By Dorothy Koppelman

I have learned from Aesthetic Realism how every woman wants to see and be seen from the time she opens her eyes as a baby; first—she wants to see the world as it is, because truly seen, the world has a structure which is beautiful. In Self and World Eli Siegel writes:

Aesthetic Realism, in keeping with its name, sees all reality, including the reality that is oneself, as an aesthetic oneness of opposites…

I learned that the only way a person can see the outside world as friendly is to see it wholly as it is, and the only way we can like ourselves is to see the aesthetic relation of the world and ourselves.

In Aesthetic Realism lessons I was seen by Eli Siegel, not as a disdainful critic, blasé at twenty, but as a woman yearning to like the way I saw the world around me. I have had the honor of being seen truly by Eli Siegel and I know that every woman wants to be seen this way—as having the opposites of reality itself. He asked me: “Are you the same person alone as you are with other people?” It had never occurred to me before that such a thing was possible. I learned that assertion and retreat, inside and outside were opposites in the world, and that I could see this in the objects I liked to paint—that it was this presence of opposites that made me want to paint. I wanted to see and to like myself and the world at the same time.

Learning this made my life coherent—that I wanted to see the world all the time in every situation, the way it is seen in the paintings I cared so much for.

This is Eli Siegel’s great principle of Aesthetic Realism: “All beauty is a making one of opposites and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in our lives.”

I believe this statement, embodying Aesthetic Realism, is the greatest seeing the world itself has come to. I have seen it to be true historically about all art, about my own work, and about people,

1. The Opposites in Every Woman’s Life

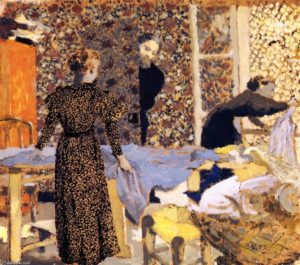

I am considering the work of Edouard Vuillard as a lesson in paint showing how deeply an artist has looked at women and their lives. The early paintings by Edouard Vuillard put together the opposites in every woman’s life—the intimate and the large, closeness and distance, thought and motion or energy and repose. Vuillard shows how the opposites, the structure of a timeless reality, are present in us and in a work-a-day world; I care for his work and have been affected by it very much. (click on image for larger size)

A woman wants to be seen in relation to all things, all the time. When, in an Aesthetic Realism class, Eli Siegel showed me the way opposites—beginning with the hardness and softness of the chair I sat in—were all around me, I said three words to myself I had never thought of before: “I am related, I am related, I am related!” My self took on a new dimension.

In the Fifteen Questions, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, those beginning opposites of reality are asked about by Eli Siegel—Sameness and Difference:

DOES every work of art show the kinship to be found in objects and all realities?—and at the same time the subtle and tremendous difference, the drama of otherness, that one can find among the things of the world?

In The Seamstress, Vuillard shows “the kinship to be found in objects and all realities.” Here is the plain, blue back of a woman who seems to be absorbed in herself as she is absorbed in her sewing. But the artist sees the act of sewing as an act of relation.The materials on either side of the seamstress share her soft shape; under her arm is a white triangle, and to her right, a blue one. The slim, straight lines of the chair on which she sits are the same color as her hair, the same as that mysterious vertical column which connects her head to that pink and red triangle, like a meditative and lively cap.

Andrew Ritchie, in his 1954 book on the artist says:

[Vuillard] presents the quiet, ordinary relationships of the animate and inanimate, the fusion of person and thing until both become one, and every shape, every color, every accent merges into sustained, tapestry-like rhythms.

The rhythm of relation, of sameness and difference is here in, for instance, the way the seamstress’s neck is painted with the same thick strokes of a light color, the same shape as the rectangular boxes to her right and to her left. Vuillard, in his work, puts together the opposites every woman wants to see as one every day, every morning—the near and far, the everyday and the strange, the familiar and mysterious.

Vuillard, who lived from 1868 to 1940, was a Symbolist; affected by the poet, Mallarmé, he went after “nuance,” suggestiveness, and what the poet called “atmosphere.” In one passage of the Journals he kept for over 40 years, recording what he saw, Vuillard wrote:

This morning, upon awakening I was looking at the different objects that surrounded me…the curtains, the chair, the paper on the wall…the knobs of the open door, glass and copper, the differences of perspective through the two windows….I feel pleased to try and understand the character of objects…to thus understand the world was…I believe, the goal…to find grand emotions….And then…I was astonished to see Maman enter in a …peignoir with …stripes…There was a vivid atmosphere…a living person…

In painting after painting, on small pieces of brown cardboard, using thick paint and layers of theatrical glue used in stage sets, Vuillard showed that in the crowded rooms, the routine domestic activities, there is the romance of the wide, mysterious world: opposites as one.

In Woman Sweeping, for instance, one soft color brown pervades the room, showing subtle changes as it mingles with shadows, and defines the ever-present bureau, the light open door, even the sweet, round cap of Madame Vuillard. But she is not sweeping everything away so she can forget things. That slim, diagonal broom is the means of relation between her round body in its striped gown and that bulky form with its patterned surface, rising so mysteriously right in the foreground of the room. It is that weighty shape, like a nucleus, which allows the objects of this room to go out, spread beyond the edges of the canvas.

I love teaching with my colleagues in Aesthetic Realism consultations what we have learned about the only antidote to that boredom, irritation and loneliness which arise from the idea that we have to separate what goes on inside our homes from all that goes on in the outside world. The only opponent to that kind of contempt is to see the vivid presence of the opposites—beauty itself—in everything that exists.

Often, when a woman is cleaning, two things occur—feverish activity and then exhaustion. Is there, however, in this painting, a relation of impediment and ease, which makes for serenity and, as Eli Siegel described, there must be in all art, a sense of stir?—Do we see here the oneness of opposites we want in our lives?

Does the fact that so many objects and shapes beyond the edges of this room suggest that the sweeping woman has a relation to a wider space, a world beyond that cozy room?

I am sure that every woman wants to be asked as Mr. Siegel asked me: “Is a person’s business the whole world, or snug warmth?—Do you want to be in relation to all space or just in a cupboard with a heater?” I see Vuillard’s painting as not only an affirmation of relation but a criticism of the desire in a woman, or any person, to sweep things out of sight. Vuillard, as he showed in his painterly perception the shapes and colors of relation, also criticized visually the notion of separation in one’s life.

II. What Women Want Is the Aesthetic Criticism of Self

The most dramatic, romantic and important thing that can happen in a woman’s life—has happened in mine and continues to happen—is to learn how to see the difference between contempt and its selfish pleasures and the true criticism which is the same as respect, the same as love, the same as art.

Eli Siegel was the first to see and to say that all art has the criticism we need in order to like the way we see the world. In his essay, now published in The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, “Art As Criticism,” he writes:

To see is to criticize….The world cannot be seen as good until it is criticized; and art is the criticism and through criticism, the loving acceptance of the world.

Edouard Vuillard’s The Blue Sleeve exemplifies that “criticism” which is the “loving acceptance of the world.” It is a study in contempt, anger, the accompanying limpness and the grand opposition to those feelings which exist in our very selves and in the structure of things.

The scowling woman asserts anger, but the artist asserts a counter-offensive in that very bright blue arm. The girl’s hand, so large, so limp, rests however, on a rising triangle of light which leads quietly back to another figure, almost indistinguishable but serenely there in the background. Because Vuillard was a master at bringing distant depths to the surface, we feel this person is inextricable—like our whole selves—from the sidewise view of the unseeing girl. This woman, so brightly in the center of the painting, is simultaneously held in the girl’s curving arm, while her head and hair merge with the multi-colored, spreading world behind her.

“The world cannot be seen as good until it is criticized,” said Eli Siegel, and that is what Vuillard does here: The dark, almost religious arches of that chair in front support the worship of contempt and anger; the artist changes them in depth to the light, vertical and horizontal divisions of the spreading wall; and light and dark have changed places on the two faces. The angry division of light and dark, with its scowl, has been reversed so that we see an open eye in bright light and a most pleasing vivid, and yet symmetrical relation of light and shadow.

In Aesthetic Realism consultations women learn to see that even when we are asserting anger or scorn for the outside world, there is another, wider aspect of ourselves—no matter how hidden or submerged—which wants to be pleased rightly by the wide world.

In “Art As Criticism,” Eli Siegel writes:

In art, what the eye and self do is for the honor and full truth of reality; in what isn’t art, the eye can change reality out of fear, and in a manner dishonoring it.

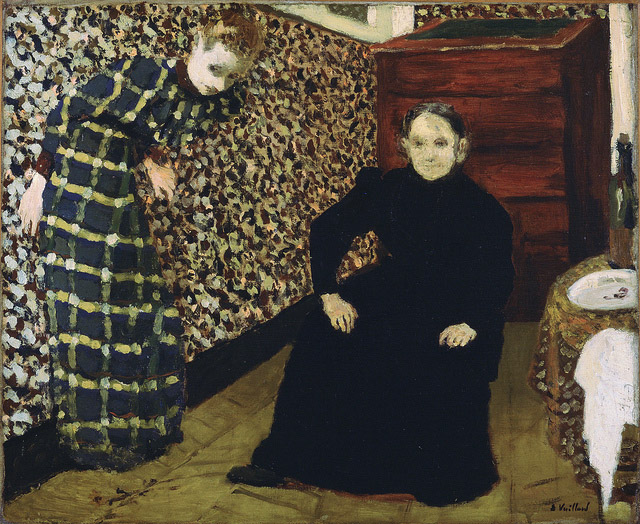

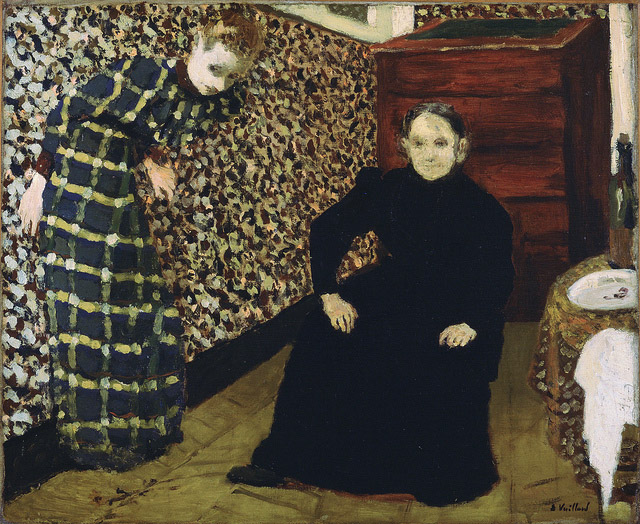

Interior: Mother and Sister of the Artist of 1893 is perhaps Vuillard’s most courageous and powerful painting. There is such a perception of evil in close quarters, and such a stunning aesthetic opposition. This is the desire in a woman to be unseen—the triumph of contempt in a woman—presented and masterfully opposed. In the deep perspective of this room, the young lady retreats, backs into and almost succeeds in merging with the patterned wall. She is fearful, suspicious and she emerges slyly above the central, implacable black form of the thickly masked, unseeing woman—her mother.

Eyes and selves here have “dishonored reality,” as Eli Siegel described. But the artist’s eye criticizes as we must criticize ourselves. The wall, as wall, will not allow retreat and it welcomes otherness in its active surface. The dark mother is center stage; blackness asserted is lightened, less frightening. And she is surrounded by the friendly red warmth of that bureau with its many drawers. The speed of the straight black bar at the base of the wall lessens the distance between these women and joins them just as surely as the light color of their four hands. I learned from Aesthetic Realism that objects are ethical because they put opposites together. The bottle, tall and curved, attached to the white, round plate, the cloth, soft and sharp, all say, as Eli Siegel said to me, “There’s something to be seen around here.”

Aesthetic Realism teaches this: “The seeing of a person or an object should contribute to your seeing the universe as it really is.” I am immensely proud and grateful to be able to study that way of seeing, to have learned more from the paintings of Vuillard and the writing of this paper, and to be a means of having the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel seen truly by all the persons of the world.