pastures; He leadeth me beside the still waters.’”

This is beautiful. The designers had a conviction that hard-working people would be strengthened—both rested and energized—-by experiencing trees “standing singly” and “in groups,” solid turf and reflective waters. This points to the opposites of repose and energy, one and many, and to what Aesthetic Realism would explain a century later: that seeing opposites together in the world can have these same opposites more composed in ourselves, making us stronger and happier.

Sameness and Change; Firmness and Flexibility

Many people think that Central Park is largely natural, that—as the famous NY Journalist Horace Greeley said on seeing it for the first time, “Well, they have left it alone better than I thought they would.”7 But if Vaux and Olmsted had left the land north of 59th St. as they found it, instead of this vista—

we would have this—

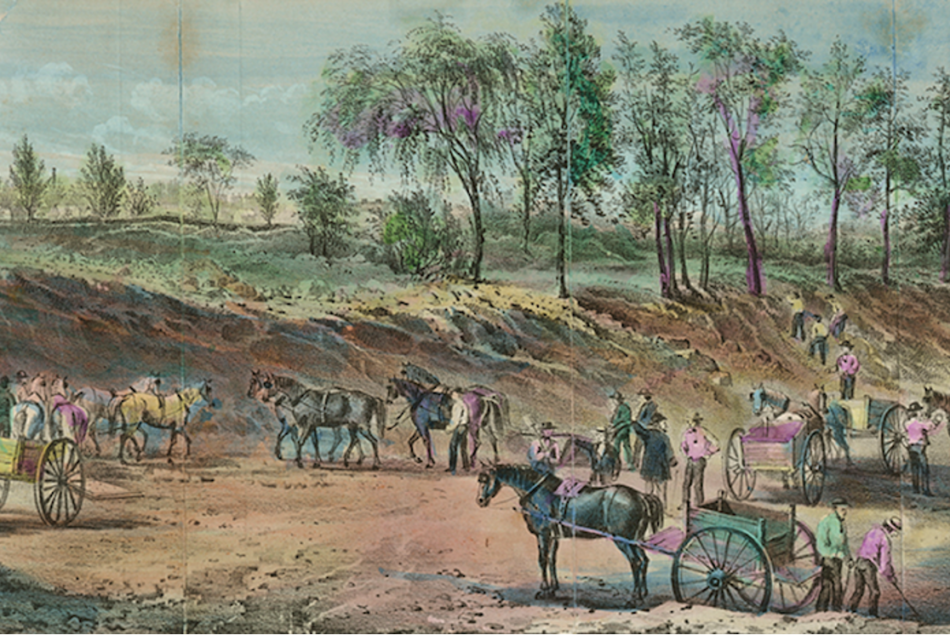

Hard as it is to believe, Central Park is more a work of art than a product of “mother nature,” and one that called for tremendous effort and made for tremendous change.

Some of what this took in, I’m grateful to have learned from my colleague, consultant and urban planner John Stern. He wrote, for instance, that in Olmsted’s role as construction superintendent, he mobilized a workforce that numbered hundreds of men who cleared away refuge dumps, dredged swamps, and moved tons of earth and rock, excavating—not only for the submerged cross-streets—but for miles of drainage pipe. They filled in and prepared the soil, built bridges and park structures, laid down pathways and roads, and planted thousands of trees, shrubs, and plants on this largely barren site.

However, the designers didn’t change everything. Writes Mr. Stern,

They carefully studied and worked with the topography and existing elements of the site, leaving—for instance—many of the magnificent rock outcroppings and rugged terrain intact, as natural features. At the same time, they softened the effect of the rocks through introducing lakes and ponds, meandering walks, and a rich variety of plantings, much of which was planned by the renowned Austrian landscape designer Ignaz Pilát. The result is what Mr. Siegel called a ‘planned wilderness’ that is both natural and urbane, rugged and people-friendly at once.

The Structures of Central Park: Assertive and Yielding

A common mistake people make is to feel it’s weak yielding to other people and things—that to take care of yourself you have to be assertive, have your way. In doing so, however, we often feel mean and cold; I sure did. But as Mr. Siegel writes in his book Self and World, art shows these opposites don’t have to fight:

“Through merging with things, the artist has deeply been controlled by them. He has come to power by under-going the might of things and giving them form through his personality.”8

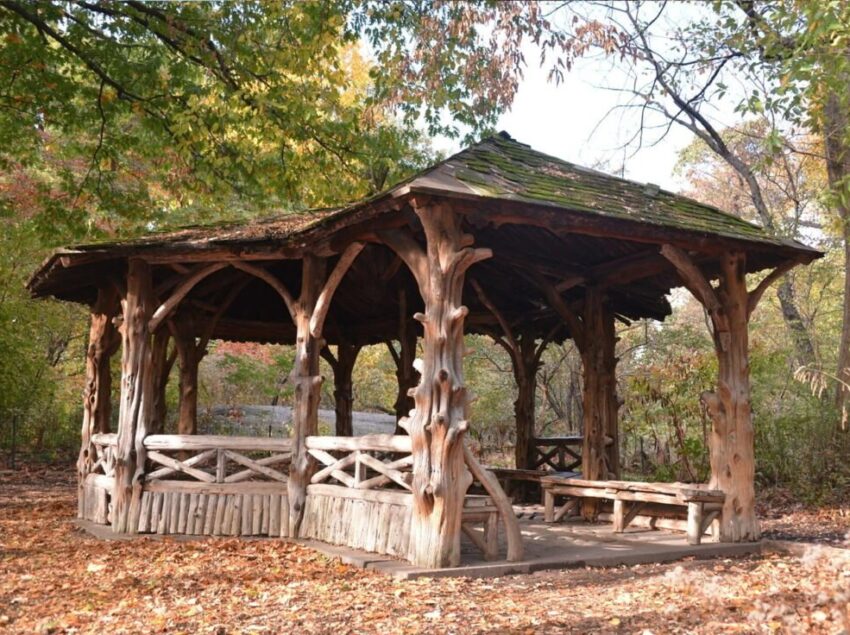

Providing rich evidence for this are the dozens of imaginative bridges, pavilions, and arbors that Calvert Vaux designed throughout Central Park.

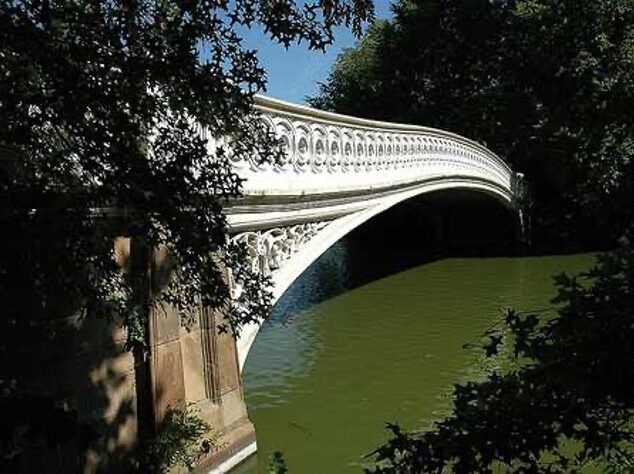

These structures don’t assert themselves or the architect’s ego in competition with their natural surroundings; they seem inspired by them, and so join with the landscape as if they had always been there: from this whimsical branch-like shelter and this charming rustic bridge, to the grandeur of the Terrace staircase with leafy carvings by Jacob Mould, from Belvedere Castle that seems to rise out of the rock—

—to Vaux’s masterpiece, the sublime Bow Bridge. See how low and lovingly it hugs the earth even as it effortlessly leaps across the lake like the most graceful deer—strong, dignified, and proud in its relation to the world that is both around it, and—through that arching line of circular, sun-dappled openings—within it. By “undergoing the might of things,” Vaux got to his most powerful expression, which is all the greater for its simple eloquence.

Central Park will surely continue to attract New Yorkers and visitors from around the world for many years to come. And while people will seek its fields, flowers, and lakes as an idyllic retreat from office pressures and crowded, noisy streets, the park’s crags and thorns and reflections of office towers in its lakes should remind us that Central Park is a part OF—not apart FROM—the rest of the world, and related to everything through the opposites. I think Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted would want their creation to be a means of people seeing all reality more accurately and kindly, something Aesthetic Realism beautifully encourages. This will truly add, as Olmsted wrote, “to the pleasure of all” and “the greater happiness of each.”9

Footnotes:

1. The Fifteen Questions, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? by Eli Siegel were first published by the Terrain Gallery in the announcement of its opening, February 26, 1955. Reprinted in the following periodicals: Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism, December 1955; Ante, 1964; Hibbert Journal (London), 1964.

2. Olmsted, Vaux & Co., “Report of the Landscape Architects,” Board of Commissioners of Prospect Park, Sixth Annual Report (1866)

3. Eli Siegel, Goodbye Profit System, Definition Press (New York, 1970), 9: from “We Have with Us the Triumph of Good Will,” May 22, 1970 lecture by Eli Siegel reported on by Alice Bernstein

4. Ibid., 1

5. Eli Siegel, Self and World, Definition Press (New York, 1981), 280-281

6. Olmsted, Vaux & Co., “Report of the Landscape Architects”

7. Frances R. Kowsky, Country, Park and City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux, Oxford University Press, (New York, 1998), 307

8. Siegel, Self and World, 280

9. Frederick Law Olmsted, from Public Parks and the Enlargements of Towns, Arno Press (New York, 1970); Read before the American Social Science Association at the Lowell Institute, Boston, Feb. 25, 1870.