By Dorothy Koppelman

I learned that the only way to like the world honestly is to see it as a oneness of opposites; and further, that seeing it this way is the means to honestly liking yourself. The more I study this Aesthetic Realism principle stated by Eli Siegel, the more I am thrilled at its truth: “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.” *

The way Edward Hopper, in his great paintings of the city and its people, puts together the opposites of Separation and Togetherness is why I, like many others care for him so much. We can see our city and ourselves with new eyes as we see how opposites are here. These sentences from Eli Siegel’s Self and World are crucial in understanding the central impetus of the painter, and the work itself:

A person is separate from all other things and together with all other things. To understand opposites in a self, the meaning of together and separate must be seen. All art puts separateness and togetherness together. All selves want to do this.

Hopper, who lived from 1882 to 1967, was born in Nyack, on the Hudson River, but lived in New York City for most of his life. He painted the small towns, the country roads, the country stores, the early buildings, gas stations, cities of America, in such a way that he has come to symbolize the American feeling. He shows, in his forthright manner and yet exquisitely subtle compositions of people and things, that no matter how locked in, how shut off a person may seem, we are inevitably related to everything around us.

Hopper himself has been described as “immensely tall, immensely quiet, and utterly reserved.” He said he had a “propensity for solitude” since childhood. To have a “propensity for solitude” implies, as I well know, saying the world isn’t good enough for me. What Hopper grappled with as artist—the essential relation of shape, color, weight, light, the sameness and difference of people and things—he did not know how to use to be closer to people in his everyday life.

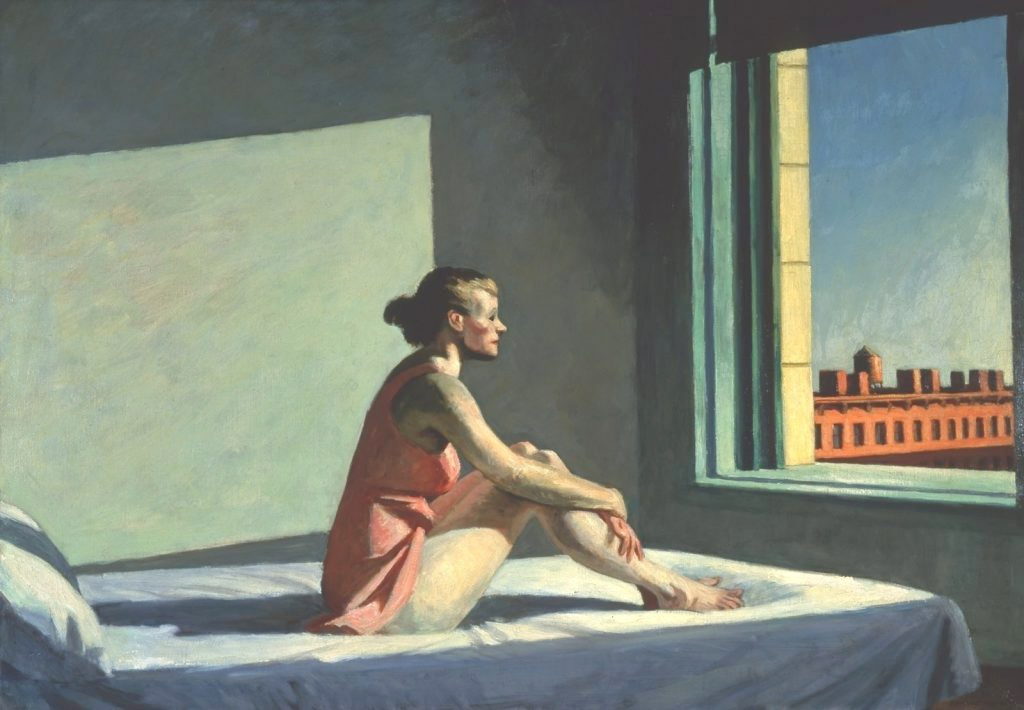

In Self and World Mr. Siegel describes the way a person is both separate and related; I think Hopper’s Morning Sun is a beautiful illustration of these words: “So we are alone in our blood and our bones and our thoughts. It seems we are separate, if we want to feel that way….And yet we can look out.”

Here, a person looks out a window while she folds her hands around her legs, and as she does so, the sun lights the white bed, her face, her body and the wall. The angle of her knees is echoed far in the distance by the pink water tower. And the color of the line of buildings is like that pink and so intimate slip she wears; the shape of the buildings continues the shape of the bed. The painter shows that even in great separateness and bareness there is a relation of clarity and softness, of angularity and lightness, of the bones inside our bodies and the buildings we live in.

Hardness and Softness, Silence and Talking

In 1971, after a major exhibition at the Whitney Museum and after the artist’s death, a critic wrote: “Hopper was undoubtedly America’s most tight-lipped master. Attempts to draw him out inevitably met with a prolonged, uncomfortable silence.” I think Hopper must have felt bad about his stony way of shutting people out. We can see his criticism of himself in his own work.

He famously said about his purpose: “All I wanted to do is paint sunlight on the side of a wall.” But I see, looking at this room with its geometric light [above, in Morning Sun], and in this gothic, formidably lonely building, [below, in House by the Railroad], an artist saying: I want to be warm to the world—to welcome the world into myself.

In an Aesthetic Realism talk titled Everything Has to Do with Hardness and Softness, Mr. Siegel spoke of the work which, although it has no people, no conversations, was once on every New York City phone book.

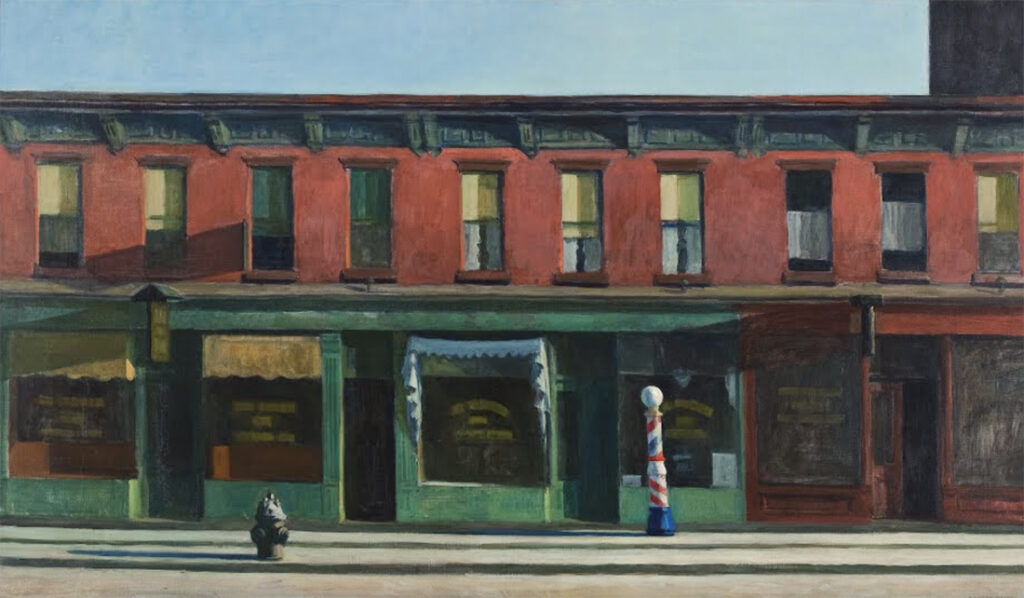

Calling Early Sunday Morning great, Mr. Siegel said:

The purpose was to present the stillness, the gently and deeply terrifying stillness of things along with something substantial, and here and there just attempting to be cheerful….The reds…are not so cheerful, but the sun is in them. Shadows…bring softness to everything. An object and its shadow are softness and hardness.

The way these hard brick buildings take the warm sun is a lesson in what makes for beauty and an urgent message: it is welcoming the world outside of oneself that makes us like ourselves.

Eli Siegel saw that Hopper had humor; he described these windows as: “two with the blinds down, three windows, then two somewhat darkened, with light in the last.” He said the artist was “mischievous and somnolent”; that “the unknownness of things and the seenness of things interplay.” That is just what we see: the darkened windows have curved and partly opened curtains, the awnings outside partly hide, are stiff and also curved. The tall barber pole with its red spiraling motion and the little fireplug are cheerful, they almost talk to one another.

Hardness and softness are in our bodies, our thoughts, and in what we see. I will never forget how, when I first heard Mr. Siegel speak, he put out his hand, opened it with its welcoming palm, then closed it in a fist, and said that just as these are aspects of one hand, and must work together to have a hand function beautifully, so our purpose in being hard and soft, gentle and tough, has to be the same.

In Office at Night, we see two people, so separate, so looking for something, so silent. Yet what we are looking at is a great double triangle relating them to each other and to the objects in their office. At the apex is the woman with all her blue curves pressed against a rectangle; she looks at a man whose body rises from the dark rectangle he looks down at, and then in the left corner the triangle is completed by a half-seen typewriter, in a cut-off triangle.

Edward Hopper, the painter, had an intense desire to compose the opposites he saw in things. I believe he wanted to study the desire to separate oneself as he felt it and as he saw it in people. We see this in a note called “Confidentially Yours,” about Office at Night: “My aim was to try to give the sense of an isolated and lonely office interior rather high in the air, with the office furniture that has a very definite meaning for me.” Then a clear rectangle of light—in keeping with Hopper’s “sunlight on a wall”—joins these silent, separate people.

The Opposites in Art Are Vividly Present in Marriage

When Hopper married at 42 the lively Jo Nivison, a fellow painter, they lived and worked in their studio on Washington Square. Lloyd Goodrich, formerly director of the Whitney Museum and biographer of the artist, writes that “there was bickering” between the Hoppers, and at the same time they were inseparable. And he describes this:

Hopper would explain some technical challenge [a] picture had involved, persistently avoiding all attempts to analyze its subject. Inevitably, Mrs. Hopper—who took a proprietary air toward her husband and his work that others found irritating—would interrupt the conversation, allowing Hopper to retreat into his usual silence.

On the other hand, Mrs. Hopper is recorded as saying: “Sometimes talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.”

The urgent message of art which Aesthetic Realism teaches is this: the only way we will like ourselves is to see and like the aesthetic oneness of opposites in the world and ourselves as an inextricable, living relation. Beauty itself, always and eternally “a oneness of opposites” is the great criticism of the separation of ourselves from the world; it is the opponent of the contempt that cripples people’s lives and makes for international horrors.

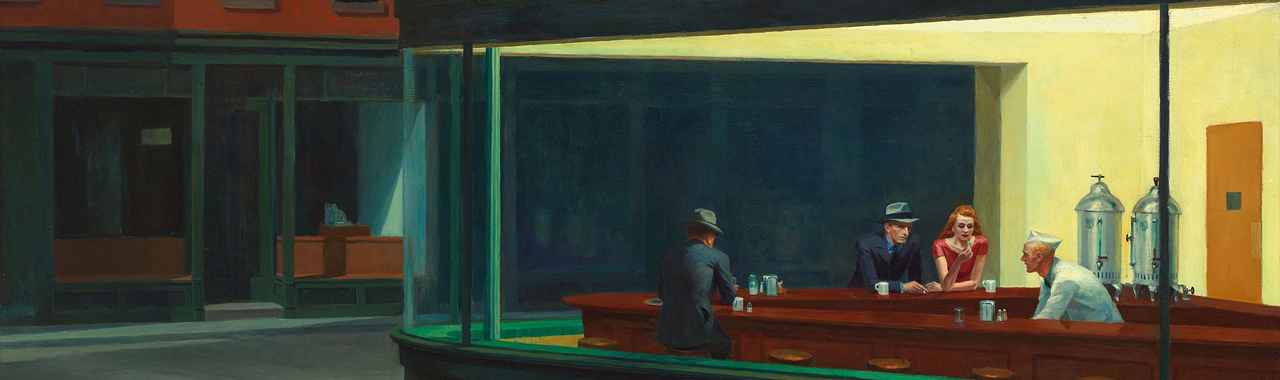

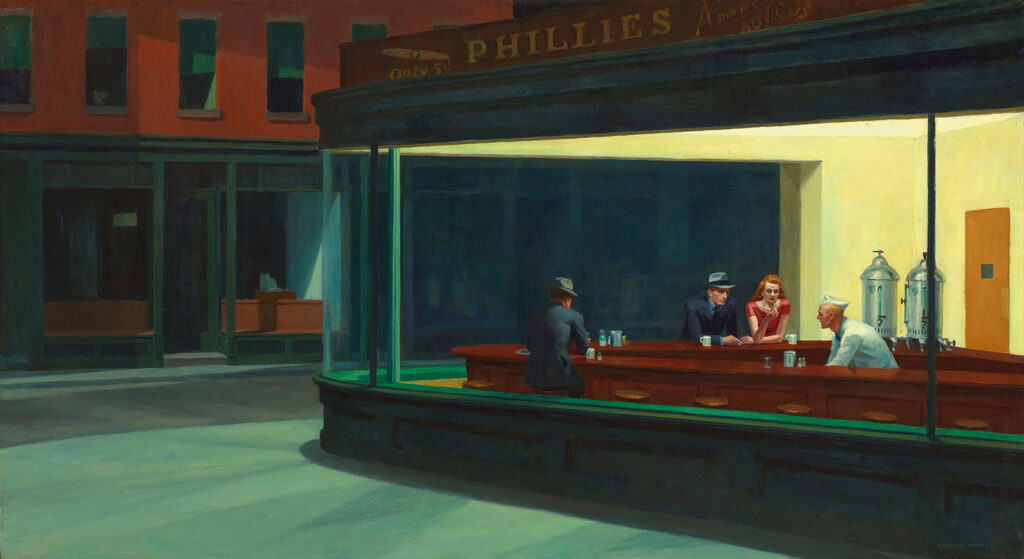

The famous Nighthawks shows what Hopper really wanted, and shows his awareness of that hardness and softness he saw in people and in himself perhaps. “The man [at the counter] is so solicitous,” Mr. Siegel had noted in his discussion of the painting, “while the others have hard looks.”

I see the whole painting as a criticism of separation through a deeply moving composition of separateness and togetherness, of hardness and softness. The hard glass window, through which we see these people in their curves and angles, touching and not touching, is miraculously painted so that it joins inside and outside; in its transparency it welcomes what Mr. Siegel described in Early Sunday Morning: “the unknownness of things and the seenness of things…”

In order to like ourselves, we have to do what all art and the paintings of Edward Hopper do—welcome and delight in seeing the relation of opposites in ourselves and the world.

♦ ♦ ♦

* To introduce the landmark Aesthetic Realism principle at the basis of this talk, we’re quoting a statement from Dorothy Koppelman’s “Jackson Pollock—and True & False Ambition: The Urgent Difference.”

This paper was part of a seminar at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation given by Aesthetic Realism Consultants and artists Dorothy Koppelman, Marcia Rackow, Chaim Koppelman and architect Dale Laurin.