By Dale Laurin, RA

Presented at the 2013 Annual Conference on Architecture at the Athens Institute for Education & Research, Athens, Greece. Originally given at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, NYC.

The Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who lived from 1887 to 1965, is widely regarded as one of the most important architects of the 20th century. I believe his life and work are centrally explained by Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy founded by the great American poet and critic Eli Siegel (1902-1978), who stated: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” This groundbreaking principle provides the criterion both for beauty and for happiness and self-respect in people’s lives. It states that a work of art—in this instance, architecture—is successful in proportion to how imaginatively, richly it puts together opposites, such as heaviness and lightness, surface and depth, freedom and order. It also shows that we can learn from art how to compose these same opposites in ourselves.

The sculptural power of Le Corbusier’s buildings stirred me from the first photographs of them I saw as a student. The structures he designed range from individual homes, like the 1908 house in Paris commissioned by the brother of American writer Gertrude Stein,

to the master plan and several government buildings he designed for Chandigarh, India, in the 1950s.

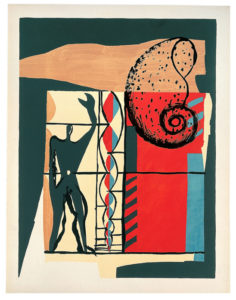

He also wrote over 40 books and was an accomplished painter and furniture designer. Several of his chairs are seen as modern classics and are still popular today.

Le Corbusier designed only one building in the US, this 1964 Visual Arts Center at Harvard,

but his impact—both good and bad—on modern architecture here and abroad is immense. Works like his Villa Savoye built near Paris in 1929, one of his works I will be speaking about, with its continuous window bands and elegant white geometry, have influenced the design of homes and skyscrapers alike. His “Towers in the Park” planning concept of tall, massive residential structures surrounded by open space inspired urban renewal projects from coast to coast in the 1950s, only to be widely condemned by the 1970s. The UN Secretariat Building is based on a Le Corbusier design. And so is one of the most hated buildings in Boston—their City Hall, derived from Corbusier’s La Tourette monastery, whose rough, unfinished concrete walls inspired an entire style of architecture, appropriately called brutalism.

As I’ll show, Le Corbusier’s life and work are particularly valuable in studying the debate that goes on in every person between the opposites of warmth and coolness. Eli Siegel described a hurtful form of coolness in an early issue of the journal The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known:

In this world, men and women often find refuge in coldness. Coldness, quite clearly, is allied to contempt; and…contempt for the world is seen by man as a safeguard of himself….Any time we can give a cold shoulder to something, our self-stock rises.

Mr. Siegel defined contempt as “the lessening of what is different from oneself as a means of self-increase as one sees it,” and he showed that contempt is our greatest temptation and the cause of all human cruelty. Our constant debate is whether we’ll be important through having contempt or through wanting to like and respect the world, which Aesthetic Realism explains is our deepest desire and the source of all art.

1. The Debate Began Early in Me and in Young Charles-Edouard

Like many children, I used my parents’ excessive praise of me to feel I was special, better than other children and people as such. This is why, even as I joined the youth group at church and the Russian club at school, I was rarely moved or excited by things. My hope to know and be affected by people fought with the feeling that everyone should praise me as my parents did. My largest emotions were about architecture, but buildings didn’t flatter me. In college I was asked to give my thought and imagination to them and to the people I designed them for but didn’t like. Increasingly, I felt tired and uninspired.

I also worried that I was incapable of having large feeling about anything—something I spoke about in an Aesthetic Realism lesson I had with Eli Siegel in 1978. Said Mr. Siegel: “I don’t think anybody would stop you from having a big emotion. The thing is, do you feel it’s good for you to have a big emotion? When you have a big emotion, you know, you have yourself less.” This surprised me, yet I recognized that feeling, and I said, “That’s what I feel.” Eli Siegel: “All right, but you still want to have a big emotion? You want to be swept by the external world?” “Yes,” I said, “I do.”

Mr. Siegel then showed me the one way I could “be swept by the world,” have big feelings and have myself more, not less, was in seeing that the world was not inimical to me, but really like me through the opposites. He showed that I was related to, among other things, two Renaissance painters, the classic novel Gulliver’s Travels, a woman from Westchester and one from Iran, flowers, music, and a Gothic cathedral and a person walking through it. The woman from Westchester was Barbara Buehler, whom I had begun to date and who was present at this lesson. Mr. Siegel asked me:

Can you be deeply affected by a person and be stronger? Do you think the depths of another person—woman or man—are so different from yours? As far as I know, when a woman is profound, she’s pretty much like a man who’s profound. Do you think that there are any profound women? Ms. Buehler, for example?

“Oh, yes!” I said. Soon I began experiencing the large emotions I had longed for, and I knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life with Barbara, and I married her. Today I love her more than ever—her perception, criticism, and encouragement.

Le Corbusier was also in a steep fight between coolness and warmth that troubled him throughout his life. He was born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret in La Chaux, a town in the Swiss Alps that was famous for its watches, and his parents were both watch engravers. (He later took on the name he is now widely known for, Le Corbusier, often shortened to Corbu.) His father, an expert mountain climber, took him on walks near their home in the Swiss Alps, where he loved to draw from nature. That time, he recalled,

was one of insatiable curiosity. I learned about flowers, both inside and out, the form and colour of birds….My master [said] Scrutinize in [nature] the cause, the form, the vital development and make the synthesis of it in creating [art].

Le Corbusier entered art school at the age of fourteen, and at seventeen executed his first house. With the money he earned, he traveled to Eastern Europe and the Mideast, filling 70 books with notes and sketches of sites and buildings he loved.

But with all he cared for, Le Corbusier also felt early that people were against him. One biographer, Charles Jencks, writes:

He continually spoke of the persecution of his ancestors, [Albigensians, originally from Southern France, who had been condemned as heretics by the Catholic Church for centuries].…Looking back in the 1940s…Le Corbusier said: “All my life people have tried to crush me.…Luckily I’ve always had an iron will.”

Little is written about Le Corbusier’s relationship with his parents, except that he was devoted to his mother, who encouraged his care for art, but also—it seems—his suspicion of people. Instead of being grateful for what he learned studying with two respected architects, he was cold, saying: “I am self-taught in everything.” Jencks writes that, using a pseudonym, Jeanneret wrote scathing attacks on other architects in the 1920s, “always changing the criticism to suit his ends.” “One has to be conceited,” he said, “swaggering, and never doubting—or at least not let it show.”

But no person can like himself for being cold and having contempt. As I will show, it made Le Corbusier cruel and terrifically unsure of himself.

2. The Fight between Coldness and Warmth Is Resolved in Art

“The greatest fact about coldness and warmth,” writes Ellen Reiss, Aesthetic Realism Chair of Education, is that

they are aesthetic opposites.…The authentic coolness we want, and which Aesthetic Realism enables a person to have, is the coolness of art: the coolness that is form, composition, order. This coolness does not come from contempt. It comes from seeing an object with such fullness of respect that one’s emotion has, inevitably, logic and control.

As I studied Le Corbusier’s work, I was affected to see that these opposites, so painfully divided in his life, are central in his architecture. Logic and control, which are on the side of coolness, are paramount in his Villa Savoye of 1929, where all rooms are enclosed in an almost-perfect one-story cube, elevated on columns laid out on a regular 3-meter-by-3-meter grid. Yet the house is warmly playful too.

The rooms are not formally arranged, but placed functionally around a lovely terrace which is carved out of the building cube, yet neatly contained within it. Corbusier, who, like me of once, likely felt having large feeling for people was messy, could have learned from the way the geometry of his house simultaneously controls and yields to the functions it encloses.

Yet even here in one of his best designs, Corbu’s coolness can be seen in how Villa Savoye, rather than joining gracefully with the meadow, hovers aloofly above it, gingerly touching the earth with those thin white columns or pilotis, which in later projects he made heavy and looming.

3. Why Are We Cold to The Person We Love?

At the age of 43 Le Corbusier married fashion model Yvonne Gallis, whom he described as “a highly spirited woman with a strong will, integrity, and tidiness.”

It seems she was a lively critic of her husband’s sometimes inflated sense of self-importance, and he was grateful for it. But Jencks gives instances of troubles in their marriage. In his book Self and World, Eli Siegel writes,

[I]t is easier to get to satisfaction of a kind by not seeing the tremendous and subtle and wonderful reality outside oneself in its completeness, its exactness, its tireless change. So we decide to get soothingness and power by not seeing it. And we have done this in love.…It has made for perceptible and obscure misery.

An example of Le Corbusier’s non-seeing of Yvonne, his coldness to her, was his feeling that he knew what was best for their home. Instead of wanting to know and learn from her, he imposed his will and there were many arguments. Yvonne complained that the glaring sunlight flooding her kitchen through a glass wall her husband designed was “driving me crazy.” Said Corbusier, “I absolutely fail to understand her.” But did he really hope to?

I think that, like many husbands then and now, Corbusier didn’t feel he had to know a woman. Instead, he felt he should be able to own and manage her. I know it makes for coldness and misery, for I regret this is what I did within months of marrying Barbara: I felt I knew best how to run our home, and didn’t think it was important to know what my wife felt. Then in an Aesthetic Realism class I learned about what was running me, enabling me to change and become kinder. Ms. Reiss asked: “Do you think you feel insulted that you care for Ms. Buehler as much as you do? And you’re not going to compound it by being interested in what goes on in her?” “Yes,” I said. And a little later she asked: “What is the thing you treasure most in yourself?”

Dale Laurin: My care for architecture.

Ellen Reiss: Do you think that would be helped or hurt by coldness to Barbara Buehler?…You should really give this a workout: Does how I see my wife have anything to do with how I see architecture?

And she asked me if I wanted to embrace Barbara and say, “I begin now to really try to know you, Barbara!” The answer was Yes! And I did so, which made for a big change. As I welcomed and liked learning from and being more affected by Barbara—her perception as a woman and a city planner—my preferences in design and my own work became less rigid, more warm and free.

4. Being Cold Makes Us Cruel

In 1929 Le Corbusier designed a shelter for the Salvation Army, Cité de Refuge, in Paris. His desire for plenty of sunlight and pioneering use of air conditioning show real warmth for people.

But when high costs meant fans had to be substituted for air conditioning, Corbusier ignored building codes and built the shelter as designed: with floor-to-ceiling windows that did not open, for that would alter the building’s appearance.

People seeking relief found stagnant air, and in the summer, unbearable heat. But he met criticism of his design with icy contempt, writing:

We have fifty-one rooms for mothers with babies….Because the old ladies…can’t stick their nose out of the window…they pretend they are suffocating….As a result, the Salvation Army wanted to play a dirty trick on me and put in some fifty windows on my facade, opening onto the outside…

“They don’t know at all what they’re talking about,” Le Corbusier wrote in another letter, “…they are obsessed by fixed ideas.…We have the obligation to ignore this and to pursue positive and scientific research with serenity.” I believe there is a direct relation between this brutal coldness and what Jencks writes, that with all the praise and awards he eventually received, Corbusier spoke with “lacerating self-hatred [calling himself] a rat, a person who had led a dog’s life,…a clown.”

He needed the self-knowledge and criticism of his contempt that people are fortunate to receive in Aesthetic Realism consultations, such as those my colleagues and I have been honored to give to Stanley Mead, a 36-year old architect from Ohio. In one consultation Mr. Mead said he was troubled by the way he felt separate from and resentful of people, including his partner and clients. We asked him, “How much do you want to be deeply affected by things? Do you think the great architects of the past are great because they were affected by things?” Stanley Mead: “Absolutely!” Consultants: “…or because they wanted to put a limit? Is there in you a desire to welcome the world and also a desire to limit that?” “Yes,” said Mr. Mead.

As his study continued, we gave Mr. Mead assignments to encourage deeper, more accurate thought and feeling about other things and people. For instance, to have him see his office partner Peter, who habitually angered him, more impersonally, widely, we asked him to write each day about one pair of opposites he saw in a work of architecture he liked and how those same opposites were in Peter. About “Individuality and Relation,” he wrote,

In a subway station…I saw these opposites in a brick arch. Each brick alone is visible, and together they create a structural form, the arch. Peter seeks solitude to study architecture, to read, or to sketch; and is related to others as he expresses his thoughts, as he laughs, listens, responds, and in doing so expresses an individuality I haven’t wanted to know very much.

Writing this Mr. Mead saw that he, too, was trying to put these same opposites together. And his re-seeing of the world, people and himself continued. A few months later he wrote, “My life has changed from one of scorn and isolation to being more and more affected by the world. I think consciously of the opposites now as I design, and this is bringing more substance and beauty to my work, thereby having a better effect on my clients.”

5. Art Has the Honest Warmth We Want

At the age of 63, Le Corbusier surprised many critics by designing a building that seemed so free, so warm, so different from anything he had done. This is true and it’s why I believe his pilgrimage chapel Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp in the French Alps is one of the great buildings of the 20th century.

Here, the indelible impression made by the Parthenon on Le Corbusier many years earlier inspired the architect’s most powerful, moving expression. Writes critic Richard Etlin,

There on an Acropolis-like site, Le Corbusier created a sculptural form with a diagonally tipped roof that rises majestically.…Pilgrims, ascending the hill by foot, are presented with the type of oblique view of the chapel comparable to the one [at the Acropolis].…This building…re-creates, albeit in its own manner, the sentiment of the sublime,…a house of worship for today’s world in the guise of his own modern Parthenon.

At Ronchamp, I think that Le Corbusier—deeply, if silently, ashamed of his coldness, particularly during the War—wanted to break out of his steely armor and be “swept by the external world.” He once commented, “I do not know the miracle of faith, but I often experience that of ineffable space, which is the highest level of artistic emotion.” Ronchamp is a beautiful oneness of space and matter, inside and out.

This building is not aloof from the earth, but rises organically from it, its swelling roof seeming to form the crest of the hill itself. We are compelled to walk around this chapel that seems lovingly sculpted by hand, moved by its concave forms which dip, rise, and culminate in that powerful sharp edge of wall that soars to the heavens.

Inside, we feel warmly enveloped within its thick walls and darker, swooping ceiling. But a narrow gap around the perimeter suffuses the ceiling with sunlight, making heaviness lighter, even ecstatic.

And most moving of all are the many large and small square openings that slice through the thick walls, welcoming in magnificent rays of warm colored light. I see this chapel as the fortress of Corbusier’s heart, which he hoped so much to be pierced, illuminated, completed by a world he could truly like. Aesthetic Realism has done this for me, making my life increasingly happy and proud, with sweeping emotions about the world I wouldn’t trade for anything. This education is the birthright of every person.